Long-Term Unemployment and the Great Recession

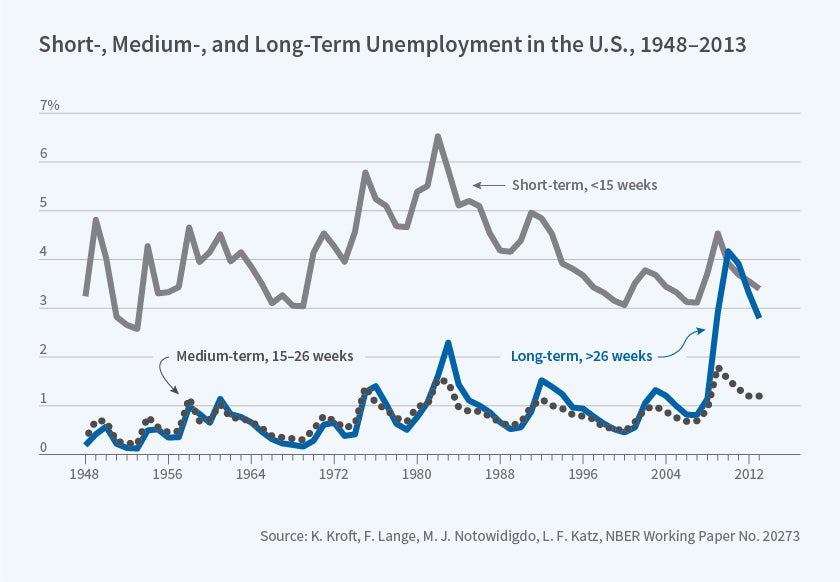

The share of unemployed individuals who are "long-term unemployed" — that is, unemployed for 26 weeks or longer — surged to record highs in the United States during the Great Recession. Figure 1 decomposes the overall unemployment rate into three groups — short-, medium-, and long-term unemployed — and shows the unusual trend in long-term unemployment during the Great Recession and its aftermath. For more than 50 years, unemployed individuals were mostly short-term unemployed, even during recessions. But starting in 2007, the long-term unemployment share increased from roughly 20 percent to 45 percent and remained at that elevated level for several years, even as the overall unemployment rate started to return to normal.

In our recent research on long-term unemployment, we have sought to understand the relative importance of the changing composition of the pool of unemployed individuals over time, the impact of "duration dependence" — the possibility that the chance of finding a job depends in part on how long an individual has been unemployed — and labor market nonparticipation in long-term unemployment trends in both the United States and Canada. In addition, we have also studied the role of long-term unemployment in recent changes in macroeconomic relationships, most notably the outward shift in the Beveridge curve — the relationship between the unemployment rate and the job vacancy rate — that occurred during the Great Recession.

The Negligible Role of Composition

In work with Lawrence Katz, we study the role of shifts in the composition of the unemployed in accounting for the rise in long-term unemployment.1 Intuitively, if unemployment during the Great Recession was concentrated among individuals who historically had been those most likely to end up in long-term unemployment, then some of the increase in the long-term unemployment share could be accounted for by compositional shifts.

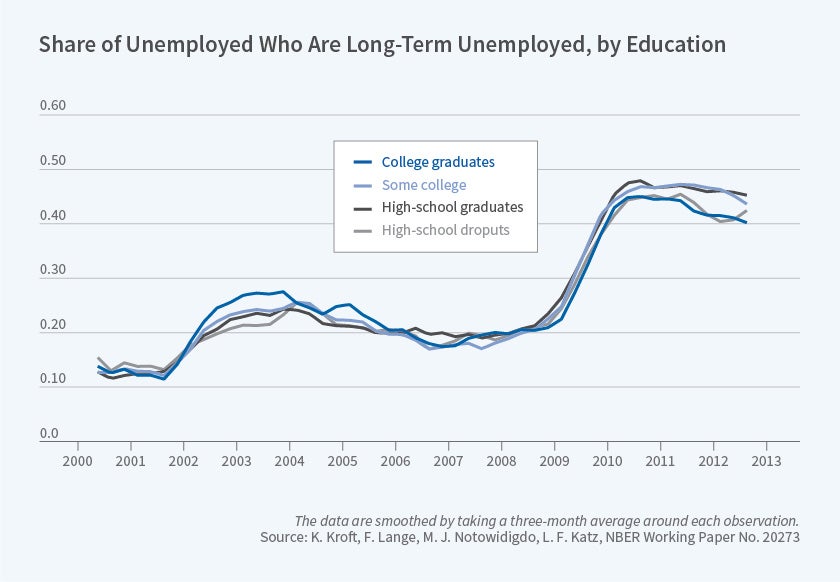

Using data from the Current Population Survey (CPS), we find no evidence that observable changes in the demography of unemployed people played a meaningful role in the rise of long-term unemployment. Instead, we find that long-term unemployment increased for virtually all demographic groups. For example, Figure 2 shows that the increase in the long-term unemployment share is fairly similar across all education groups. We find similar trends for many other groups defined by other characteristics such as age, occupation, industry, and geographic region. Change in the composition of the unemployed along observable criteria account for very little of the increase in long-term unemployment during the Great Recession, suggesting that changes in composition along unobservables are also unlikely to explain the increase in long-term unemployment.

Duration Dependence

In our research with Katz, we also study the role of negative duration dependence in understanding long-term unemployment. Negative duration dependence refers to the tendency of the job-finding rate of unemployed individuals to decline with the duration of unemployment. This is a plausible explanation for some of the rise in long-term unemployment, since duration dependence can "produce a self-perpetuating cycle wherein protracted spells of unemployment heighten employers' reluctance to hire those individuals, which in turn leads to even longer spells of joblessness."2

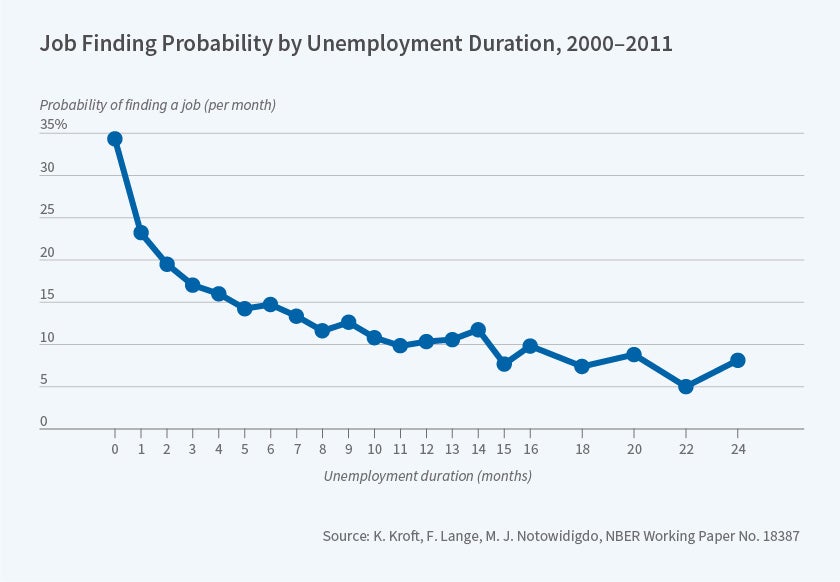

In CPS data, we find negative duration dependence in the average job-finding rate.3 That rate falls sharply with the length of the unemployment spell, particularly during the first few months, as shown in Figure 3. A key issue with interpreting this pattern, however, is that it may conflate unobserved heterogeneity with "true" duration dependence. In particular, the average job-finding rate may decline with duration because unemployed individuals have heterogeneous, latent job-finding probabilities; in this setting, the surviving unemployment pool becomes negatively selected over time. If negative selection occurs, then those who are unemployed longer will, on average, have lower job-finding rates than those who experience shorter unemployment spells. Alternatively, the job-finding rate may be lower for those with longer unemployment spells due to true duration dependence, which captures the idea that a given individual's job-finding rate declines with duration. This can be due to human capital depreciation, which makes workers less attractive to potential employers, or it can be due to statistical discrimination, as employers infer that those with long-term unemployment are likely to be lower-skilled than those who have been unemployed for less time.

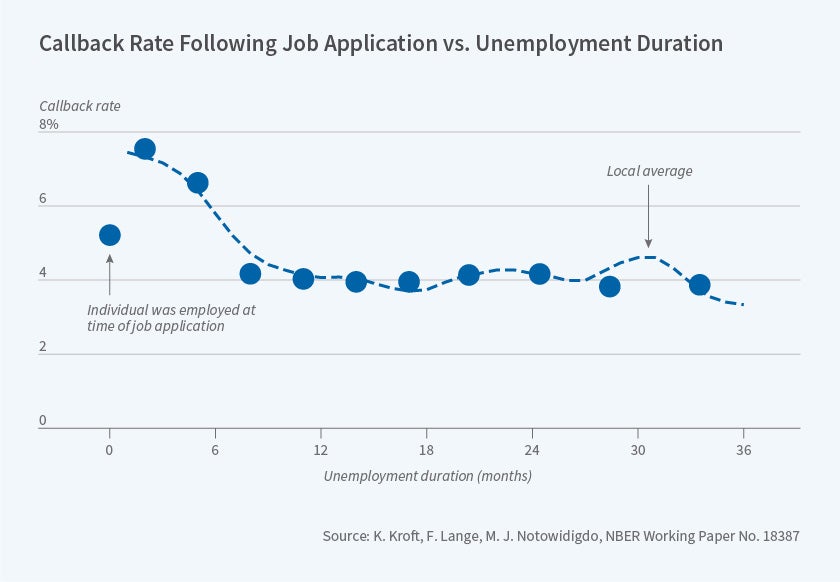

Several recent studies provide compelling evidence of true duration dependence using quasi-experimental approaches, such as longer durations of non-employment arising from delays in processing applications for Social Security Disability Insurance, and longer unemployment durations arising from a sharp age discontinuity in unemployment insurance eligibility in Germany.4,5 Our own research on duration dependence comes from a résumé audit study that randomizes unemployment durations on fictitious job applications. We find clear evidence of duration dependence in callback rates, as shown in Figure 4. Gregor Jarosch and Laura Pilossoph use a structural model to show that duration dependence in callback rates does not necessarily imply duration dependence in job-finding rates.6 As a result, the magnitude of true duration dependence remains somewhat uncertain, even though employers may engage in a substantial amount of statistical discrimination against the long-term unemployed. On balance, this body of research suggests that at least some of the drop in job-finding rates as unemployment spells lengthen is due to the causal effect of unemployment duration on the probability of finding a job.

Given this evidence, we calibrate a matching model of the labor market that allows for true duration dependence in the job-finding probability for the unemployed as well as transitions between employment, unemployment, and nonparticipation. For different but plausible degrees of duration dependence, this model can account for a meaningful share of the post-2007 rise in long-term unemployment.

The Role of Individuals Not in the Labor Force

The final explanation that we consider for rising long-term unemployment is transitions in and out of the labor force. Our rationale for exploring the role of nonparticipation (i.e., some individuals' decisions to leave or stay out of the labor force) builds on a prior large literature that emphasizes the fluid boundary between unemployment and nonparticipation. 7 8 9 Another motivation for this analysis is that the long-term unemployed are more likely to leave the labor force than to find a job.

When we add nonparticipants to the pool of job seekers, our calibrated model is much more successful in predicting long-term unemployment trends. In particular, ignoring the nonparticipation margin leads our model to under-predict both unemployment overall and the rise in long-term unemployment during and after the Great Recession. The combination of duration dependence and transitions in and out of the labor force can also account for a meaningful share of the outward shift in the Beveridge curve after 2008. Alan B. Krueger, Judd Cramer, and David Cho build on our matching model and reach similar conclusions.10

Comparing the United States and Canada

In work with Matthew Tudball we extend our matching model, calibrated to the US economy, to study the slightly less pronounced increase in long-term unemployment in Canada.11 We use restricted-use data from the Canadian Labour Force Survey (LFS). Unlike the CPS, the LFS measures "time since last job" for both unemployed workers and those out of the labor force. This allows us to study a broader measure of long-term joblessness that includes both the unemployed and nonparticipants. Using this dataset, we are able to enrich our model to allow for duration dependence in job-finding rates among both unemployed individuals and nonparticipants, and for flows between unemployment and nonparticipation. We find, as in our US analysis, that the increase in long-term unemployment occurred across demographic groups, and that there was a very limited role for composition in accounting for its rise in Canada.

In addition to Canada's less pronounced increase in long-term unemployment during the Great Recession, we also document another interesting US-Canada difference: There is no "outward shift" of the Beveridge curve in Canada. To document this, we construct a new vacancy series building on recent work by Camille Landais, Pascal Michaillat, and Emmanuel Saez that proxies for vacancies using a "recruiter-producer ratio" computed using the number of workers in "recruiting industries."12 We must use this approach because Canada does not have a monthly vacancy series that spans the last two decades.

Allowing for duration dependence, we calibrate our extended matching model using an approach similar to that in our work with Katz. Allowing for duration dependence in joblessness for all flows involving nonparticipants helps account for the rise in long-term unemployment in Canada.

Next Steps

Duration dependence continues to be an active area of research. Fernando E. Alvarez, Katarína Borovičková, and Robert Shimer develop new econometric tools for identifying true duration dependence, while Katharine Abraham, John Haltiwanger, Kristin Sandusky, and James Spletzer provide new evidence of "true" duration dependence by merging CPS data with several years of administrative wage records. 13 Additionally, several recent papers have complemented our own résumé audit study with additional audit studies of "employer-driven" duration dependence. 14 15 16

While most of the recent audit studies find some discrimination against the long-term unemployed, the magnitudes vary. One finding in our résumé study that seems surprising is that employers were more likely to call back newly unemployed workers, compared to workers who were currently employed. This finding is replicated in the recent résumé audit study by Henry S. Farber, Dan Silverman, and Till von Wachter.17 One explanation for this finding, based on our informal discussions with human resources professionals, is that "some employers express the concern that workers who are currently employed are not serious job seekers and, as a result, some employers are less likely to invite them for an interview."18

Our research has emphasized the role of duration dependence and transitions in and out of the labor force in accounting for long-term unemployment trends and the outward shift in the Beveridge curve. In our research in the United States, we have mostly used data from the CPS, which is well suited to studying labor market transitions between employment, unemployment, and nonparticipation. However, in order to use the CPS data in our model calibration, we had to deal with a number of irregularities and inconsistencies. For example, there are some disparities between estimates of flows between labor market states and estimates of changes in stocks over time. Recent research by Hie Joo Ahn and James D. Hamilton makes substantial progress toward trying to reconcile these and other irregularities in a unified framework, which should be useful for future matching model calibrations like ours.19

Lastly, our work in Canada gave us an appreciation for some of the key advantages of the Canadian LFS data relative to the CPS. Our paper and the work by Marianna Kudlyak and Lange suggest that durations of joblessness and unemployment are distinct economic phenomena.20 Researchers interpreting the duration of unemployment as the time since an unemployed individual was last employed will often be mistaken. The CPS could consider following the LFS in collecting time-since-last-employment data for both the unemployed and nonparticipants, particularly given the increasing interest in studying trends in labor force participation.21

This summary of our research on long-term unemployment is dedicated to Alan Krueger, who was working on long-term unemployment alongside us in recent years. He discussed much of the research highlighted in this summary during his 2015 Martin Feldstein Lecture at the NBER Summer Institute. We are grateful for his encouragement and feedback. His example continues to inspire us to study labor economics.

Endnotes

"Long-Term Unemployment and the Great Recession: The Role of Composition, Duration, Dependence, and Non-Participation," Kroft K, Notowidigdo M, Katz L. NBER Working Paper 20273, July 2014.

"Understanding and Responding to Persistently High Unemployment," Congressional Budget Office study, February 2012.

"Duration Dependence and Labor Market Conditions: Theory and Evidence from a Field Experiment," Kroft K, Lange F, Notowidigdo M. NBER Working Paper 18387, September 2012.

"Does Delay Cause Decay? The Effect of Administrative Decision Time on the Labor Force Participation and Earnings of Disability Applicants," Autor D, Maestas N, Mullen K, Strand A. NBER Working Paper 20840, January 2015.

"The Causal Effect of Unemployment Duration on Wages: Evidence from Unemployment Insurance Extensions," Schmieder J, Von Wachter T, Bender S. NBER Working Paper 19772, December 2013.

"Statistical Discrimination and Duration Dependence in the Job Finding Rate," Jarosch G, Pilossoph L. NBER Working Paper 24200, January 2018.

"Labor Market Dynamics and Unemployment: A Reconsideration," Clark K, Summers L, Holt C, Hall R, Baily N, Clark K. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 1979(1), pp. 13–72.

"A Comparative Analysis of Unemployment in Canada and the United States," Card D, Riddell W. In Small Differences That Matter: Labor Markets and Income Maintenance in Canada and the United States, Card D, Freeman R, editors, pp. 149–190. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993.

"The Measurement of Unemployment: An Empirical Approach," Jones S, Riddell W. Econometrica, 67(1), December 2003, pp. 147–162.

"Are the Long-Term Unemployed on the Margins of the Labor Market?" Krueger A, Cramer J, Cho D. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 45(1), Spring 2014, pp. 229–280.

"Long Time Out: Unemployment and Joblessness in Canada and the United States," Kroft K, Lange F, Notowidigdo M, Tudball M. NBER Working Paper 25236, November 2018.

"A Macroeconomic Theory of Optimal Unemployment Insurance," Landais C, Michaillat P, Saez E. NBER Working Paper 16526, November 2010.

"Decomposing Duration Dependence in a Stopping Time Model," Alvarez F, Borovičková K, Shimer R. NBER Working Paper 22188, April 2016. "The Consequences of Long-Term Unemployment: Evidence from Linked Survey and Administrative Data," Abraham K, Haltiwanger J, Sandusky K, Spletzer J, NBER Working Paper 22665.

"Factors Determining Callbacks to Job Applications by the Unemployed: An Audit Study," Farber H, Silverman D, Von Wachter T. NBER Working Paper 21689, October 2015.

"Whom Do Employers Want? The Role of Recent Employment and Unemployment Status and Age," Farber H, Herbst C, Silverman D, Von Wachter T. NBER Working Paper 24605, May 2018.

"Do Employers Use Unemployment as a Sorting Criterion When Hiring? Evidence from a Field Experiment," Eriksson S, Rooth D. American Economic Review, 104(3), March 2014, pp. 1014–1039.

"Measuring Labor-Force Participation and the Incidence and Duration of Unemployment," Ahn H, Hamilton J. Finance and Economics Discussion Series 2019-035, May 2019. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

"Measuring Heterogeneity in Job Finding Rates among the Non-Employed Using Labor Force Status Histories," Kudlyak M, Lange F. Working Paper 2017-20, Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco.

"Explaining the Decline in the U.S. Employment-to-Population Ratio: A Review of the Evidence," Abraham K, Kearney M. NBER Working Paper 24333, February 2018.