Bankruptcy Reform of 2005 Sharply Reduced Filings

Means testing, income limits, higher fees, and more paperwork for bankruptcy filings all contributed to the decline, especially among lower-income households.

Responding to a five-fold increase in consumer bankruptcy filings — from 0.3 percent of households annually in the early 1980s to 1.5 percent in the early 2000s — Congress in 2005 adopted measures to make filing for bankruptcy more difficult, more expensive and less financially advantageous for households.

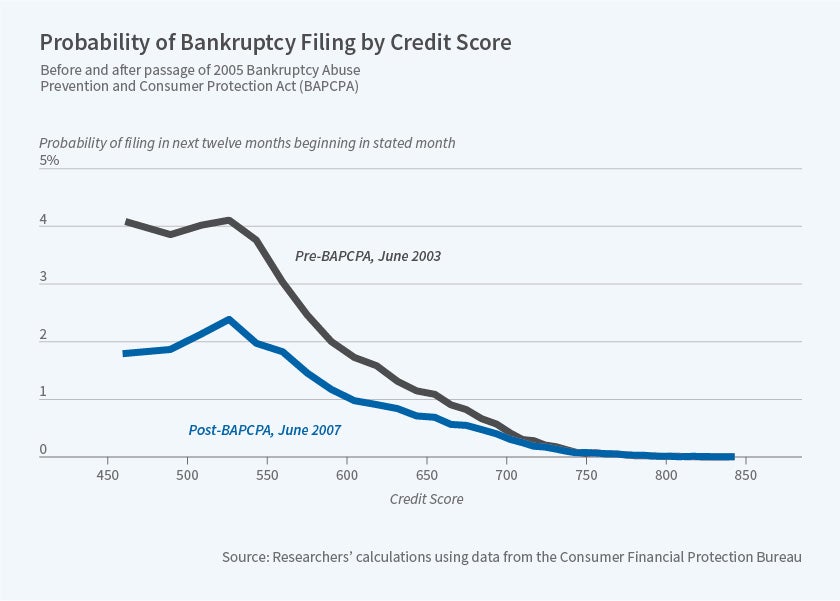

The Bankruptcy Abuse Prevention and Consumer Protection Act (BAPCPA) halved the rate of household bankruptcy filings according to The Economic Consequences of Bankruptcy Reform (NBER Working Paper 26254), by Tal Gross, Raymond Kluender, Feng Liu, Matthew J. Notowidigdo, and Jialan Wang. The study compares bankruptcy activity in the two years before and after implementation of the reform.

The new law imposed a means test that limited the set of households that could qualify for Chapter 7 protection under the bankruptcy code. Chapter 7 is the most generous for filers, allowing them to erase their debts. To be eligible for Chapter 7 filing after the reform, a household's income adjusted for family size could not exceed the state median for the six months prior to filing. This provision was intended to prevent more-affluent filers from abusing the system. Those who were no longer eligible for Chapter 7 could still file under Chapter 13. However, while prior to BAPCPA filers could propose their own repayment plans under Chapter 13, the new law required that they forfeit all of their disposable income for five years to pay down their debts. Other provisions of the reform resulted in higher filing and attorney fees and additional paperwork for filers. Filers were also required to enroll in financial education courses.

To study the impact of the law, the researchers analyze data on more than 3 million bankruptcies, accounting for 86 percent of all filings in the period 2004 through 2007. They conclude their analysis before the onset of the Great Recession in 2008, and they adjust for the last-minute rush to file before the new law took effect. They estimate that in the two years following BAPCPA's passage, bankruptcy filings declined by more than a million. The decline was more precipitous among Chapter 7 filings, as a result of the new means test.

The researchers point out that, for some households, the ability to declare bankruptcy operates as a form of insurance against large and unforeseen expenses. They illustrate this point by examining bankruptcies associated with medical expenditures. Using data on uninsured Californians who were hospitalized between 2003 and 2007, the researchers show that the likelihood of a bankruptcy filing following an uninsured hospital stay was 70 percent lower after reforms took effect. "[T]o the degree that uninsured health shocks can be generalized to other types of uninsured shocks, these results suggest that the reform meaningfully reduced the insurance value of bankruptcy," the researchers write.

To assess the impact of bankruptcy reform on interest rates, the study focused on credit card debt, since credit cards are the form of borrowing most likely to be discharged through bankruptcy. For each percentage point decline in the bankruptcy rate within a credit-score segment, the average interest rate declined by 67 basis points. This implies that credit card companies passed through to consumers between 60 and 75 percent of their savings from the reduction in bankruptcy write-offs that came about due to the reform.

In the wake of BAPCPA, bankruptcies of subprime borrowers fell especially quickly. In part as a result, subprime borrowers enjoyed a larger drop in interest rates than higher-rated borrowers did. This closed the gap between the interest rates charged to subprime customers and those charged to prime customers by about 10 percent.

— Steve Maas