Revenue Redistribution in Big-Time College Sports

Football and basketball, which attract many players from lower-income backgrounds, subsidize money-losing sports which are often played by more affluent athletes.

Strict limitations on player compensation in revenue-generating college sports such as men’s football and basketball result in a transfer of resources away from student-athletes in those sports, who are more likely to be from lower-income households, to those in other sports. The student-athletes in the sports receiving subsidies are more likely to be from affluent backgrounds, according to research reported in Who Profits from Amateurism? Rent-Sharing in Modern College Sports (NBER Working Paper 27734).

Craig Garthwaite, Jordan Keener, Matthew J. Notowidigdo, and Nicole F. Ozminkowski examine the socioeconomic impact of collegiate rules that restrict player compensation to scholarships and living expenses. They find that the college football and basketball players who are seen on network television capture less than 7 percent of the revenues they generate. Their professional counterparts receive about 50 percent of the revenues from their sports.

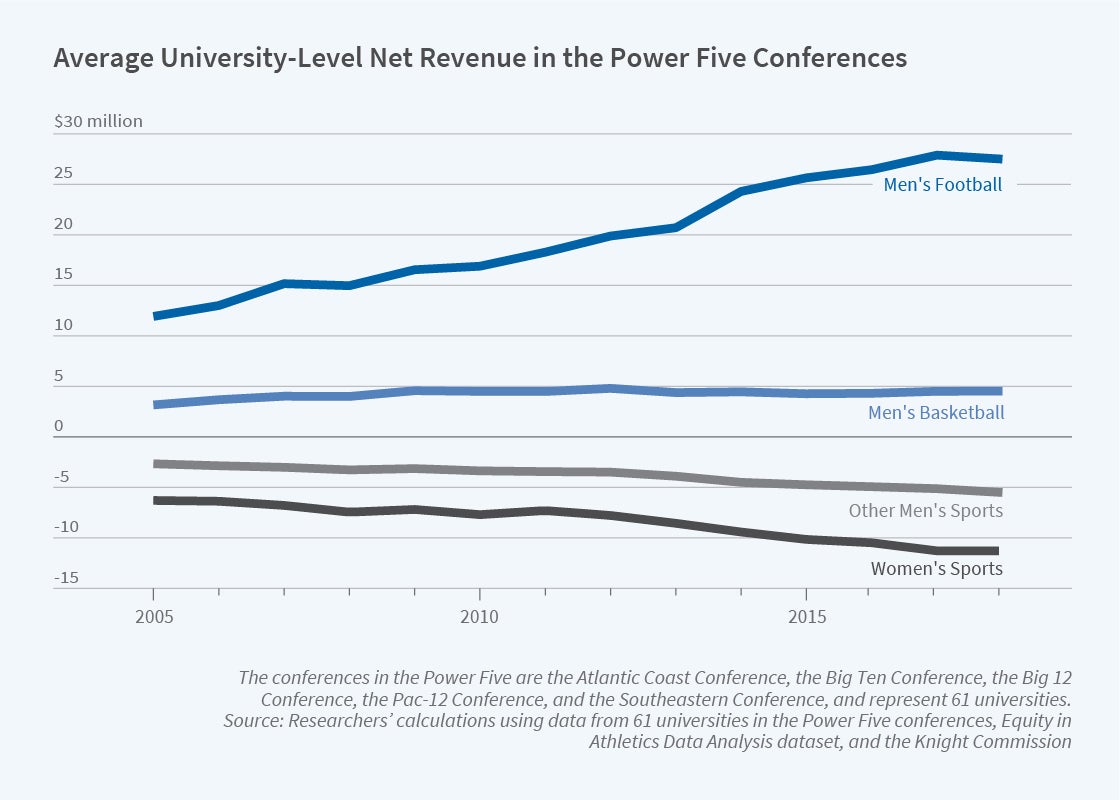

By compensating college players at levels below what they could command in an unfettered market, athletic departments realize economic rents that are used to subsidize non-revenue-generating sports — other sports that would otherwise earn negative net income — to pay the salaries of coaches and other administrative personnel, and to build sports facilities.

The study focuses on schools where most athletic department revenue is generated by ticket sales, media contracts, and promotional deals, primarily from football and basketball. The 65 universities analyzed are members of the Power Five conferences: the Big Ten, Pac-12, Big 12, Southeastern, and Atlantic Coast conferences. More detailed budget breakdowns were available from the 46 public institutions in the sample, but not from sports powerhouse private universities such as Notre Dame and Stanford.

Based on data from the public universities, average revenue for the athletic departments stood at $125 million in 2018, up 60 percent from a decade earlier. The surge in proceeds from football and basketball more than offset a 71 percent increase in the losses incurred by non-revenue-generating sports such as men’s golf and baseball and women’s basketball, soccer, and tennis.

The researchers report stark demographic differences between players in revenue-producing sports and other student-athletes in Power Five athletic programs. Black players account for nearly half the football and basketball players, but only 11 percent of the players in money-losing sports. Revenue-sport athletes attended high schools with a median family income of $58,400; players in other sports came from high schools with a median family income of $80,000. The researchers also note that only 12 percent of the men’s coaches, 9 percent of the women’s coaches, and 16 percent of the athletic directors were Black.

Between 2008 to 2018, when support for athletes rose by 47 percent, the average salaries of Power Five football coaches at public universities more than doubled, and those for coaches of other sports increased by 70 percent.

What if college players were paid? The researchers estimate a wage structure based on collective bargaining agreements in professional sports. They calculate that salaries would range from $2.4 million for starting quarterbacks to $140,000 for backup running backs. Starting basketball players, whose professional pay tends to be more uniform, would make between $800,000 and $1.2 million. The researchers caution that these values may be overestimated, since in the absence of labor unions, such as those representing professional players, the college athletes would likely command lower salaries, and the student-athletes’ pay might also be depressed if their loss of amateur standing reduced fan interest in college competition.

The researchers say the business model of the Power Five athletic departments resembles that of commercial enterprises, with one big difference: “While rent-sharing is theoretically possible in any commercial venture, the potential for rent-sharing in college sports is particularly great because of the NCAA rules limiting the amount of compensation athletes can earn.”

— Steve Maas