If There's a Doctor in the Family, Health Outcomes Improve

A study using Swedish data finds that individuals in families that include a health professional are more likely to engage in preventive health care, live longer, and are less likely to suffer from chronic conditions.

There is a large and rising gap between life expectancy for high- and low-income individuals in the United States. For men born in 1930, for example, life expectancy at age 50 for those in the top fifth of the income distribution is more than five years longer than for those in the bottom fifth. Many factors — including lifestyle, differential access to insurance, and quality of medical care — may contribute to this gap.

In The Roots of Health Inequality and the Value of Intra-Family Expertise (NBER Working Paper No. 25618), Yiqun Chen, Petra Persson, and Maria Polyakova explore another explanation: how access to medical expertise affects health. They study how health outcomes in Sweden are affected by whether a person has a family member who is a doctor or other medical professional. On average, individuals with doctors as relatives live longer and are more likely to engage preventive health care services.

Sweden's rich data infrastructure allows the researchers to map family trees and to track longevity as well as experiences with medical care. Despite a universal health care system that equalizes formal access to care, there are substantial differences in health outcomes across income groups. This finding leads the researchers to search for factors other than access to care that might explain the socioeco-nomic gradient in health status. They focus on access to health knowledge, which they proxy by the presence of a health professional in the family. Families that include such professionals are less likely to suffer from chronic conditions, even conditional on income. They are 10 percent less likely than others to die before age 80. The effect is stronger for individuals with family incomes below the median. Parents in a family with a doctor are more likely to have their children receive HPV vaccinations and are less likely to smoke while their children are in utero.

To assess whether these effects are causal — that is, whether individuals are healthier of the health professional in their family — the researchers analyze a natural experiment in Swedish medical school admissions. The threshold for admission is a certain grade point average, but so many individuals exceed the threshold that admissions among the eligible group are randomized. The researchers find that families with a member who were admitted are healthier on average than families with an individual who applied to medical school but did not win the lottery. Eight years after an enrollee starts medical school, that person's older relatives are less likely to have a heart attack or heart failure and more likely to take medication to prevent heart attacks than the older relatives of those who applied to medical school but did not have the opportunity to attend. Younger relatives of the medical school enrollees benefit as well: they make larger preventive investments, are more likely to get vaccinated, and have fewer hospital admissions and addiction cases.

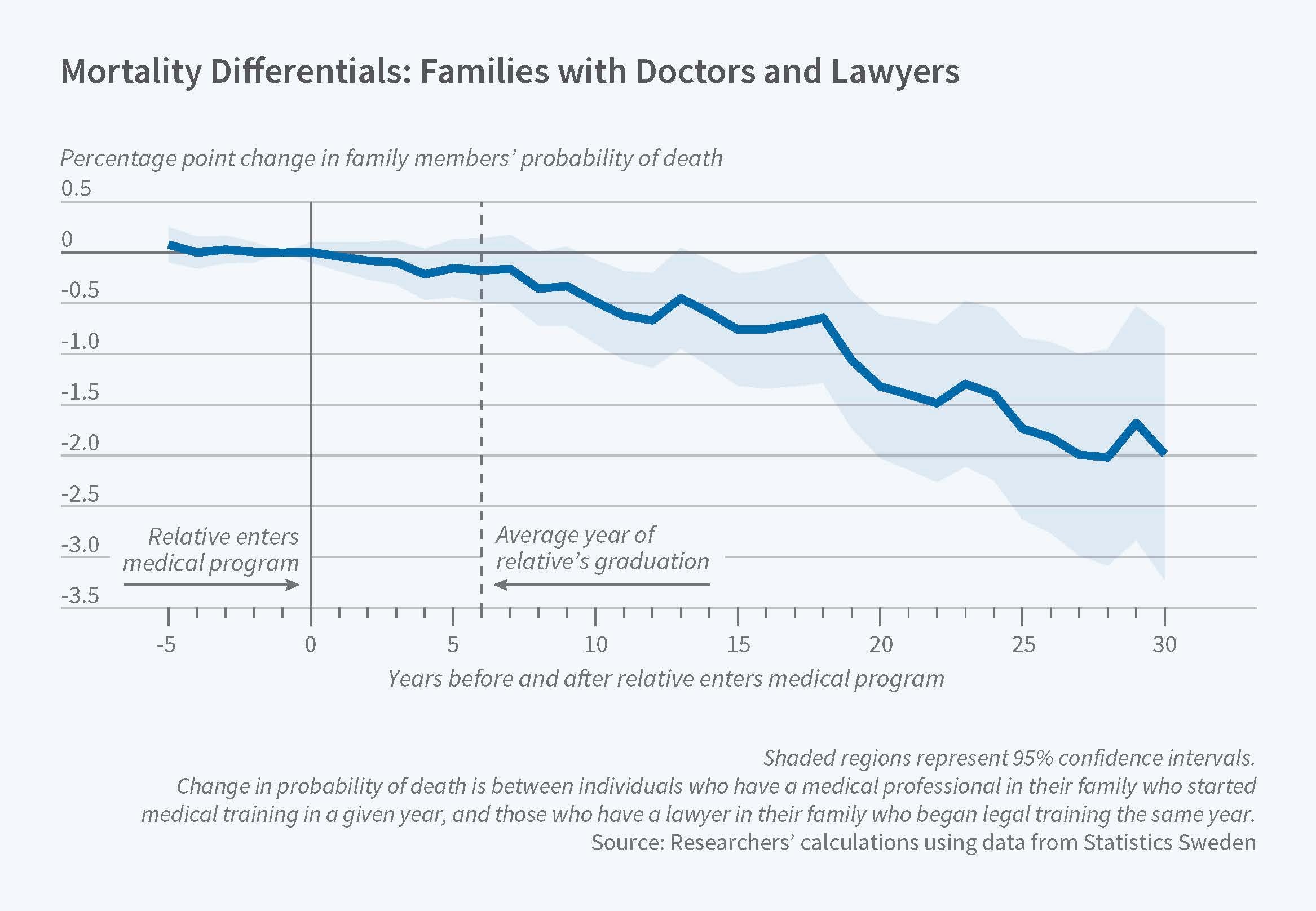

To analyze longer-term outcomes, the researchers compare family members' health before and after an individual receives a medical degree, relative to the health of those in families with a student who graduates from law school. They use families of law graduates as a control group, as law is another high-status, well-paid profession. A family member becoming a doctor reduces other members' mortality by 10 percent 25 years after the doctor graduates from medical school. It also lowers family members' rates of diabetes and lung cancer.

The researchers find evidence that the familial benefits are not due to preferential medical treatment, such as faster or better care. Rather, they find that the effects arise because of healthier habits and better decisions relating to preventive care. The effects are stronger if the medical professional is in one's nuclear family or lives in closer geographic proximity.

Based on their findings, the researchers estimate that expanding access to medical expertise could close up to 18 percent of the gap in health inequality with no negative impacts on higher-income families.

— Morgan Foy