Effects of Insurance Coverage on Infertility Treatments, Childbearing, and Wellbeing

Between 1995 and 2010, the share of births in Sweden that involved assisted reproductive technologies (ART) rose from 2 to 10 percent. These treatments range from low-cost drugs to costly and invasive interventions, such as in vitro fertilization (IVF).

In The Economics of Infertility: Evidence from Reproductive Medicine (NBER Working Paper 32445), Sarah Bögl, Jasmin Moshfegh, Petra Persson, and Maria Polyakova provide new evidence on the consequences of infertility and the role of insurance coverage in household decisions to initiate treatment. Using administrative, population-wide data for the period 2006–2019, the researchers estimate the use of infertility treatment. They find that over the course of their fertile years, one in eight women will experience primary infertility, defined as being childless and purchasing prescription drugs associated with any type of infertility treatment. This puts the lifetime prevalence of infertility on par with the lifetime risk of breast cancer.

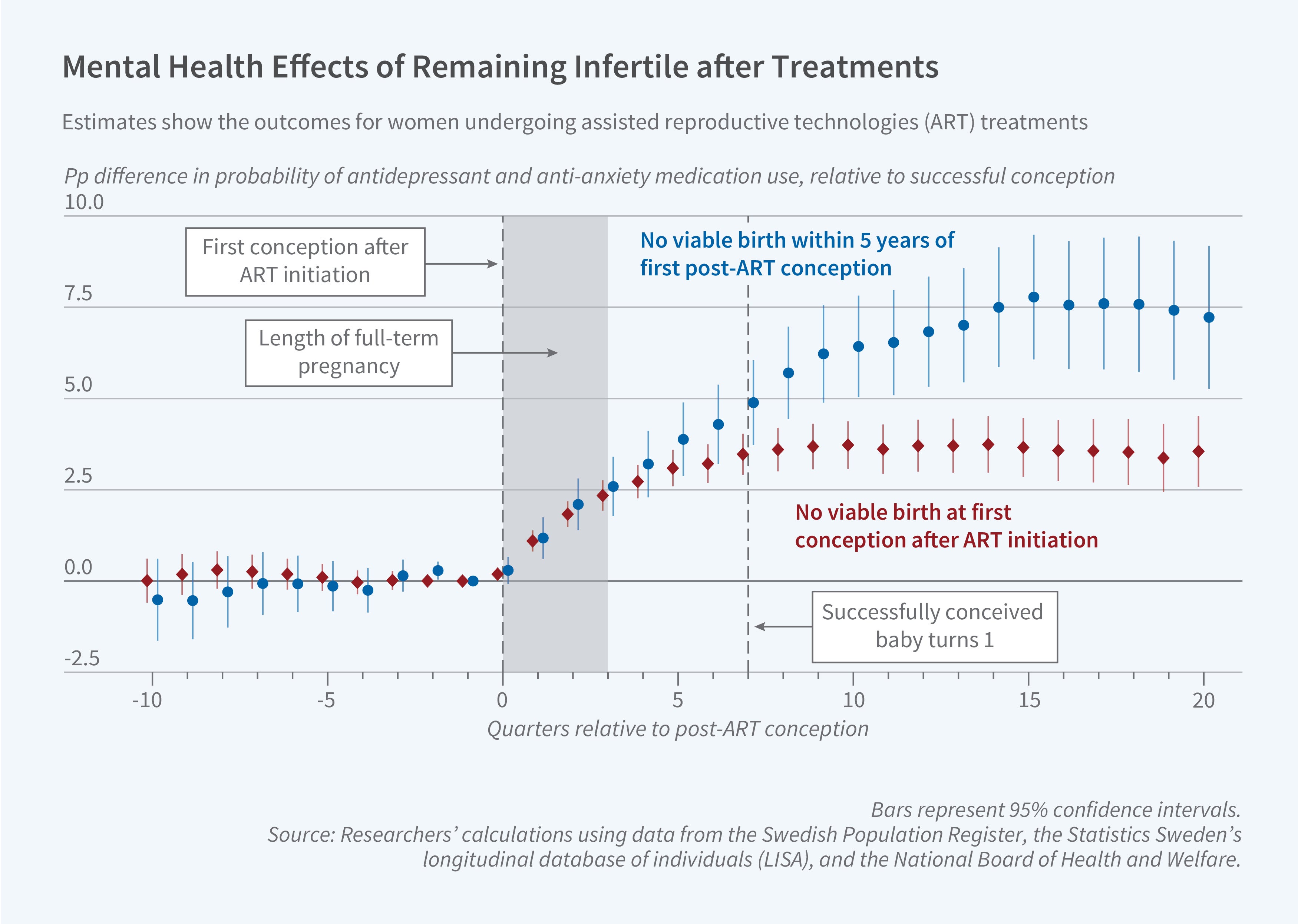

To understand the impact of persistent infertility on wellbeing, the researchers compare outcomes for women whose first conception after initiating any infertility treatment was unsuccessful, due to miscarriage or stillbirth, to outcomes for women whose first conception resulted in a live birth. The outcome of the initial conception after an infertility treatment is predictive of longer-term infertility: those whose first conception was unsuccessful are 33 percentage points less likely to have a child within five years.

Infertility has a negative effect on wellbeing. Women who are unable to have a child on their first conception after infertility treatments are 4 percentage points more likely to have purchased anti-anxiety or antidepressant prescription drugs and 2 percentage points more likely to get divorced than women whose first conception is successful. The effects are much larger for women who do not experience a birth within five years of the first post-ART conception and thus are likely to remain infertile in the long run. While in the short run the income of those who did not have a child is higher than that of women whose first post-ART conception was successful, this income differential closes within 10 years. The partners of the former group are also more likely to experience a deterioration of mental health and some loss of income in the long run.

Swedish women are eligible for public insurance coverage for IVF if they are younger than an age cutoff that varies from 36 to 39 depending on the region and year. The researchers use this discontinuous change in eligibility to examine the price sensitivity of IVF initiation and find that the rate of IVF initiation drops by half when treatment is not covered by health insurance, resulting in an equi-proportional decline in births.

Effects of insurance coverage are larger at the bottom of the income distribution than at the top, likely reflecting income differences in the ability to pay for costly infertility treatments. The researchers conclude that “insurance coverage policy thus constitutes a powerful tool that can affect the overall number of children and their allocation across the income distribution.”

— Lauri Scherer

The researchers acknowledge financial support from the National Science Foundation (CAREER SES-2144072, Persson), 2022 Stanford Discovery Innovation Fund (Polyakova), the National Institute on Aging (K01AG05984301, Polyakova), and the Sweden-America Foundation (Moshfegh).