Racial and Ethnic Disparities in SSDI Entry and Health

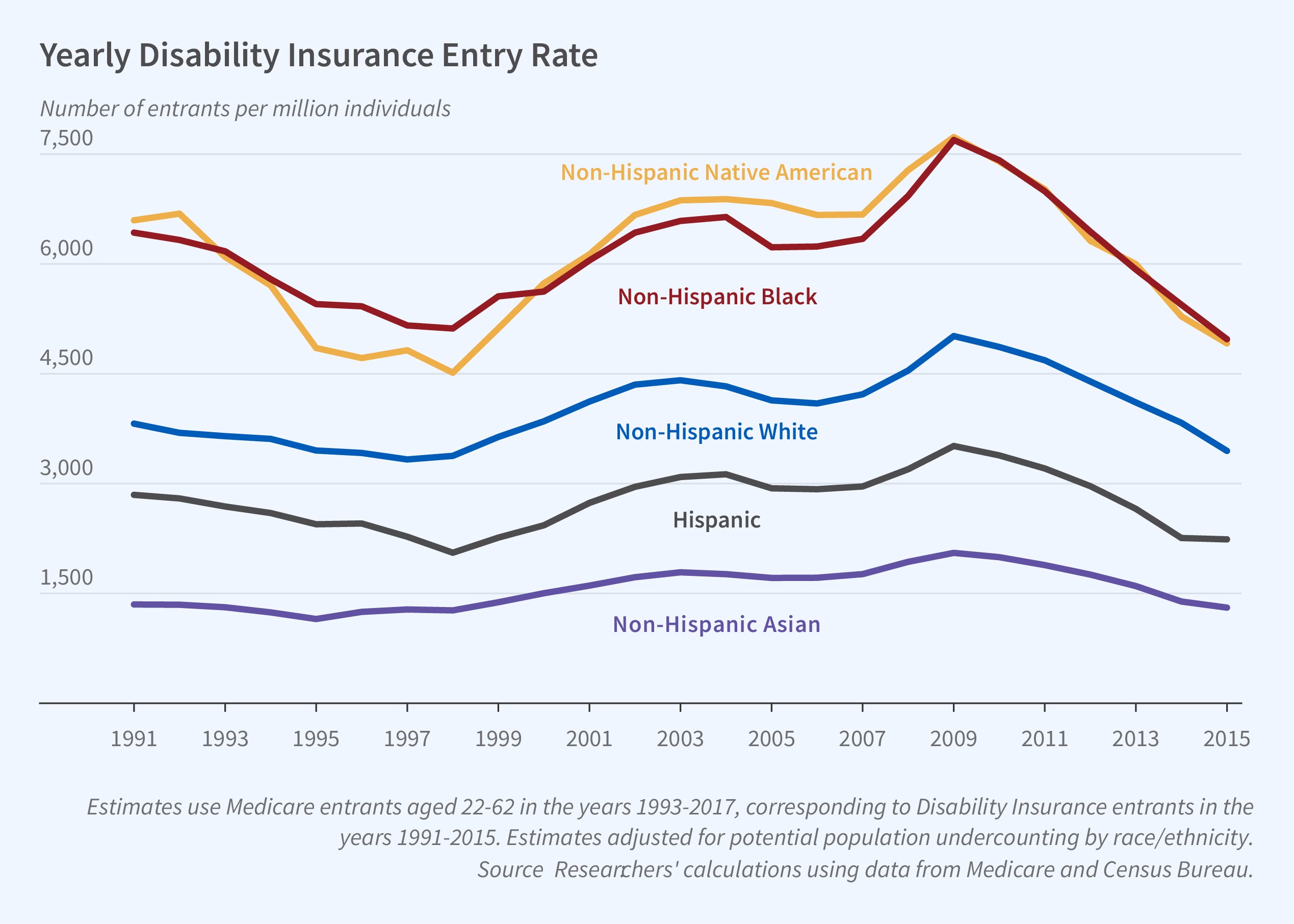

In a new study of Racial and Ethnic Disparities in SSDI Entry and Health (NBER RDRC Center Paper NB23-04), Colleen Carey, Nolan H. Miller, and David Molitor document significant racial and ethnic differences in the use of Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI). Non-Hispanic Blacks and Native Americans enter the SSDI program at the highest rates relative to their share of the population while non-Hispanic Asians enter at the lowest rates. Average health status, measured by medical expenditure and mortality, is worst among SSDI entrants who are non-Hispanic Blacks and Native Americans and best among Asians and Hispanics. Economic conditions affect SSDI claiming: every 1 percentage point increase in the local unemployment rate leads to roughly a 4.5 percent rise in entry for non-Hispanic Whites, Blacks, and Asians. Entry among Hispanics and Native Americans increases about half as much as for the other groups.

Non-Hispanic Blacks are 1.5 to 2 times more likely to receive SSDI benefits than Whites and 4 to 5 times more likely than Asians. They also are the group that uses the most medical care.

Although the Social Security Administration does not include race and ethnicity in its public-use SSDI databases, race identifiers can be obtained from Medicare records, as SSDI recipients qualify for Medicare benefits after a 24-month waiting period. After adjusting for potential undercounting by race/ethnicity, the researchers find that non-Hispanic Blacks and Native Americans are 1.5 to 2 times more likely to receive benefits than Whites and 4 to 5 times more likely than Asians. Non-Hispanic Blacks also spend about 40 percent more on medical care than non-Hispanic Whites and Asians.

The SSDI program uses a five-step process to determine whether applicants have disabilities that limit their ability to work. To qualify, they must be unemployed and diagnosed with a significant work-limiting condition likely to last for at least a year. The program also considers whether they can do other work, which takes other factors into account, such as their level of education. Those found unable to perform sustained work receive cash benefits and health insurance through Medicare.

These eligibility rules are relaxed for applicants at age 50 and again at age 55 and over. Participation jumps for all races when these milestones are reached, particularly at age 50 when it surges by 79 percent for non-Hispanic Native Americans, 78 percent for Hispanics, and 73 percent for non-Hispanic Blacks. Hispanic White participation surges by 64 percent and Asian participation surges by 51 percent.

Because of limitations in the data, conclusions should be drawn carefully, the researchers caution. For example, non-Hispanic Blacks could be more likely to enter SSDI because, on average, they have more medical conditions that limit their ability to work. It is also possible, however, they do not gain access to the program until their medical conditions have progressed further and become more severe than for individuals in other groups. The researchers only have data on the health outcomes of SSDI recipients; they do not have information on those who are not admitted.

– Laurent Belsie

Research reported in this paper was supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under award number P01AG005842 and was performed pursuant to grant RDR18000003 from the SSA funded as part of the Retirement and Disability Research Consortium. The opinions and conclusions expressed are solely those of the authors and do not represent the opinions or policies of the NBER, NIH, SSA, or any agency of the federal government.