Do Drug Monitoring Programs Reduce the Misuse of Opioids?

While prescription opioids are an effective analgesic, their use presents a risk of addiction and overdose. Deaths from opioid poisoning in the United States quadrupled between 1999 and 2010, during a period when the use of prescription opioids rose by 300 percent.

The rising rate of opioid addiction and mortality has galvanized the attention of the public and spurred a number of policy responses, particularly at the state level. Nearly every state has created a Prescription Drug Monitoring Program (PDMP), which collects data on prescriptions for controlled substances to facilitate detection of suspicious prescribing and utilization.

In The Effect of Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs on Opioid Utilization in Medicare (NBER Working Paper No. 23148), researchers Thomas Buchmueller and Colleen Carey explore whether state monitoring programs have reduced the misuse of opioids in Medicare.

A PDMP allows authorized individuals to view a patient's prescribing history in order to identify patients who may be misusing opioids or diverting them to street sale for non-medical use. However, establishing a PDMP does not ensure that the data will be used. Some early state programs had provisions that limited provider access, and even in states without such provisions, only a small share of providers have used them to access patient histories. Perhaps unsurprisingly, previous studies have found little effect of PDMPs on opioid use or health outcomes.

During the past decade, ten states have enacted laws requiring providers to access the PDMP prior to prescribing under certain circumstances. In this study, the researchers seek to improve on the past literature on PDMPs by distinguishing between the effects of programs with and without these "must access" requirements. They evaluate the effect of PDMPs on the prescription drug utilization of Medicare beneficiaries, using claims data for enrollees in Part D and traditional fee-for-service Medicare during the period 2007 to 2013.

Use of opioids is very common in this population — in any six-month period, 28 percent of beneficiaries fill at least one prescription for opioids. To distinguish between appropriate and inappropriate use of these drugs, the researchers develop several measures of misuse. A first set of measures is quantity-based, such as obtaining more than a seven-month supply of drugs over a six-month period, having multiple prescriptions for the same drug at the same time, or having prescriptions that translate to a "morphine-equivalent dosage" (MED) above a threshold established in provider guidelines. A second set of measures captures "shopping" behavior, such as visiting multiple prescribers or pharmacies to obtain opioids, using out-of-state pharmacies (whose prescriptions are not reported to the home state's PDMP), or having a large number of new patient visits (which may reflect opioid-seeking behavior). The researchers also look at the incidence of opioid poisonings, measured as cases where the diagnosis code "opioid-related overdose" appears on a medical claim.

The degree of misuse varies depending on the measure used. While 8.9 percent of opioid takers obtain more than a seven-month supply in six months and 9.2 percent have overlapping claims for the same drug, only 1.7 percent obtain an MED above the guideline. Some 2.3 percent of opioid users receive prescriptions from five or more providers during a six-month period, 0.6 percent use more than five pharmacies, and 1.3 percent have more than four new patient visits over six months. The rate of opioid poisonings is 0.2 percent.

The researchers first examine the effect of PDMPs that lack a "must access" requirement, comparing them to states without a PDMP. They fail to find any significant effect of these reporting programs on opioid misuse, consistent with the past literature and with the low usage of non-"must access" PDMPs by providers.

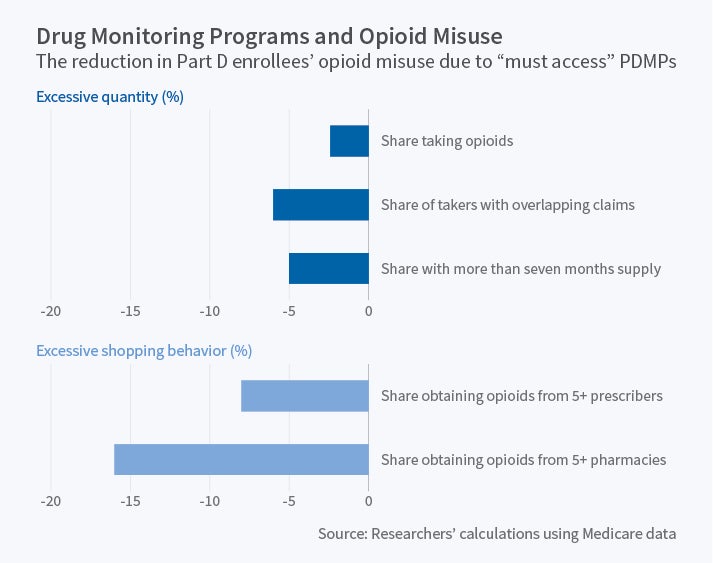

Next, they compare outcomes in states with "must access" PDMPs to those in states with non-"must access" reporting programs or without a program. They find that having a "must access" program is associated with a 2.4 percent decline in the share of Part D enrollees taking opioids, as well as with a 5 percent decline in the share with more than a seven-month supply and a 6 percent decline in the share with overlapping claims; there is no change in the share with prescriptions above the MED threshold. There is a substantial decline in shopping behavior, with an 8 percent drop in the share with prescriptions from five or more providers and a 16 percent drop in the share using five or more pharmacies. There is a 14 percent decrease in the share with more than four new patient visits, and the researchers estimate that having a PDMP in every state would save $350 million per year in charges for such visits. However, there is no evidence that PDMPs lower opioid poisonings.

The study's results suggest that "must access" PDMPs curb certain types of extreme utilization of opioids. At the same time, there is no evidence that PDMPs affect opioid poisonings. As the researchers suggest, one possible explanation for this finding is that Medicare beneficiaries who are misusing opioids may be able to find other ways to maintain consumption, such as street sources of prescription opioids or heroin. Another possibility is that "must access" PDMPs reduce the rate at which individuals become opioid misusers and will reduce poisonings in the future, beyond the study period. The researchers conclude by noting that changes to state-based opioid use registries, as well as new initiatives for Medicare beneficiaries by the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services, make it important for researchers to continue to study these policies.