The Heterogeneous Effects of Medicaid Expansion on Disability Employment

Following the 2010 Affordable Care Act, 39 states and the District of Columbia have expanded Medicaid to cover virtually all adults with incomes up to 138 percent of the federal poverty level Existing studies have reached differing conclusions as to the effect of Medicaid expansion on employment outcomes for people with disabilities.

One potential reason for the lack of consensus is that Medicaid expansion may affect employment differently for different groups within the disability community. For some people with disabilities, Medicaid expansion may weaken the incentive to exit the labor force to apply for Supplemental Security Income (SSI) and receive Medicaid (as SSI beneficiaries are eligible for Medicaid in all but 10 states) or Social Security Disability Insurance and receive Medicare (as SSDI beneficiaries are eligible to receive Medicare after two years) by providing an alternative pathway to access public insurance. Similarly, for those currently receiving SSI or SSDI, Medicaid expansion may strengthen the incentive to re-enter the labor force by offering a means to maintain Medicaid coverage. Conversely, Medicaid expansion could make it easier for disabled workers to exit the labor force at disability onset by removing the need to continue working to obtain health insurance, thus reducing “job lock.”

In Disability Heterogeneity in the Impact of the ACA’s Medicaid Expansions on Disability Employment (NBER RDRC Working Paper 21-13), researchers Ari Ne’eman and Nicole Maestas examine the impact of Medicaid expansion on different groups within the disabled population, with the purpose of assessing whether disability heterogeneity may help explain the divergent findings in prior work.

The authors use the Current Population Survey (CPS) in their analysis. The CPS uses a six-question sequence to identify people with disabilities and asks about disability status in two interviews one year apart, while also collecting information on current employment status at each interview. This design allows the authors to subdivide those who report being disabled at the later interview by whether the disability is new or ongoing and whether the person has higher or lower labor force attachment (based on employment at the earlier interview). In their analysis, the authors treat the expansion of Medicaid in different states in different years as a natural experiment that can be used to compare changes over time in employment outcomes in expansion states to changes in nonexpansion states.

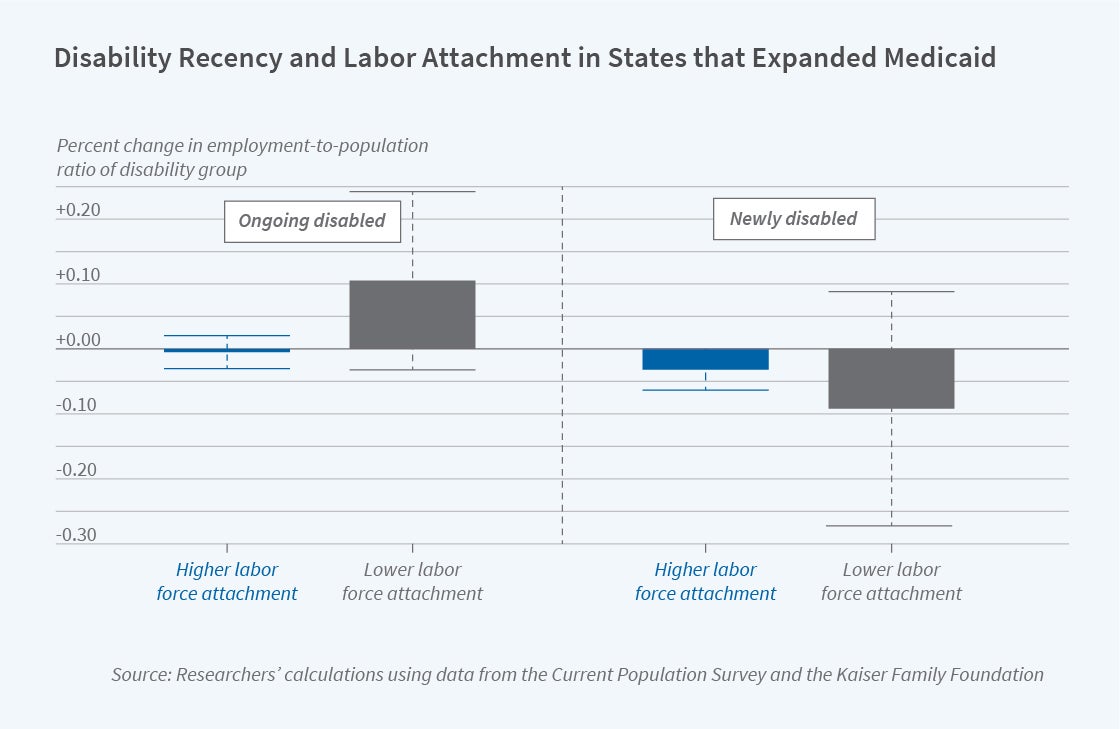

The results indicate that Medicaid expansion may have had heterogeneous effects on the employment of people with disabilities. The authors find that for those with ongoing disabilities and higher labor force attachment, there is no effect of expansion on employment, and they obtain a sufficiently precise estimate to rule out anything other than a very small positive or negative effect. By contrast, for those with ongoing disabilities and lower labor force attachment, there is suggestive evidence of an increase in employment, indicating some return to working among this population, but this effect must be interpreted with caution because it is not statistically significant and is imprecisely estimated.

For those who are newly disabled and have high labor force attachment, the authors find suggestive evidence that Medicaid expansion leads to a 3 percent decrease in employment, indicating that access to health insurance outside of employment may reduce job lock. While the past literature has tended to find no effect of the post-ACA expansion of Medicaid on job lock, the authors note that they study a population for whom early retirement with access to health insurance may be particularly valuable. They find that for the newly disabled with low labor force attachment, Medicaid expansion may have lowered employment by as much as 9 percent, though this effect is not statistically significant.

In sum, the results indicate that disability heterogeneity may explain the conflicted state of the literature, “with different study designs and data choices picking up distinct signals pointing in different directions.” The authors conclude that “accounting for disability heterogeneity allows for more precise estimates of policy impacts for some populations while providing suggestive evidence of countervailing treatment effects for others.” The authors’ work is ongoing to validate these findings in other samples and for alternative definitions of disability, particularly the imprecise estimates for those with ongoing disabilities.

The research reported herein was performed pursuant to grant RDR18000003 from the US Social Security Administration (SSA) funded as part of the Retirement and Disability Research Consortium and grant 90RTEM0006 01 00 from the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research (NIDILRR) to the Disability-Inclusive Employment Policy (DIEP) Rehabilitation Research and Training Center (RRTC). The opinions and conclusions expressed are solely those of the author(s) and do not represent the opinions or policy of SSA, NIDILRR, any agency of the Federal Government, or the NBER. Neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of the contents of this report. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not necessarily constitute or imply endorsement, recommendation or favoring by the United States Government or any agency thereof.