Effects of Medicaid Privatization in Texas

Public health insurance can be administered directly by the government or provided through private insurance firms. In the US, over 80% of Medicaid beneficiaries and one-third of Medicare beneficiaries receive their benefits through a private health plan. In theory, private provision may result in lower costs, since firms have an incentive to keep spending low in order to maximize profits. One potential concern is that reduced spending may adversely affect the quality of care, although government oversight and competition for patients may help to ensure that spending is not too low. Private insurers may also seek to avoid the sickest patients if they are not fully compensated for the higher costs.

In “Private vs. Public Provision of Social Insurance: Evidence from Medicaid” (NBER Working Paper 26042), researchers Timothy Layton, Nicole Maestas, Daniel Prinz, and Boris Vabson investigate the effects of shifting Medicaid coverage from public to private provision for adults with disabilities in Texas.

Disabled Medicaid beneficiaries are a population of particular interest, as they represent 14 percent of all Medicaid beneficiaries nationally yet are responsible for 40 percent of Medicaid spending. While most non-disabled Medicaid beneficiaries have already been transitioned to private insurance, the transition of disabled beneficiaries is now underway in many states, making it important to learn whether the effects of privatization in this group are the same as in the non-disabled population.

The authors make use of a policy change in the mid-2000s, when the state of Texas transitioned adults with disabilities – most of whom qualified for Medicaid due to their enrollment in the federal Supplemental Security Income (SSI) program – from the state-run insurance plan to private Medicaid plans. As this change was implemented in only a subset of counties, the authors compare how spending changed after privatization in affected vs. unaffected counties. This strategy surmounts the usual difficulty that people who voluntarily elect private insurance may differ from those who remain in the public plan in ways that affect their spending and health outcomes.

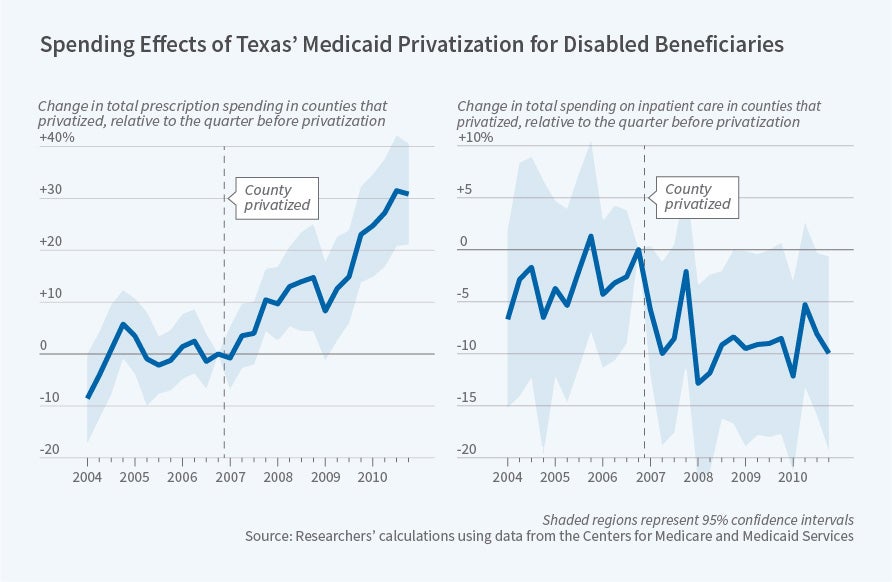

The authors find that private provision leads to higher spending on prescription drugs – four years after the transition, spending was 30 percent higher in affected counties. The limiting of drug use to three drugs per month under Texas’ publicly-administered Medicaid plan appears to help explain this result. Privatization led to an increase in the use of more than three drugs per month and in the use of drugs such as insulin, anti-psychotics, anti-depressants, statins, and asthma and pain medications. This suggests that the cap in the state plan was binding for a meaningful share of disabled beneficiaries and reduced access to drugs that can be used to treat chronic conditions prevalent in this population.

Second, the authors find that privatization leads to increased outpatient medical spending. There was an 8 percent increase in the utilization of care and private plans also paid rates that were 8 percent higher on average. These findings suggest that the lower reimbursement rates for providers in the state plan may have served to ration access to care.

Third, the authors find that inpatient spending decreased by at least 8 percent after privatization. This finding is unlikely to represent private plans rationing access to inpatient care since inpatient spending for disabled Medicaid beneficiaries is carved out of private plan contracts and paid for directly by the state. Indeed, as the decrease in admissions was concentrated among admissions for mental illness, diabetes, and respiratory conditions – often considered avoidable given proper disease management – this decrease is likely linked to greater access to prescription drugs and efforts by plans to manage enrollees’ chronic conditions.

Overall, privatization was associated with a 12 percent increase in total spending, as capitation payments to private insurers were set higher than the actual fee-for-service costs of the state plan. However, the authors find that 80 percent of this higher spending was passed on to beneficiaries in the form of increased utilization. Also, the finding that privatization was associated with an increase in the use of drugs used to treat chronic conditions and a decrease in avoidable hospitalizations strongly suggests that privatization is associated with an improvement in the quality of health care and in actual health.

The authors note that their findings run counter to the consensus in the policy community that private plans save money and to the conventional wisdom among economists that privatization in Medicaid leads to worse outcomes. Pointing to important features of the Texas public plan such as the drug cap, the authors note “the design of both the private and the public programs matter for determining the effects of public vs. private provision.” They conclude “private provision of Medicaid services ultimately likely benefits adults with disabilities in some settings.”

The authors acknowledge financial support from the Laura and John Arnold Foundation, the Social Security Administration through grant #5DRC1200002-06 to the NBER as part of the SSA Disability Research Consortium, the National Institute on Aging (P30-AG012810), and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (K01-HS25786-01).