SNAP Eligibility Enforcement and Program Adoption

The US safety net provides a wide variety of supports for low-income families from food assistance like the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) to wage subsidies like the Earned Income Tax Credit. However, receipt of these benefits among eligible households is not automatic — households must actively apply to each program from which they seek benefits. Enrollment processes often include lengthy procedures associated with demonstrating need or complying with other eligibility criteria during both the initial application and recertification periods.

The benefits of completing these administrative requirements are substantial — for example, the average SNAP participant receives roughly $2,500 per year in benefits. However, recent research on administrative burdens in government programs suggests that seemingly small barriers to program access, such as additional forms or the distance to a program office, significantly depress take-up rates.

My collaborators and I contribute to the literature in two related papers by exploring the effect of a common program application requirement — the caseworker interview — on SNAP participation.

SNAP Enrollment Process

SNAP is the largest nutrition assistance program in the US, providing food vouchers worth $113 billion to over 40 million low-income individuals in fiscal year 2023. Benefits vary by income and household size, with maximum benefits for a family of four at just under $1,000 per month.

Applicants must complete three steps in order to enroll in the program. First, they must submit an application providing details required to assess the eligibility of all potential recipients in the household, such as residency, immigration status, and income. Applicants must then provide documentation verifying the information listed in the application, such as a driver’s license or pay stubs. As a final step, the applicant must complete an interview, either over the phone or in person, with a SNAP caseworker. These interviews provide a touchpoint with a SNAP administrator to help guide the applicant through the process or resolve any discrepancies in the application. At the same time, the interview is a regulatory requirement. This means that applicants who fail to complete an interview within 30 days of submitting an application are procedurally denied, even if they are otherwise deemed eligible.

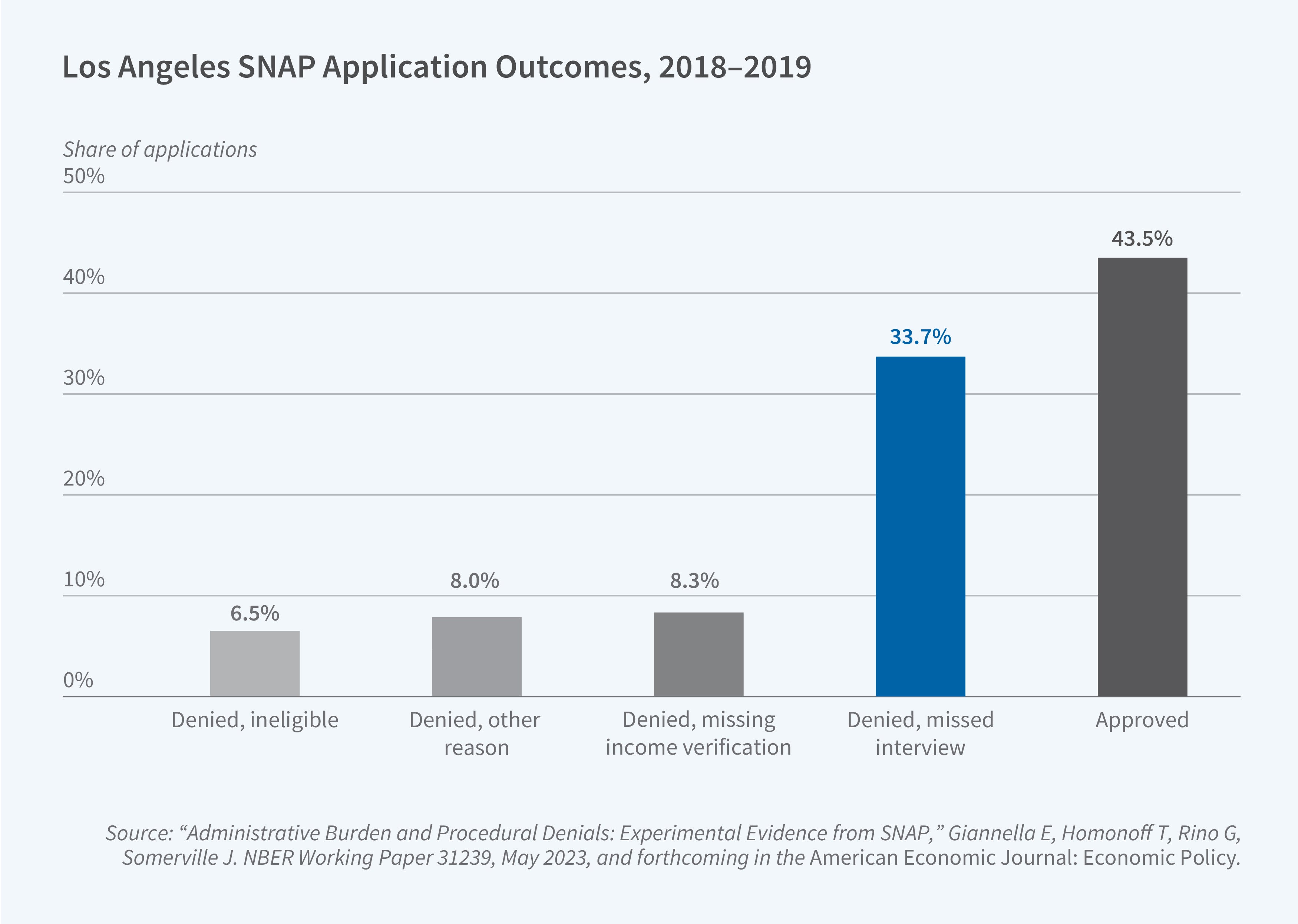

Procedural denials are not a rare occurrence. Figure 1 shows that in Los Angeles County, the county with the second highest SNAP caseload in the country, one-third of all applications are denied due to a missed interview—more than for all other reasons for denial combined.1 This suggests that administrative barriers, especially those related to the caseworker interview, are a key factor leading to incomplete take-up.

Los Angeles Flexible Interview Experiment

One potential reason for the high rates of denials associated with missed interviews relates to how the interviews are conducted. In California, as in the majority of states, interviews are scheduled by program administrators without input from the applicant regarding availability. Applicants are informed of their interview date via an appointment letter sent to their home address, which they may or may not receive before their scheduled appointment. Applicants who miss their appointment may reschedule their interview but often cite difficulties connecting with their local SNAP offices to do so.

Eric Giannella, Gwen Rino, Jason Somerville, and I study the impact of an overhaul to the SNAP interview process in Los Angeles County, which allowed for flexible, client-initiated interviews. We evaluate this programmatic change using a randomized controlled trial involving 65,000 SNAP applicants. Applicants assigned to the control group received an appointment letter along with business-as-usual texts and email communications letting them know they should expect a call from the county to complete their interview. Applicants assigned to the treatment group received modified communications providing them with the number of a newly established call center they could call to complete an interview at their convenience in lieu of the scheduled interview in their appointment letter.

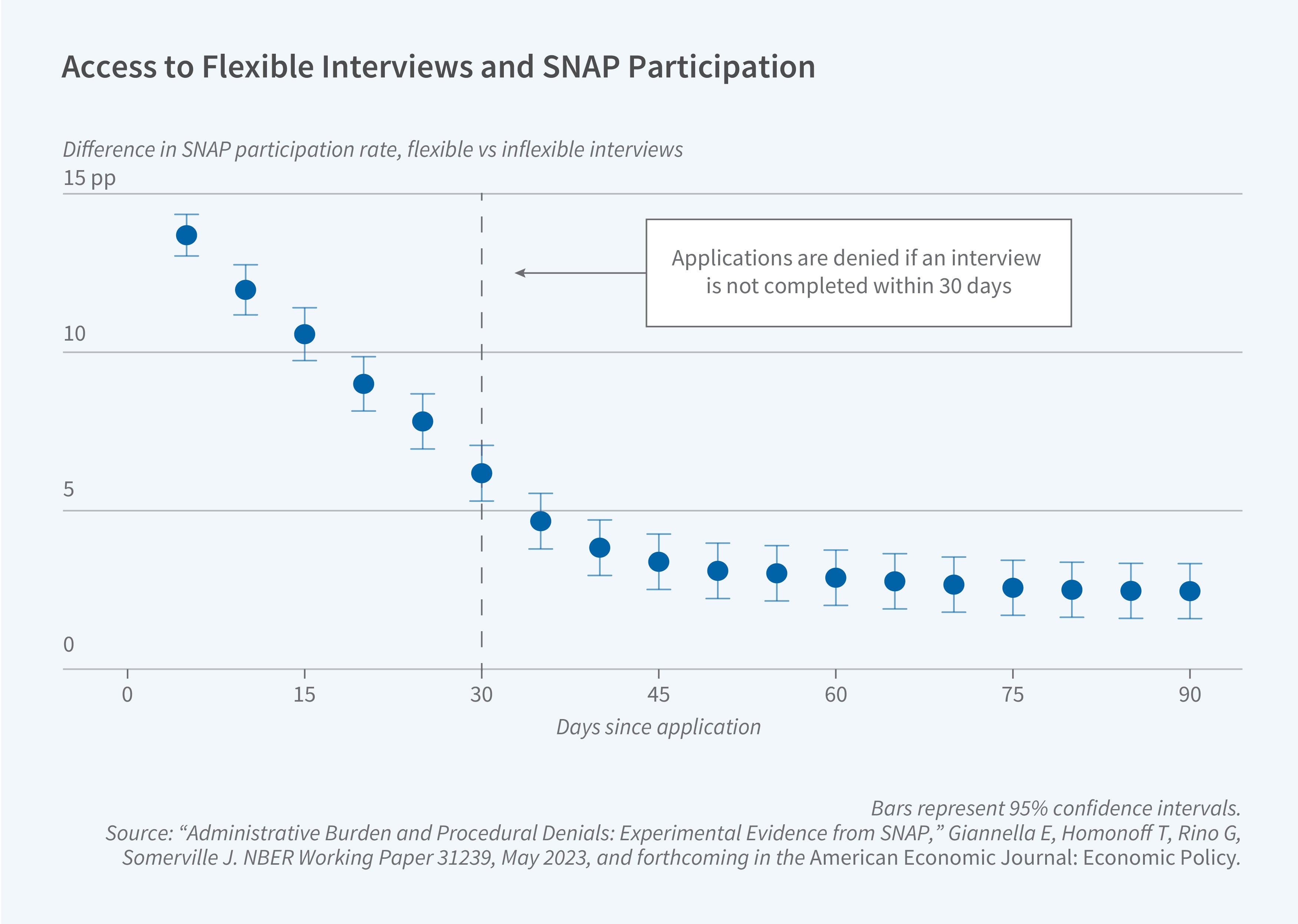

We find that access to the flexible interview process expedited the time to approval, increased approval rates, and increased long-term SNAP participation. To show this, Figure 2 presents the difference in the SNAP participation rate between the treatment and control groups by days since initial application submission.2 Early approvals are twice as high in the treatment group as in the control group (27 versus 14 percent at day 5), and treatment group members are over 6 percentage points more likely ever to be approved by day 30, the deadline for completing the application process. After the deadline, initially denied control group members partially catch up to the treatment group through successful reapplication to the program. However, the gap between the two groups does not disappear: treatment group members are over 2 percentage points more likely to receive SNAP benefits even several months after the initial application.

SNAP Recertification and Interview Timing

The initial application process establishes that SNAP enrollees are eligible for the program at the time of application. To ensure that SNAP recipients have maintained eligibility over time, they must periodically recertify for the program, typically every six to twelve months. The recertification process closely mirrors the steps required for initial enrollment: participants must complete a recertification application, submit supporting documentation, and complete a caseworker interview. Many studies document high rates of SNAP exit at recertification, yet it remains unclear whether these households left the program because they were no longer eligible or procedurally denied.

Somerville and I provide evidence that a sizeable fraction of program exits at recertification were among eligible cases.3 Using administrative data on the universe of recertification cases in San Francisco over a two-year window, we show that roughly half of all cases fail recertification, yet the vast majority (94 percent) of rejected cases have earnings below the eligibility threshold and roughly two-thirds of rejected cases have no wage earnings at all. Moreover, half of the recertification failures successfully reenter the program in the following months, an outcome referred to as “program churn.” For these exit patterns to be driven solely by fluctuations in eligibility, it would imply that one-quarter of all SNAP cases are ineligible at the time of recertification yet once again eligible almost immediately after being discontinued from the program.

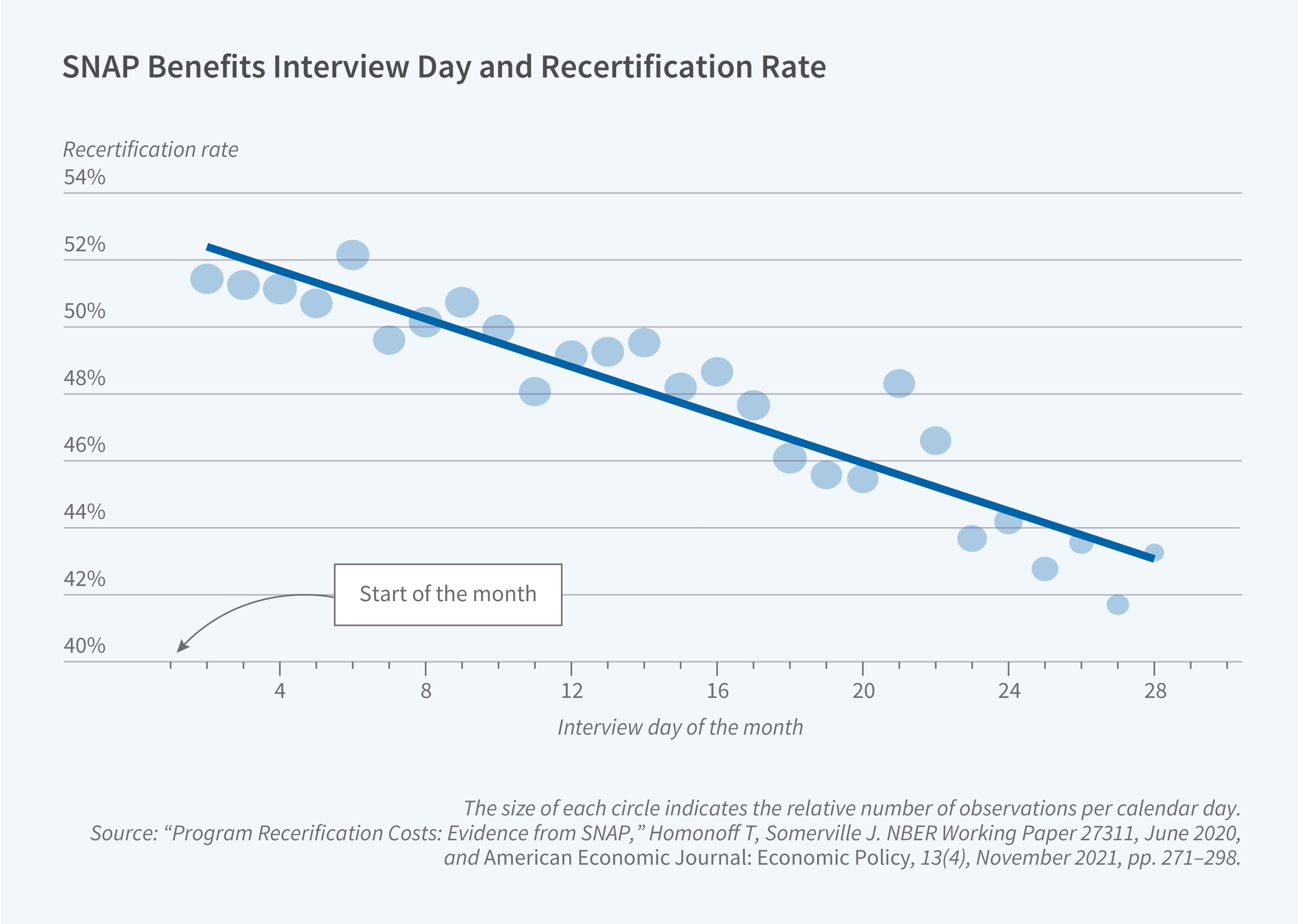

An alternative explanation for the high observed rate of program churn is that the recertification requirements create another administrative hurdle that results in the loss of benefits among eligible households. We explore this possibility by once again analyzing the administration of the caseworker interview requirement, this time focusing on the timing of the scheduled recertification interview. In San Francisco, SNAP cases must recertify for the program each year, with all certification periods closing at the end of the calendar month. Initial interview assignments are staggered throughout the calendar month and randomly assigned to each case in an effort to smooth caseworker workloads. This means that cases assigned to the earliest interview date have four weeks before the recertification deadline to reschedule a missed interview or gather any missing documentation, while cases assigned to the latest date have only a few days.

Figure 3 plots the relationship between the assigned interview day and the recertification rate.4 Cases assigned to interviews at the end of the month are 20 percent less likely to successfully recertify than cases assigned to interviews at the start of the month. We also find that the relationship between interview assignment timing and SNAP participation persists long term. Cases assigned to the latest interview date are over 2 percentage points less likely to participate in SNAP at any point in the year after recertification than cases assigned to the earliest date. This suggests that while the majority of cases who exit the program due to later interview assignments eventually reenter the program, roughly one-quarter of the cases who fail recertification due solely to the timing of their interview remain off the program long term. The benefit losses are sizeable: on average, the marginal disenrolled case loses $550 in SNAP benefits in the first year alone.

Conclusion

Programs that target benefits toward low-income households require eligibility standards to ensure that benefits are received only by the intended individuals. Our research highlights the costs associated with enforcement of these program integrity policies: incomplete program take-up. Among likely eligible households, we document sizeable losses in SNAP benefits and exits from the program associated with the interview requirement. It is worth noting that the caseworker interview is only one potential barrier to program access — enrollment and recertification procedures entail many other steps to establish eligibility that may also decrease take-up. Our findings, therefore, provide just one example of how seemingly minor elements of program integrity policies can generate outsize effects on benefit access among eligible households, and underscore the importance of weighing these costs against the targeting benefits of the regulation when designing safety net policies.

Endnotes

“Administrative Burden and Procedural Denials: Experimental Evidence from SNAP,” Giannella E, Homonoff T, Rino G, Somerville J. NBER Working Paper 31239, May 2023, and forthcoming in the American Economic Journal: Economic Policy.

“Program Recertification Costs: Evidence from SNAP,” Homonoff T, Somerville J. NBER Working Paper 27311, June 2020, and American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 13(4), November 2021, pp. 271–298.