Borrowers Aware of FICO Scores Are Less Likely to Be Over-due

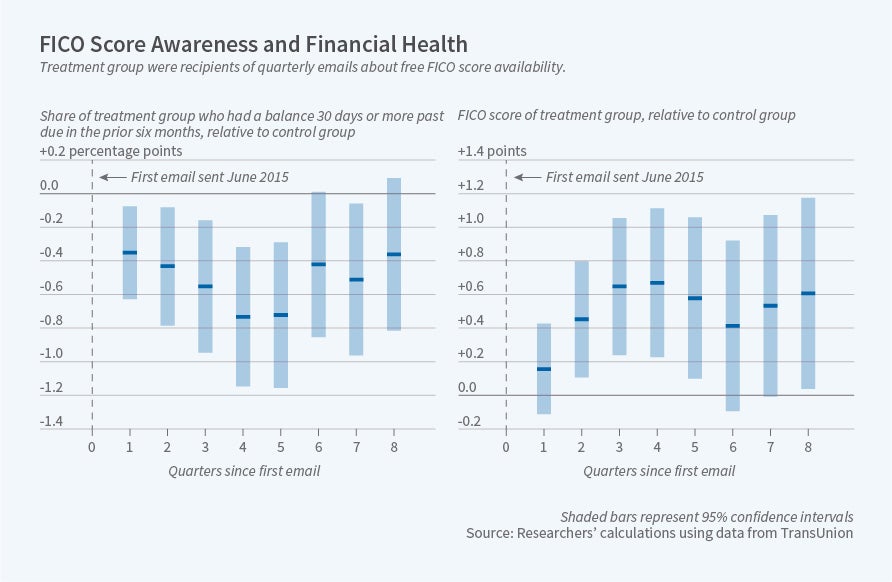

Quarterly emails about logging on to the Sallie Mae website to view FICO scores affected patterns of debt repayment.

Failing to make minimum payments on credit accounts is a common and costly behavior for many borrowers. Recent research from the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau suggests that, every quarter, 20 percent of consumer credit accounts are assessed a late fee. The cost of the associated late payments can be high, and tardy payments can lower consumers’ credit scores and increase interest rates on future loans.

In Does Knowing Your FICO Score Change Financial Behaviors? Evidence from a Field Experiment with Student Loan Borrowers (NBER Working Paper No. 26048), Tatiana Homonoff, Rourke O’Brien, and Abigail B. Sussman test the effect of an intervention designed to raise consumer awareness of the consequences of late payments.

Beginning in 2015, as part of the FICO Score Open Access initiative, the student loan institution Sallie Mae began providing its borrowers with unlimited access to their FICO scores. The researchers randomly assigned over 400,000 Sallie Mae clients into a control group and three treatment groups. Consumers in the treatment groups received various forms of quarterly email reminders that they could log on to the Sallie Mae website and view their FICO scores, along with instructions for accessing the information. In the first year of the experiment, 32 percent of treatment group consumers viewed their score at least once, 8 percentage points more than those in the control group.

Using data on borrowers’ credit scores and histories, the researchers found that treatment-group consumers were 4 percent, or 0.7 percentage points, less likely than control-group consumers to have an account more than 30 days past due. The intervention also improved borrowers’ FICO scores by 0.7 points. The effects were similar across the three different treatment groups — a baseline group which received instructions on accessing scores, a second group which received instructions and information about the economic consequences of their scores, and a third group which received instructions and information about peers’ behaviors. Treatment-group borrowers who viewed their scores as a result of the intervention were 9 percentage points less likely to have a past-due account, and enjoyed an 8.2 percentage point increase in their FICO scores.

The researchers also tested the effectiveness of the intervention on a smaller group of borrowers who only received the reminders for the first three quarters of the two-year intervention. They found no statistically significant differences in outcomes between members of this group and those who received the full two years’ worth of reminders.

To shed further light on the mechanisms behind this change in payment patterns, the researchers analyzed a subset of borrowers’ responses to a survey administered one year after the intervention began. They found that treatment-group borrowers were more likely to report their FICO scores accurately and were less prone to overestimation. The researchers note that this finding “suggests the intervention may lead to behavior change, in part by allowing people to properly calibrate their creditworthiness.” They did not, however, find any effects of the intervention on more general financial knowledge. Treatment-group borrowers did not perform better on a financial literacy quiz, did not express higher levels of familiarity with FICO scores, and did not exhibit an improved ability to correctly identify any individual credit behavior as positive or negative.

“Our findings demonstrate the potential for targeted, low-cost, scalable interventions to positively impact financial decision making,” the researchers conclude.

— Dwyer Gunn