Influencing Retirement Savings Decisions with Automatic Enrollment and Related Tools

Historically, retirees in the US relied on the “three-legged stool” of Social Security, defined benefit (DB) pension plans, and personal savings to provide retirement income.1 Beginning in the late 1970s, however, access to DB plans began to fall while access to defined contribution (DC) plans, which require individuals to make their own savings plan contributions and investment decisions during their working years, rose.2 As of December 2023, retirement assets in DC plans — e.g., 401(k)s — and individual retirement accounts (IRAs) totaled $24.1 trillion, with 56 percent of those assets held in IRAs. Nearly two-thirds of IRAs contained funds rolled over from 401(k)s or other employer-sponsored retirement plans. By comparison, DB plans held $11.8 trillion.3

While households now have more power to decide how much to save and how to invest it, many save little during their working years. About one-quarter of Americans aged 65 or older receive 90 percent or more of their household income from Social Security.4 We have spent the past 25 years investigating how plan design features influence individuals’ savings behavior, which is all the more important as DC plans now serve as a critical savings vehicle for retirement preparation.

Here, we summarize this research stream in three sections. The first section describes our early research documenting that automatically enrolling individuals in their employer-sponsored DC plan has a powerful impact on their participation, contribution, and asset allocation outcomes. The second section discusses research on DC plan features other than automatic enrollment that also influence savings outcomes and that simultaneously illuminate mechanisms responsible for automatic enrollment’s effects. The third section reports results from our recent work examining individual decisions that undermine the ultimate impact of automatic enrollment and auto-escalation on long-run wealth accumulation. Although not all of us coauthored every paper summarized, for economy of expression, we will describe them as papers “we” wrote.

Automatic Enrollment and 401(k) Participation, Contributions, and Asset Allocations

Most households believe that they need to save for retirement, but following through is challenging. A survey we ran in 2001 showed that among employees of a large US employer, 68 percent felt they were saving too little, 24 percent planned to start saving more in the near future, and only 3 percent actually followed through.5 This inertia can lead to low savings if the status quo is not to save. Automatic enrollment turns this logic on its head by harnessing inertia to generate contributions to DC plans.

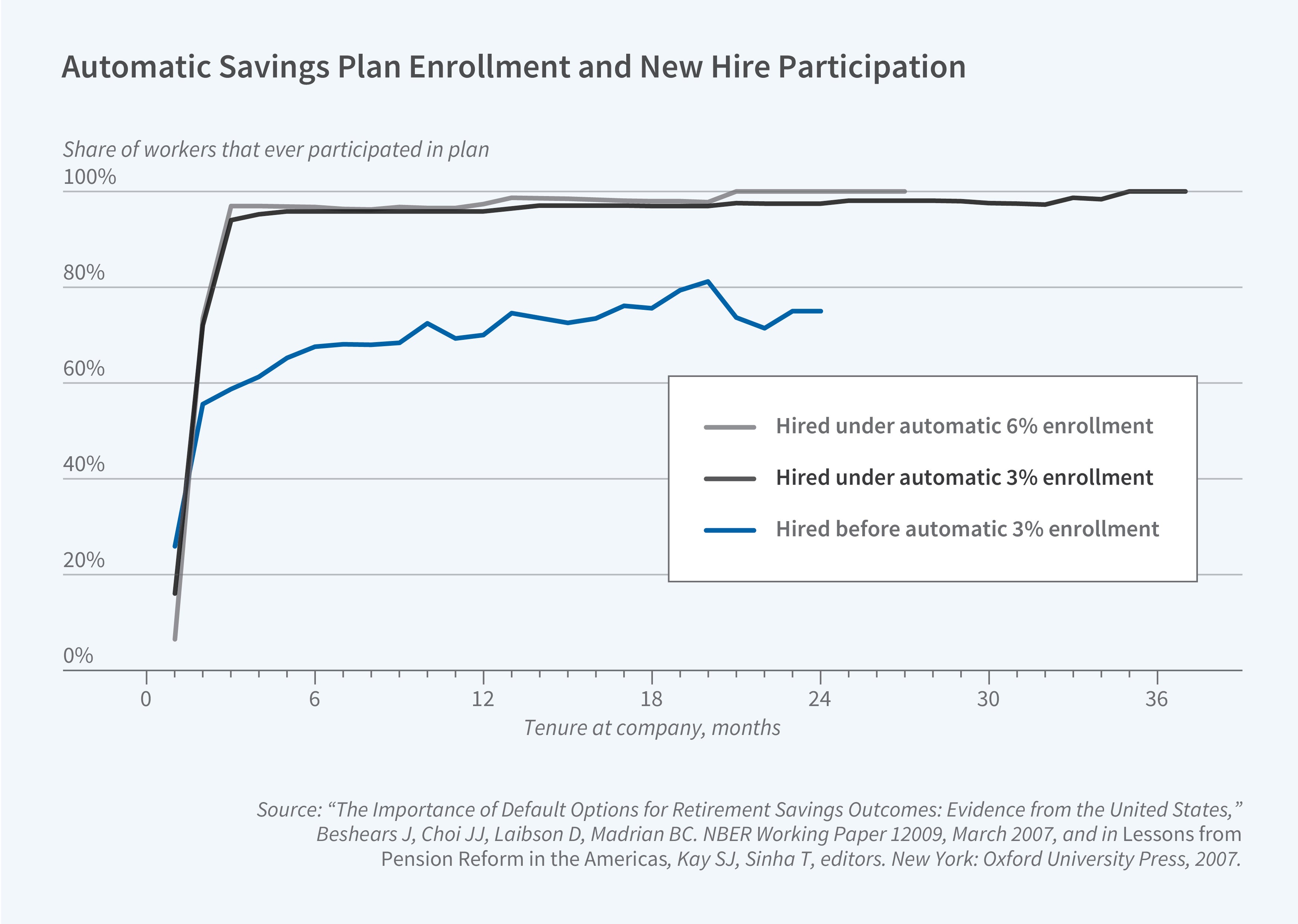

In a traditional opt-in DC plan, employees must proactively sign up to participate. In an automatic enrollment regime, employees are enrolled by default by their employer in the savings plan. They can always change their contribution rate or opt out entirely, but if they take no action, they will save the default percentage of gross pay from each paycheck — usually between 3 percent and 6 percent.6 In 2001, we analyzed the rollout of automatic enrollment at a large US corporation and found that it increased the percentage of employees who were participating in the 401(k) plan in tenure months 3–15 from 37 percent to 86 percent.7 We later corroborated these findings using data from other large employers and showed that automatic enrollment boosted 401(k) participation rates by 50 to 67 percentage points in tenure month 6, and by 31 to 34 percentage points in tenure month 36.8 Furthermore, the effect of automatic enrollment on the participation rate does not seem to depend on the exact default contribution rate — see Figure 1, which provides evidence from a company that instituted, at various points in time, an opt-in enrollment system, automatic enrollment at a 3 percent default contribution rate, and automatic enrollment at a 6 percent default contribution rate.9

The effect of automatic enrollment on participation is much larger than the effect of financial incentives in the form of employer contributions that match employee contributions to the 401(k). In a study of an employer that used automatic enrollment, we found that the plan participation rate dropped by 8 percentage points when the employer stopped offering a match.10

We have also documented the stickiness of default contribution rates and asset allocations in 401(k) plans. Our 2001 paper found that nearly two-thirds of automatically enrolled workers had not opted out, changed their contribution rate, or changed their asset allocation as of the time they were observed, some as early as after three months of tenure and others at 15 months of tenure.11 Similar patterns are present in other settings. For example, at the employer mentioned above that changed from a 3 percent to a 6 percent automatic enrollment default contribution rate, at 15–24 months of tenure the 3 percent default regime had 28 percent of employees at a 3 percent contribution rate and 24 percent of employees at a 6 percent rate (the lowest rate that earned the maximum employer matching contribution), whereas the 6 percent default regime had only 4 percent of employees at a 3 percent contribution rate and 49 percent of employees at a 6 percent rate.12

Automatic enrollment is a powerful device for shaping outcomes within a 401(k) plan, but it is important to note that the effect of automatic enrollment (relative to opt-in enrollment) on the mean employee contribution rate hinges on the magnitude of the default contribution rate. Automatic enrollment can increase the contribution rates of employees who otherwise would not have contributed at all or would have contributed at a rate lower than the default, but it can simultaneously decrease the contribution rates of employees who otherwise would have contributed more than the default. The net effect of automatic enrollment depends on the balance between these two forces.

Our early work on automatic enrollment helped to pave the way for legislative and regulatory changes. The Pension Protection Act of 2006 encourages employers to implement automatic enrollment in 401(k) plans as well as automatic escalation (a program of automatic annual contribution rate increases proposed and studied by Thaler and Benartzi13), and to make contingent (matching) or noncontingent contributions to employee accounts.14 In 2019, 40 percent of private sector workers participating in a 401(k) or similar plan were in a plan with an automatic enrollment feature.15 At the end of 2023, 59 percent of DC plans administered by Vanguard were using automatic enrollment.16 The SECURE 2.0 Act of 2022 requires most newly established 401(k) plans to implement automatic enrollment and default automatic escalation. Internationally, automatic enrollment has become a required feature of DC plans in Italy, Lithuania, New Zealand, Poland, Turkey, and the United Kingdom.

How Households Make Decisions: Procrastination and Complexity

A default specifies the outcome for employees who are passive. An alternative plan design, which we call active choice, does not allow employees to be passive: the employer requires each employee to actively indicate by a deadline the contribution rate they would like to implement.

We studied a large employer that changed its 401(k)-enrollment system from active choice to opt-in. Relative to opt-in, active choice resulted in a participation rate that was 28 percentage points higher in tenure month 3. Opt-in took two and a half years of tenure to attain the participation rate active choice achieved in three months.17

The fact that employees often choose to participate immediately when required to make an active choice but delay enrollment when allowed to be passive is consistent with the hypothesis that most employees believe they should save but procrastinate in enrolling in their 401(k). This mechanism also partially explains why employees often remain at the default option, and therefore why automatic enrollment has such a large impact on plan participation. Active choice, because it does not lead to herding at a single default, may be attractive to employers with highly heterogeneous employee populations, for whom choosing a universal default is particularly problematic.

In other work, we have documented that simplifying the 401(k) enrollment process can also increase saving. In opt-in enrollment, employees must take the initiative and decide how much to save and how to invest their savings.18 We designed and studied a mechanism called Quick Enrollment, which provides employees with a simplified enrollment form that enables them to check a box to enroll at a preselected contribution rate and investment allocation.

At two large employers, Quick Enrollment increased the 401(k) participation rate (among previously nonparticipating employees) by between 10 and 20 percentage points within three months of implementation.19 Subsequently, we found that Quick Enrollment was equally effective with a 2 percent, 3 percent, or 4 percent preselected contribution rate, and that a similar Easy Escalation treatment that allowed already-participating employees to increase their contribution rate to a preselected level was also effective.20

Effects of 401(k) Automatic Enrollment on Debt and Long-Term Asset Accumulation

Much of our research described above focused on how 401(k) plan design shapes employee outcomes within that 401(k) plan. In our recent work, we have taken a broader view and explored how other aspects of individuals’ finances and their long-run financial picture are affected.

Prior evidence documents that automatic enrollment increases 401(k) contributions, on average, provided that the default contribution rate is not too low. But how are these incremental contributions financed? One hypothesis is that savers decrease their spending. Another is that they take on additional debt.

We have evaluated the extent to which retirement savings induced by automatic enrollment are accompanied by increased debt in two separate contexts. We first studied the US Army’s introduction of automatic enrollment for new civilian hires in the Thrift Savings Plan (TSP), a federal government DC plan, at a 3 percent default contribution rate. For the first time, we were able to link employees’ retirement plan records to their credit files at a national credit bureau.

At tenure year 4, automatic enrollment increased cumulative TSP contributions by 4.1 percent of annual pay, with little evidence of attendant increases in financial distress. We did not find statistically significant changes in credit scores, adverse credit outcomes, or most types of debt. We did observe limited, weakly statistically significant increases in total balances on foreclosed first mortgages, but given the large number of hypotheses tested, this finding could be a false positive. Overall, this study suggested that 401(k) automatic enrollment has little to no negative credit effects.21

Our more recent work has added nuance to these initial findings. We examined the effect of automatic enrollment on debt outcomes in the context of the UK’s introduction of mandatory automatic enrollment in workplace pensions. We focused on a sample of employers with fewer than 30 employees because these employers were randomly assigned an automatic enrollment implementation date.

Exploiting this random variation, we estimated that each month of exposure to automatic enrollment (over the first 3.5 years) increased total pension contributions by £32–£38 and increased unsecured debt by £7, representing an 18 percent to 22 percent crowd-out of new retirement savings. This estimate is not inconsistent with our earlier work because it lies within the 95 percent confidence interval from our analysis of US Army civilian employees. However, the much larger sample size in our UK study allows us to reject the null hypothesis of zero increase of debt.

In the UK analysis, automatic enrollment also caused a modest increase in the average credit score and a decrease in loan defaults. At the same time, automatic enrollment increased employees’ likelihood of having a mortgage by 0.6 percentage points per year. The implications of this effect for employee net wealth are ambiguous because the addition of a mortgage to the employee balance sheet is accompanied by the addition of a home. In sum, the positive effect of automatic enrollment on retirement plan contributions is partially offset by an increase in unsecured debt.22

In another recent paper, we investigated the extent to which the effect of automatic enrollment on retirement wealth accumulation is undermined by a series of factors (other than increased debt) that have been underexamined in previous work. Figure 2 summarizes the key results.

In an analysis of four large employers, we found that a naïve extrapolation from the first year of employee tenure to estimate the long-run effect of automatic enrollment would erroneously lead to the conclusion that automatic enrollment increases the average rate of asset accumulation in the 401(k) by an equivalent of a 2.2 percentage point increase in the contribution rate. Incorporating data from the first five years of tenure into the calculation reduces the estimated effect to 1.8 percentage points because contribution rates under opt-in enrollment catch up with contribution rates under automatic enrollment as tenure increases. The estimated effect drops to 1.5 percentage points when we also account for the fact that plan rules often cause employees to forfeit a fraction of employer matching contributions if they depart the employer prior to reaching a specified tenure level. Finally, when we adjust our calculations to recognize that individuals often take withdrawals from their 401(k) when they separate from an employer (instead of leaving the balances in the 401(k) or rolling them over to another retirement savings account), the estimated effect of automatic enrollment is only a 0.6 percentage point increase in the contribution rate.

We find similar degrees of attenuation when we analyze the impact of default automatic contribution escalation.23

Conclusion

Automatic enrollment in 401(k) plans exerts a powerful influence on employee saving outcomes, but its positive average effect on plan contributions is partially offset by unsecured debt accumulation and preretirement withdrawals at employment separation, among other factors. These offsetting effects are not necessarily detrimental to employee wellbeing. For example, an employee separating from their employer may have a strong demand for liquidity to cover job transition expenses, implying that a preretirement withdrawal from their 401(k) is particularly valuable. However, policymakers looking to improve retirement security may nonetheless wish to counteract the forces that undermine the effect of automatic enrollment on wealth accumulation. For example, balances in the US DC retirement savings system are more liquid than those in substantial DC systems in other developed economies.24 Policymakers may consider (partially) disallowing preretirement 401(k) withdrawals under a wide range of circumstances to preserve retirement account balances25,26 while simultaneously encouraging the accumulation of savings earmarked for short-term liquidity needs, perhaps by promoting employer-based emergency savings accounts into which employees automatically contribute a percentage of their pay.27,28,29 These possibilities merit further study as employers, benefits providers, policymakers, and other stakeholders search for ways to improve individuals’ long-run financial security.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Sarah Holmes Berk for her major contributions to drafting this piece.

Endnotes

“Origins of the Three-Legged Stool Metaphor for Social Security,” DeWitte L. Research Note #1. Social Security Administration, May 1996.

“A Visual Depiction of the Shift from Defined Benefit (DB) to Defined Contribution (DC) Pension Plans in the Private Sector,” Myers EA, Topoleski JJ. Congressional Research Service, December 27, 2021.

“Retirement Assets Total $38.4 Trillion in Fourth Quarter 2023,” Investment Company Institute, 2024.

“The Importance of Social Security Benefits to the Income of the Aged Population,” Dushi I, Iams HM, Trenkamp B. Social Security Bulletin 77(2), 2017.

“Defined Contribution Pensions: Plan Rules, Participant Choices, and the Path of Least Resistance,” Choi JJ, Laibson D, Madrian BC, Metrick A. Tax Policy and the Economy 16, 2002, pp. 67–113.

“The Power of Suggestion: Inertia in 401(k) Participation and Savings Behavior,” Madrian BC, Shea DF. NBER Working Paper 7682, May 2000, and The Quarterly Journal of Economics 116(4), November 2001, pp. 1149–1187.

“Defined Contribution Pensions: Plan Rules, Participant Choices, and the Path of Least Resistance,” Choi JJ, Laibson D, Madrian BC, Metrick A. Tax Policy and the Economy 16, 2002, pp. 67–113.

“The Importance of Default Options for Retirement Savings Outcomes: Evidence from the United States,” Beshears J, Choi JJ, Laibson D, Madrian BC. NBER Working Paper 12009, March 2007, and in Lessons from Pension Reform in the Americas, Kay SJ, Sinha T, editors. New York: Oxford University Press, 2008. Also in Social Security Policy in a Changing Environment, Brown JR, Liebman JB, Wise DA, editors, pp. 167–195. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2009.

“The Impact of Employer Matching on Savings Plan Participation under Automatic Enrollment,” Beshears J, Choi JJ, Laibson D, Madrian BC. NBER Working Paper 13352, August 2007, and in Research Findings in the Economics of Aging, Wise DA, editor, pp. 311–327. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2010.

“The Power of Suggestion: Inertia in 401(k) Participation and Savings Behavior,” Madrian BC, Shea DF. NBER Working Paper 7682, May 2000, and The Quarterly Journal of Economics 116(4), November 2001, pp. 1149–1187.

“The Importance of Default Options for Retirement Savings Outcomes: Evidence from the United States,” Beshears J, Choi JJ, Laibson D, Madrian BC. NBER Working Paper 12009, March 2007, and in Lessons from Pension Reform in the Americas, Kay SJ, Sinha T, editors. New York: Oxford University Press, 2008. Also in Social Security Policy in a Changing Environment, Brown JR, Liebman JB, Wise DA, editors, pp. 167–195. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2009.

“Save More Tomorrow™: Using Behavioral Economics to Increase Employee Saving,” Thaler RH, Benartzi S. Journal of Public Economics 112(S1), February 2024, pp. S164–S187.

“Public Policy and Saving for Retirement: The ‘Autosave’ Features of the Pension Protection Act of 2006,” Beshears JB, Choi JJ, Laibson D, Madrian BC, Weller B. In Better Living Through Economics, Siegfried JJ, editor, pp. 274–290. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2010.

“How Do Retirement Plans for Private Industry and State and Local Government Workers Compare?” Zook D. Beyond the Numbers: Pay and Benefits 12(1), January 2023. Washington, DC: US Bureau of Labor Statistics.

“Optimal Defaults and Active Decisions” Carroll GD, Choi JJ, Laibson, Madrian B, Metrick A. NBER Working Paper 11074, January 2010, and Quarterly Journal of Economics 124(4), November 2009, pp. 1639–1674.

Investment decisions in general can be complex and challenging. For example, we have documented that investors often struggle to consider their whole portfolio when making investment decisions. See “Mental Accounting in Portfolio Choice: Evidence from a Flypaper Effect,” Choi JJ, Laibson D, Madrian BC. NBER Working Paper 13656, September 2009, and American Economic Review 99(5), December 2009, pp. 2085–2095.

“Reducing the Complexity Costs of 401(k) Participation through Quick Enrollment™,” Choi JC, Laibson D, Madrian B. NBER Working Paper 11979, January 2006, and in Developments in the Economics of Aging, Wise DA, editor, pp. 57–82. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2009.

“Simplification and Saving,” Beshears J, Choi JJ, Laibson D, Madrian BC. NBER Working Paper 12659, October 2006, and Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 95, 2013, pp. 130–145.

“Borrowing to Save? The Impact of Automatic Enrollment on Debt,” Beshears J, Choi JJ, Laibson D, Madrian BC, Skimmyhorn WL. NBER Working Paper 25876, July 2019, and Journal of Finance 77(1), February 2022, pp. 403–447.

“Does Pension Automatic Enrollment Increase Debt? Evidence from a Large-Scale Natural Experiment,” Beshears J, Blakstad M, Choi JJ, Firth C, Gathergood J, Laibson D, Botley R, Sheth JD, Sandbrook W, Stewart N. NBER Working Paper 32100, February 2024.

“Smaller than We Thought? The Effect of Automatic Savings Policies,” Choi JJ, Laibson D, Cammarota J, Lombardo R, Beshears J. NBER Working Paper 32828, August 2024. For a theoretical model demonstrating that present bias can simultaneously explain the large effect of automatic enrollment on initial contribution rates and large 401(k) withdrawals upon job separation, see “Present Bias Causes and Then Dissipates Auto-enrollment Savings Effects,” Beshears J, Choi JJ, Laibson D, Maxted P. AEA Papers and Proceedings 112, May 2022, pp. 136–141.

“Liquidity in Retirement Savings Systems: An International Comparison,” Beshears J, Choi JJ, Hurwitz J, Laibson D, Madrian BC. American Economic Review 105(5), May 2015, pp. 420–425.

“Optimal Illiquidity,” Beshears J, Choi JJ, Clayton C, Harris C, Laibson D, Madrian BC. NBER Working Paper 27459, July 2020.

“Self Control and Commitment: Can Decreasing the Liquidity of a Savings Account Increase Deposits?” Beshears J, Choi JJ, Harris C, Laibson D, Madrian BC, Sakong J. NBER Working Paper 21474, August 2015, and as “Which Early Withdraw Penalty Attracts the Most Deposits to a Commitment Savings Account?” Journal of Public Economics 183, March 2020, Article 104144.

“Building Emergency Savings through Employer-Sponsored Rainy-Day Savings Accounts,” Beshears J, Choi JJ, Iwry M, John D, Laibson D, Madrian BC. NBER Working Paper 26498, November 2019, and Tax Policy and the Economy 34, 2020, pp. 43–90.

“Employer-Based Short-Term Savings Accounts,” Berk SH, Beshears J, Garg J, Choi JJ, Laibson D. NBER Working Paper 32074, August 2024.

“Automating Short-Term Payroll Savings: Evidence from Two Large UK Experiments,” Berk SH, Choi JJ, Garg J, Beshears J, Laibson D. NBER Working Paper 32581, June 2024.