Workers Auto-enrolled in Pensions Save, but also Borrow, More

Many countries require employers to enroll their workers in retirement savings plans that deposit a regular percentage of their paycheck in a retirement account unless the worker opts out. These automatic enrollment programs are meant to address concerns that the employees, left to their own devices, might save too little for retirement. Previous research has documented that automatic enrollment in a savings plan significantly increases participation and contribution rates.

Automatic enrollment plans may, however, have unintended consequences. For example, reducing employees’ take-home pay might increase their borrowing, which could offset the benefits of increased retirement saving. The inertia harnessed by automatic enrollment, which helps induce high participation rates, might also lead workers to tap debt rather than reduce their spending to fund their additional pension contributions. Most studies of automatic enrollment have focused exclusively on the amount of money saved in workers’ retirement accounts because of data limitations. Researchers partnering with savings plan providers can observe inflows to retirement accounts, but they do not have any information on other financial flows or balances.

The average worker in the UK’s largest auto-enrollment plan saves an additional £32–38 per month, has an additional £7 of unsecured debt, and is more likely to have a mortgage.

In Does Pension Automatic Enrollment Increase Debt? Evidence from a Large-Scale Natural Experiment (NBER Working Paper 32100), John Beshears, Matthew Blakstad, James J. Choi, Christopher Firth, John Gathergood, David Laibson, Richard Notley, Jesal D. Sheth, Will Sandbrook, and Neil Stewart study data from the National Employment Savings Trust (Nest) in the United Kingdom. The UK Pensions Act 2008 required all firms to offer pensions with an automatic enrollment feature. Nest was created to support this pension rollout, and a large number of firms chose to create pensions through Nest. The researchers exploit randomized variation in the mandated automatic enrollment implementation date to investigate the effects of the policy. They link Nest pension accounts to workers’ credit reports, which allows them to study both saving and borrowing.

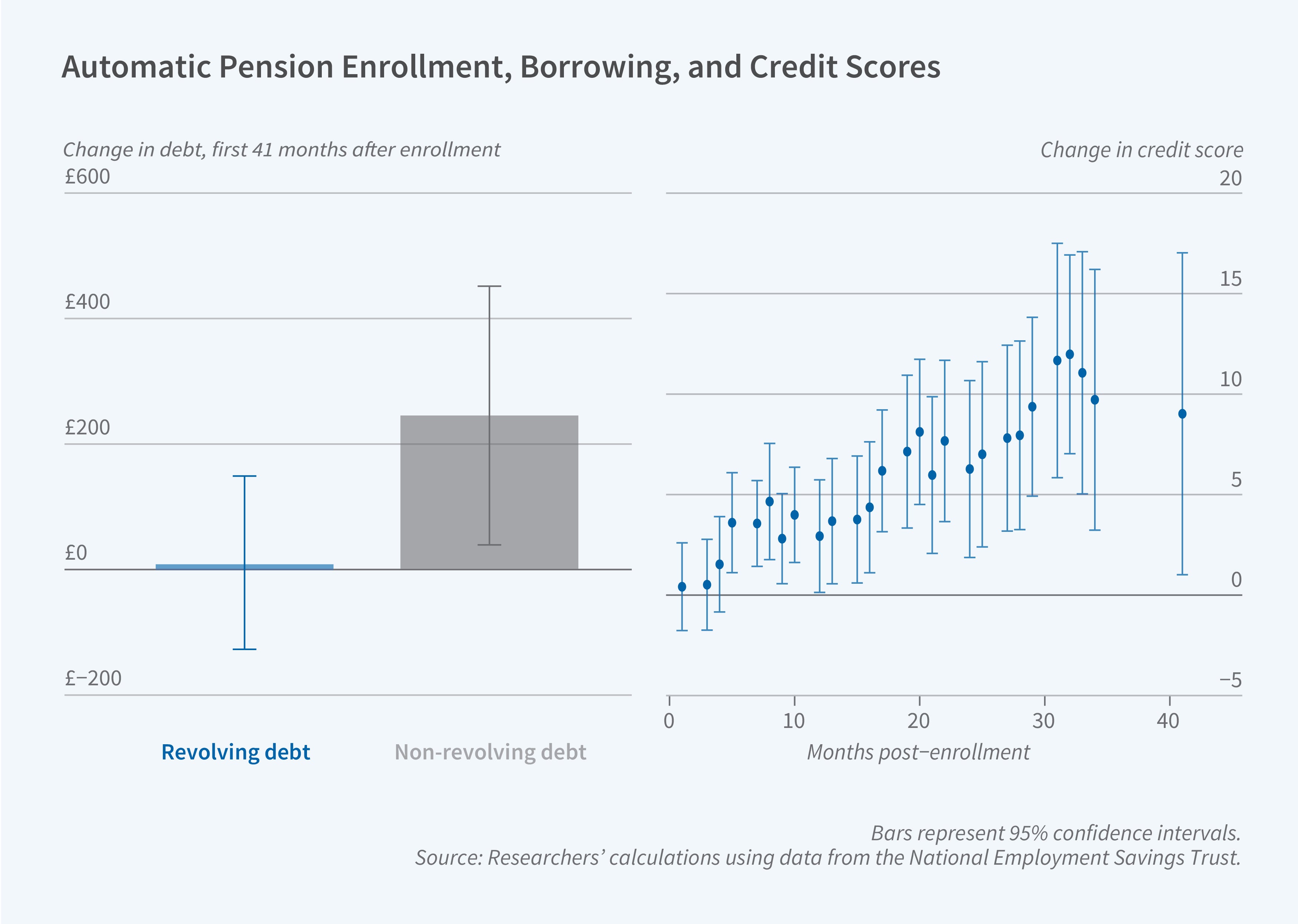

The researchers find that the average automatically enrolled worker saves an additional £32–£38 per month in the Nest pension, of which £13–£15 are contributions by the employee and the remainder are employer contributions and tax credits. But the average worker also takes on an additional £7 of unsecured debt. By four years after auto-enrollment began, enrolled workers were 1.9 percentage points more likely to have a mortgage. Although they took on more debt, enrolled workers experienced a 0.07 standard deviation increase in their credit score and a decline in the probability of defaulting on debt.

The researchers note that because automatic enrollees receive employer contributions and tax credits, taking on more debt may be a rational response to this injection of outside wealth, but it could also be the result of passively maintaining their pre-enrollment level of spending.

— Shakked Noy

The researchers acknowledge research support from the Blackrock Foundation, JPMorgan Chase Foundation, and the UK Money and Pensions Service. Researcher Beshears acknowledges further grant support from the National Institutes of Health, the Social Security Administration, the Smith Richardson Foundation, and the Pershing Square Foundation for Research on the Foundations of Human Behavior at Harvard University.