Foreclosures Can Amplify Downward Spirals of House Prices

Home mortgage defaults exclude defaulting households from the housing market and tighten capital constraints on lenders. Both effects push down home prices and create a potential role for policy.

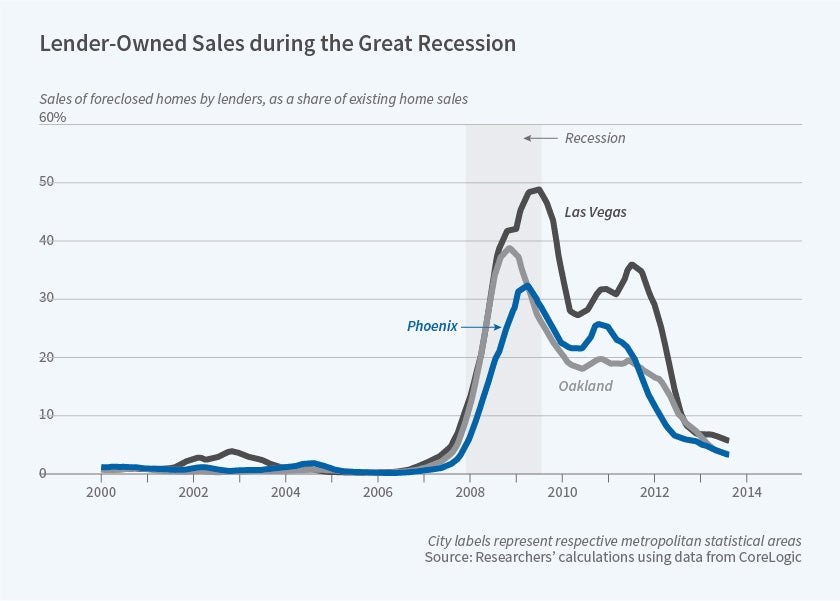

Between 2006 and 2013, mortgage lenders foreclosed on about 8 percent of the homeowners in the United States. Foreclosures play a complex role in housing market dynamics, and a number of policies that were adopted during the Great Recession were designed to lower the foreclosure rate.

In a new study of the co-movement of house prices and foreclosures, How Do Foreclosures Exacerbate Housing Downturns? (NBER Working Paper 26216), Adam M. Guren and Timothy J. McQuade explore how foreclosures magnify the impact of shocks to housing demand.

The researchers identify three channels through which foreclosures affect demand. First, buyers who default on their mortgages have a foreclosure flag placed on their credit record. This means that they are locked out of the housing market, because they cannot obtain another mortgage until this flag is cleared. Second, banks and other lenders face capital constraints, and when loans default these constraints become tighter. It is more difficult for lenders to extend new mortgages when they are more constrained. Finally, when distressed lenders sell foreclosed properties for less than they sell equivalent homes that are not in foreclosure in order to remove these properties from their books, recover part of their investment, and relax their capital constraints, remaining buyers become choosy and demand that other sellers, those who are not distressed, also lower prices.

When the housing market is hit by a shock that lowers housing demand and induces some foreclosures — for example a drop in employment — all three of these effects place further downward pressure on home prices and on the number of transactions in the housing market. The dynamic interactions between falling prices, defaults, and credit constraints keep growing numbers of buyers out of the market. The scarcity of buyers lowers prices, intensifies the buyers’ market, and leads to a downward price-default spiral.

To quantify the effect of foreclosure-related factors on the housing market, the researchers construct a model of the US housing market and calibrate it using data for the 2006-13 period. They analyze monthly data provided by CoreLogic for 99 of the 100 largest core-based statistical areas. Across cities, they find that the size of the preceding local housing boom was the best predictor of the size of the next local bust. But cities with a larger boom — and more foreclosures in the bust — had a more-than-proportionately larger bust, which the model attributes to price-default spirals.

The researchers estimate that foreclosure-related dynamics played a key role in the decline in non-foreclosure house prices in their sample period. They attribute 22 percent of the drop to a substantial number of potential home buyers being excluded from the market because of bad credit associated with past foreclosure flags. Lender rationing — the effect of tighter credit constraints on financial institutions — can account for another 23 percent of the price decline, and for a larger share, about 40 percent, of the decline in home sales. The “choosey buyer effect” contributed another 3 percent to the price decline. Persistent declines in home valuations account for the remaining 52 percent, implying significant overshooting due to foreclosures.

The researchers also study how various policy interventions might have slowed the rate of foreclosures and the decline in house prices. Such interventions have the greatest benefit when shocks to housing demand are transitory. By allowing borrowers time to become current on their loans, these policies reduce the overall foreclosure rate.

A government policy of injecting cash or equity equal to 50 percent of bank losses would have reduced foreclosures by 19.3 percent and price declines by 23.9 percent at a cost of $2,175 per household. Reducing principal with a $10,000 payment up to a loan-to-value ratio of 115 percent would have reduced defaults by 16.4 percent and price declines by 10.5 percent at a cost of $1,917. Had the government purchased foreclosed homes and sold them after a year, reducing both foreclosures and lender credit rationing, the number of foreclosures would have declined by 40.3 percent and price declines would have been reduced by 44.8 percent at a cost of $2,150 per household, the researchers conclude. The analysis indicates that the most cost-effective policies directly address the imbalance of supply and demand in the market.

— Linda Gorman