Labor Market Returns from International Migration

The international migration of skilled workers can bring needed talent to developed nations, but it has also been labeled “brain drain” in the countries these workers leave. In Return Migration and Human Capital Flows (NBER Working Paper 32352), Naser Amanzadeh, Amir Kermani, and Timothy McQuade provide new evidence on the labor market returns to international migration from the perspective of skilled workers.

The researchers analyze data on employment and education histories from Revelio Labs, which gathers information from public LinkedIn profiles and other sources. The dataset consists of more than 450 million profiles of workers in over 180 countries. In many cases, the worker’s posting includes a country location. For many of those that do not, the researchers impute the employment location based on employer data. They combine the Revelio data with firm and position-level salary data from Glassdoor.

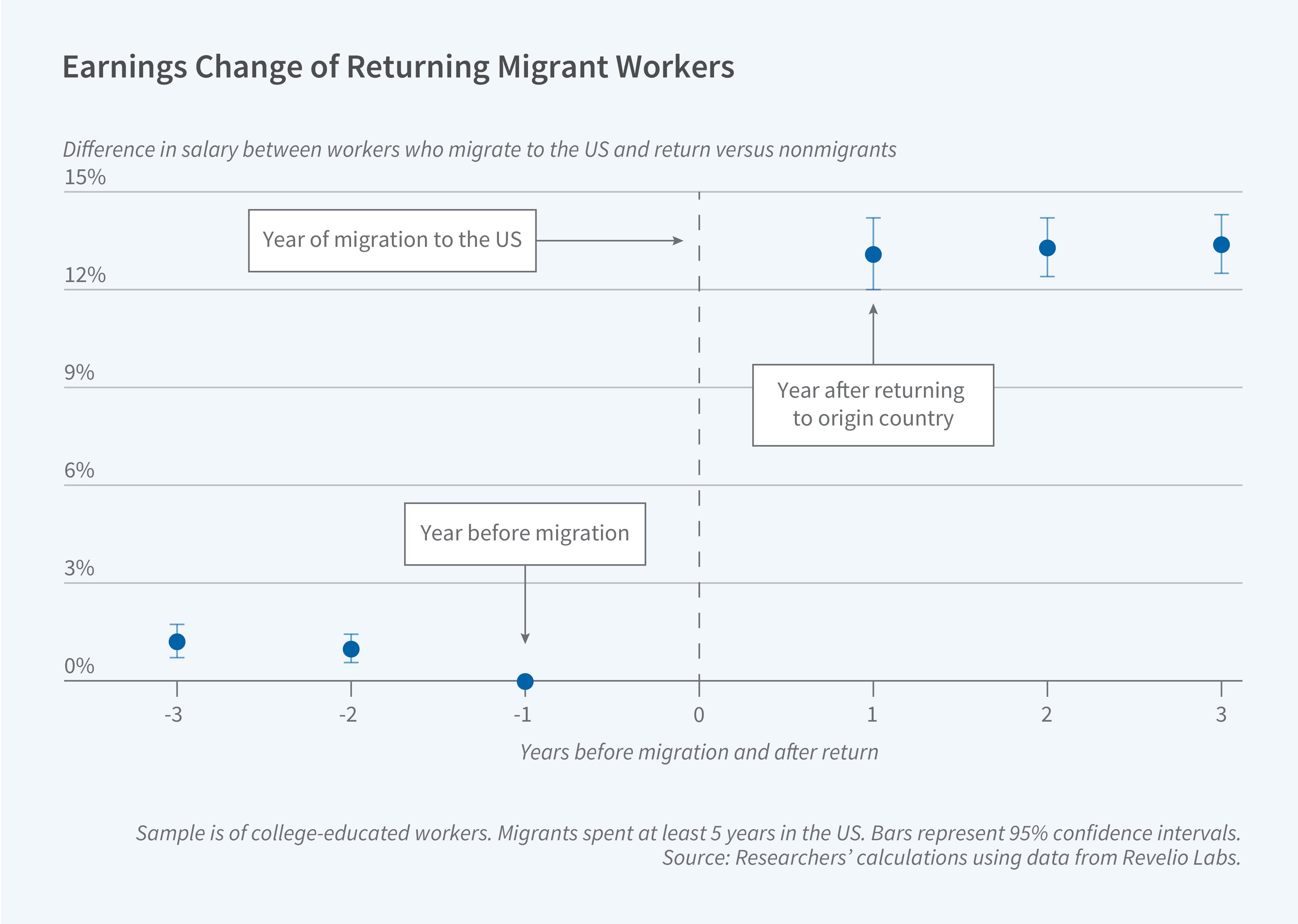

The annual wage increase from a year of employment for an average worker with 10 years of experience is at least 60 percent higher if that year is worked in the US rather than at home.

The dataset provides interesting evidence on migration patterns. On average, 3.4 percent of skilled laborers migrate during a five-year period. Higher-skill workers are more likely to migrate, especially in emerging markets. Out-migration rates vary substantially among different countries, being below the global average in the US and China and above it in Germany and India. About one-third of those who migrate are employed by multinational firms in their destination country, and about one in eight of this group were previously employed by the same firm in their home country.

Ten percent of migrants return to their home country within a year, and 33 percent return within five years. A decade after leaving their home country, half have remained in the host country they first moved to, 12 percent have moved to a third country, and 38 percent have returned to their country of origin. Return rates differ substantially by country, with higher return rates in advanced economies and some emerging market economies like Chile and Indonesia. India has a relatively low return migration rate.

Some similarities are evident in migration patterns. Migrants tend to move to countries with higher per capita GDP, and they display a preference for closer destinations and for countries that speak the same language as their home country. Originating from a higher GDP per capita country and sharing a language with the destination country increases workers’ likelihood of returning to their country of origin. Industry growth also affects migration choices, with return migration increasing with growth in a worker’s industry and adjacent industries in the origin country, and decreasing with growth in that industry and adjacent industries in the destination country.

A given worker’s wage can be decomposed into a component due to work location, a component due to the worker’s skills, and a component due to labor market experience. On average, a worker in an emerging market with 10 years of experience who gains an additional year of experience in the home country sees a wage increase of about 1 to 1.8 percent. If, instead, the same worker acquires another year of experience in the US, her wage increase upon her return is about 2.8 percent.

The researchers also study the returns to migrating for education. In emerging markets, an additional year of education at a school ranked in the top 50 globally is associated with a wage increase roughly twice as large as the increase from an additional year in a school not ranked in the top 1,000 globally. The relationship between schooling and wages is weaker in advanced economies outside the US and there is less spread in the wages earned by graduates of higher- and lower-ranked schools than in developing nations.

—Whitney Zhang

This work was supported by the Fisher Center for Real Estate and Urban Economics and the Clausen Center for International Business & Policy at University of California, Berkeley.