Are Investors Inattentive to SEC-Mandated Corporate Reports?

A six-fold increase in the length of 10-Ks since 1995 has made much new information available to investors, but stock prices seem unresponsive to some potentially significant disclosures.

Financial market prices move on information. Changing regulations as well as corporate reporting norms have increased the amount of information available to investors, raising questions about the capacity of investors to process it. By 2014, for example, 10-K reports were more than six times longer than in 1995. Are investors more likely to miss useful information as the volume of required disclosures increases?

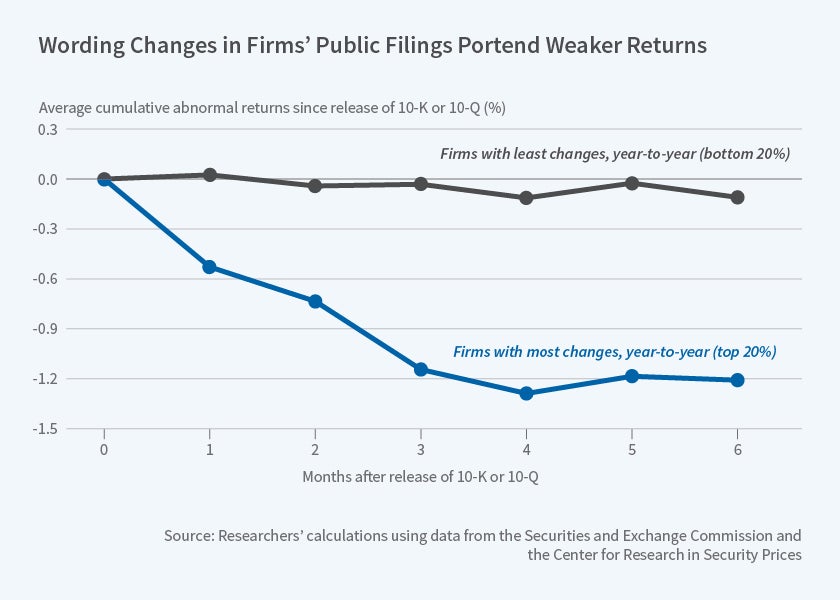

In Lazy Prices (NBER Working Paper No. 25084) Lauren Cohen, Christopher Malloy, and Quoc Nguyen study the language and construction of all financial reports required by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) for publicly traded firms in the United States over the two decades beginning in 1995. They construct portfolios of firms that had few textual changes in quarter-to-quarter reports and firms that had many changes, and find that portfolios that were long "non-changers" and short "changers" earned a statistically significant value-weighted abnormal return of between 34 and 58 basis points per month—between 4 and 7 percent per year—over the following year.

The abnormal returns continued to accrue for up to 18 months after the date of the regulatory filing and they were not reversed subsequently. They were not related to firm size, time, industry, or one-time firm events. The authors conclude that changes in the language used in the reports contained important new information for investors, information that was gradually incorporated into asset prices. They suggest that the excess returns occur because investors failed to recognize the systematic and rich information contained in simple changes to a firm’s annual reports.

To quantify changes to firms' annual reports, the researchers compare quarter-to-quarter similarities between 10-Q and 10-K textual content using four different measures of similarity. Two of these measures compare the frequency of terms in the documents. A third counts the smallest number of operations needed to transform one document into the other. For example, changing "We expect demand to increase" from one year's filing into the next year's "we expect worldwide demand to increase" requires adding "worldwide" to the first sentence and counts as a single operation. The fourth similarity measure uses word processor document-comparison software to show changes in the two documents. The measure counts the number of words added or deleted and divides by the total number of words.

While changes in the wording of the management discussion section of company reports did predict large and significant abnormal returns, textual changes in the risk factors section were even more informative, predicting abnormal returns of 188 basis points per month, or over 22 percent per year. Also important were changes in language that pertained to the CEO or CFO, changes related to litigation and lawsuits, and increased use of words freighted with negative sentiment. More than 86 percent of changes were "negative sentiment" changes. This may suggest that the success of class-action lawsuits alleging underreporting of adverse information encouraged firms to report potentially negative material information to a disproportionate degree. The 14 percent of changes that represented positive sentiment were significant predictors of positive future abnormal returns.

To examine investors's actions in greater depth, the researchers filed a Freedom of Information Act request for data that gave them the date and time each report was downloaded from the Securities and Exchange Commission's EDGAR website, as well as the downloader's IP address. The short-run announcement effects on stock prices were more pronounced when investors were downloading the current and prior year's 10-K at the same time. The researchers assume that dual downloading means that investors paid more attention to textual changes from one year to another, and conclude that when investors are focusing on changes from one filing to the next, information is incorporated more rapidly into stock prices. The subsequent abnormal returns are smaller when there was more dual downloading at the time of the SEC filing.

— Linda Gorman