Property Tax Assessments vs Market Values

Property taxes represent the largest discretionary revenue source for local governments in the United States. Because these taxes are collected by applying a tax rate to an assessed value of a property, the effective tax rate on a property — computed as a percentage of its value — depends on the tax rate and on the relationship between the property’s assessed and market values. Although every state requires local governments to capture market fluctuations in their property assessments, they may not do so in a timely or effective fashion.

In Assessing Assessors (NBER Working Paper 33238), researchers Huaizhi Chen and Lauren Cohen analyze a comprehensive dataset of US property tax assessments and housing transactions between 2000 and 2020. They combine county-level census data on property tax revenues, property assessments, and transactions from the Zillow Transaction and Assessment Database with hand-collected data on tax assessors’ identities and property holdings.

Property tax assessments in the US often deviate from market values and tend to adjust in ways that stabilize municipal revenues.

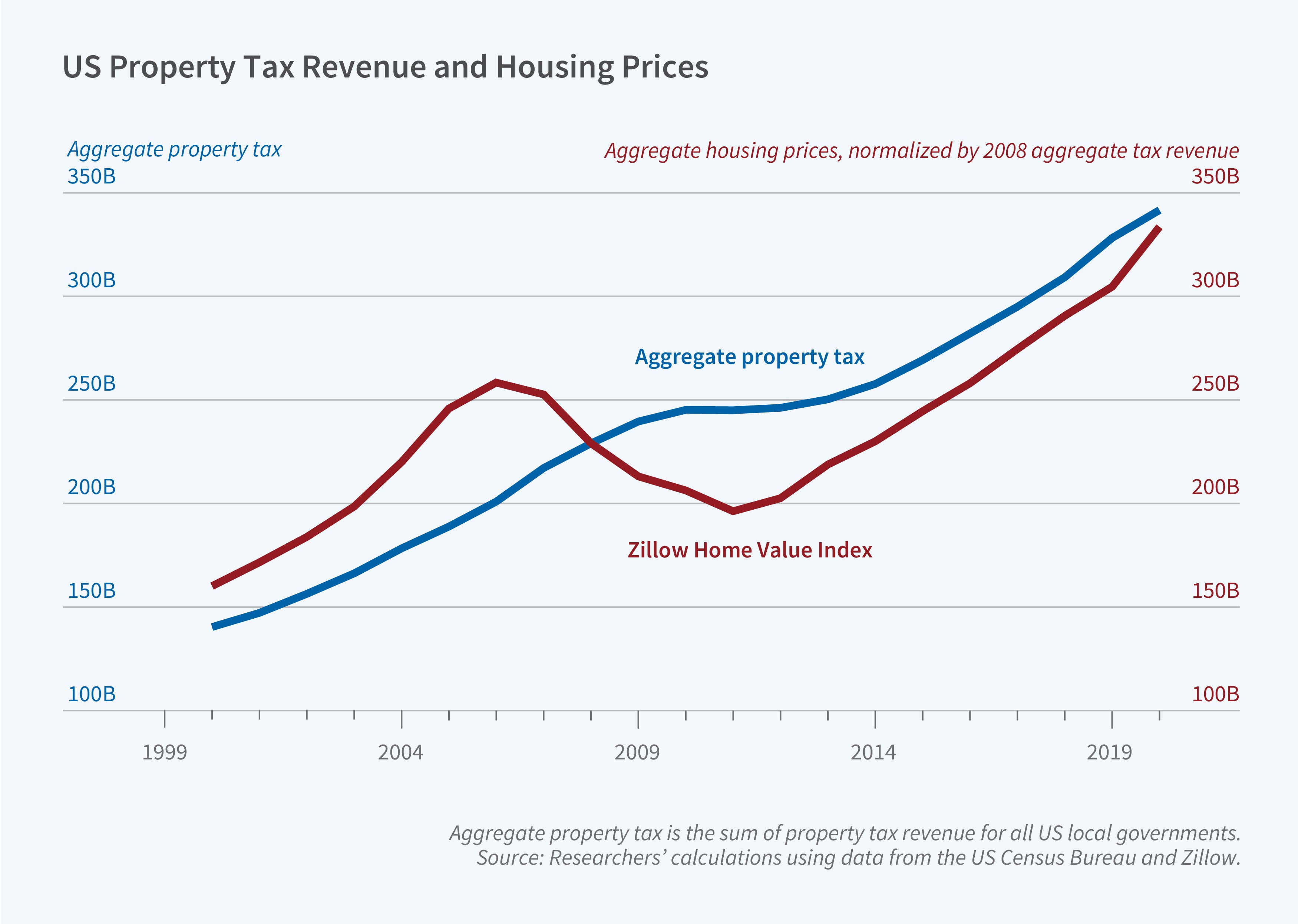

The researchers find that property tax revenues are stable even during periods of significant real estate market volatility. On average, a 1 percent change in the market value of properties in a jurisdiction results in less than a 0.30 percent change in assessed values in the next three years. The change in market values over the current and previous two years explains only about 8 percent of the variation in assessment growth. This disconnect appears strategic rather than incidental as counties are significantly more likely to reassess properties upward during market growth than to reduce assessments during a downturn. Furthermore, changes in total property tax revenue correlate more strongly with changes in local per-capita income than with property market returns, with income elasticity approximately three times larger than market price elasticity.

Counties with higher budget deficits show higher assessments relative to market values, a finding that is consistent with the use of assessments to generate revenue. A 10 percent increase in county-level expenses relative to revenue is associated with assessments about 10 percent higher relative to housing transaction prices. Changes in tax rates are also associated with waves of reassessment. Using data from Illinois, the researchers find that between 2006 and 2014, passing a school referendum — which typically raises tax rates — leads to a 23 percent increase in the probability of upward property reassessments without corresponding increases in actual market values.

The research also uncovers patterns in how tax assessors treat their own properties. Their assessments grow at about a 1 percent lower annual rate than the average in their jurisdiction and about 0.7 percentage points slower than assessments of neighboring properties. This disparity is larger when the assessor tends to overvalue other properties in their jurisdiction.

— Leonardo Vasquez