Creation of the Euro and Productivity Growth in Southern Europe

Falling real interest rates in the south following the adoption of a common currency triggered an influx of capital, but the capital did not necessarily flow to the most productive firms.

A possible explanation for the divergence in productivity growth between northern and southern Europe since the adoption of the euro in 1999 is that capital inflows to the south were allocated inefficiently by the region's less-developed financial markets. Gita Gopinath, Sebnem Kalemli-Ozcan, Loukas Karabarbounis, and Carolina Villegas-Sanchez explore this theory in Capital Allocation and Productivity in South Europe (NBER Working Paper 21453).

"We show that the cross-sectional correlation between capital and firms' productivity decreased over time," they write. "This suggests that capital inflows were increasingly directed toward less productive firms." They present an economic model in which firms face transitory idiosyncratic productivity shocks and there are borrowing constraints that keep smaller firms from taking out loans. They demonstrate that a decline in real interest rates can trigger a huge influx of capital which goes to the largest, but not necessarily the most productive, companies.

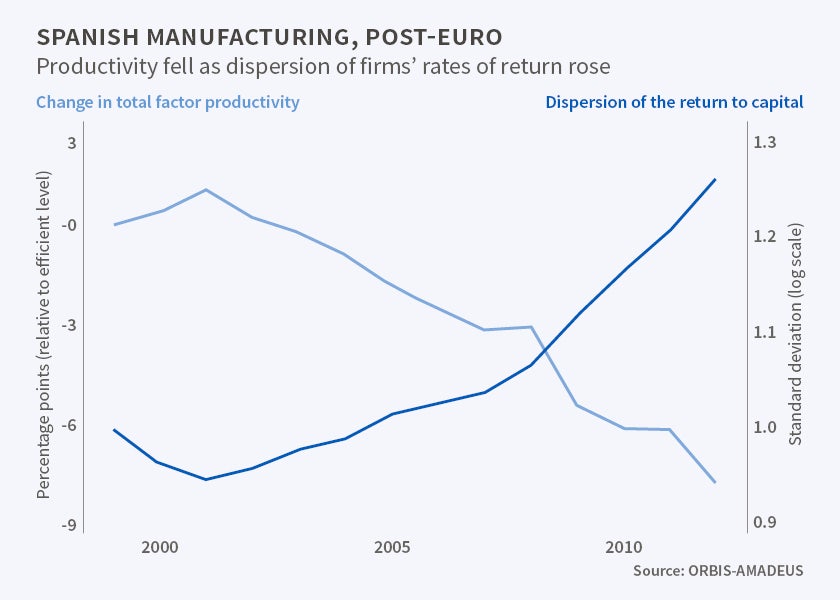

Using a firm-level dataset covering roughly 75 percent of the Spanish manufacturing sector, the authors find that the standard deviation of the firms' return on capital rose between 1999 and 2012. This dispersion was clear prior to the financial crisis; it accelerated in the post-crisis period. In the meantime, the standard deviation of the return on labor hardly changed at all.

"The striking difference between the evolution of the two dispersion measures argues against the importance of changing distortions that affect both capital and labor at the same time," the authors write. "For example, this finding is not consistent with heterogeneity in price markups driving trends in dispersion."

When the euro was created in 1999, countries that adopted it needed to initiate policies that would help the nations in the eurozone to converge. One result of these efforts was that real interest rates began to fall for southern Europe, which in turn triggered an influx of capital. The authors suggest that as the cost of borrowing fell, larger firms increased their investment, and experienced a falling return on capital, while smaller firms that could not borrow, and that relied on internally-generated funds for investment, invested less and did not experience declining returns.

The authors suggest that as a result of falling real interest rates, "capital flows into the [manufacturing] sector, but not necessarily to the most productive firms, which generates a decline in sectoral TFP [total factor productivity]."

The study also examines data from Italy, Portugal, Germany, France, and Norway. Both southern European nations – Italy and Portugal – experienced an increase in the dispersion of the return to capital similar to Spain's, while France, Germany, and Norway did not. The southern countries also experienced much slower growth of total factor productivity than the northern countries. This is consistent with less-well-developed capital markets in the south impeding the efficient allocation of capital.

—Laurent Belsie