India's Demonetization Reduced Employment and Economic Activity

Declines in employment, output, and credit occurred when cash suddenly was in short supply due to a government anticorruption effort.

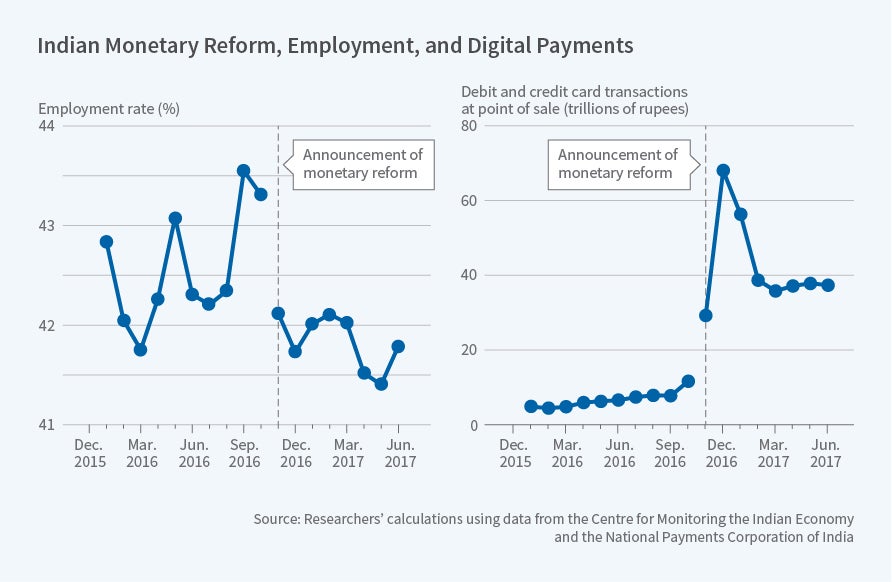

Cash still matters in India. In the fourth quarter of 2016, a sudden, temporary, and almost complete disappearance of large-denomination bills caused a decline in the quarterly growth rate (not annualized) of employment, economic output, and in bank credit of 2 percentage points, according to a study by Gabriel Chodorow-Reich, Gita Gopinath, Prachi Mishra, and Abhinav Narayanan. The Indian experience therefore rejects the view that in a modern economy the interest rate is all that matters and the availability of paper money is of little consequence.

"In modern India cash serves an essential role facilitating economic activity," the researchers conclude in Cash and the Economy: Evidence from India's Demonetization (NBER Working Paper 25370).

In an attempt to stem corruption and counterfeiting, the Indian government made an unexpected announcement on November 8, 2016, declaring it illegal to use 500 and 1,000 rupee notes as legal tender. The popular notes, worth $7.50 and $15, respectively, represented 86 percent of the cash in circulation. Residents had until December 31 to deposit their notes into their bank accounts. After depositing the old notes, they could withdraw funds in new 500 or 2,000 rupee notes.

The government was slow to produce and distribute the replacement bills, which caused a temporary but sharp cash squeeze. Using data on the geographic distribution of the new notes, the researchers find that in December 2016 the value of the new notes in circulation in the median geographic district amounted to only 31 percent of the value of the old notes in circulation before November 8. That percentage varied greatly by region. The district at the 90th percentile had received 64 percent of the value of its old bills in new notes, while in the one at the 10th percentile only 13 percent of old notes had been replaced. The significant cross-district disparities enabled the researchers to study the consequences of demonetization using geographic variation in the value of notes replaced.

Hard-hit districts, those with a sharper fall-off in currency in circulation, saw a sharper fall-off in economic activity as measured using a household survey of employment and satellite data on human-generated nighttime light. At its peak, demonetization had roughly the same impact on economic output as researchers have estimated that a 200 basis point tightening of the federal funds rate would have on U.S. economic activity.

The researchers note that while economic activity fell, the output decline was an order of magnitude smaller than the decline in cash itself. They conclude that households adjusted to the lack of cash by using other forms of payment or even informal lines of credit to make purchases. Between October and December 2016, transactions using an Indian e-wallet technology doubled. The increase was even more in harder hit districts. Credit- and debit-card transactions using point-of-sale systems also increased substantially.

The impact of the cash shortage was temporary. The researchers estimate that demonetization reduced economic activity in India by at least 3 percentage points in November and December 2016, but the effects began to dissipate in the following months. By March 2017, new bills in circulation in the median district represented 77 percent of the value of the old currency, and by June 2017 the shortage was mostly over.

— Laurent Belsie