Fear of Failure, Bank Panics, and the Great Depression

Analysis of new data from the early 1930s suggests that depositors’ fears led to runs on banks that were clustered in time and space. These panics significantly reduced lending and monetary aggregates.

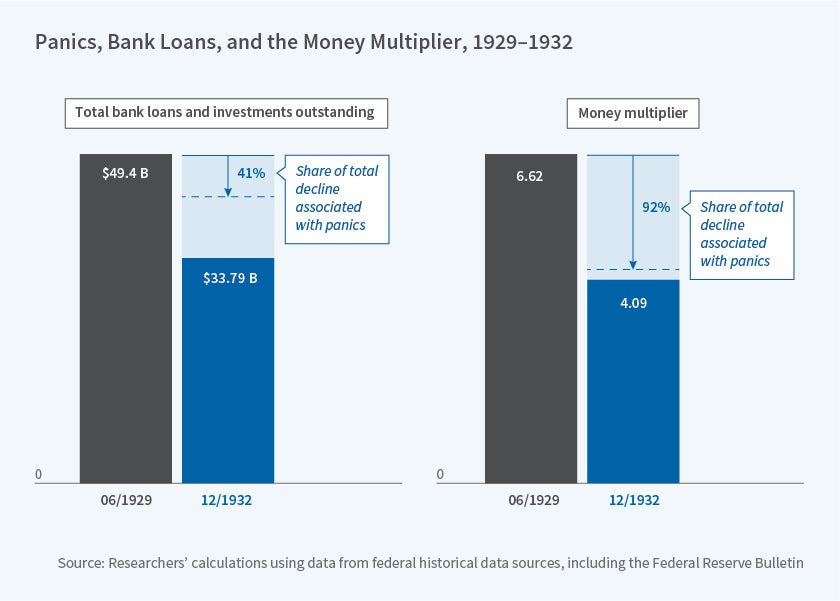

Between 1929 and 1932, the money supply and bank lending in the United States declined by more than 30 percent. In Contagion of Fear (NBER Working Paper 26859), Kris James Mitchener and Gary Richardson attribute much of this decline to the changing behavior of bank depositors. In 1930, after the collapse of Caldwell and Company, the largest bank-holding company in the South, runs on banks became widespread. The calling card of a panic, according to contemporaries, was the suspension of numerous banks in close proximity in a short period, such as within ten miles and 30 days. These panics deprived banks of deposits, which forced them to adjust their balance sheets and reduce lending to businesses and households. These declines in deposits and increases in reserves account for almost all of the decline in the money supply during the Great Depression.

The researchers assemble a new set of data on bank balance sheets, loans, deposits, and reserves as well as currency in circulation at the Federal Reserve district level, most of which was originally published in the Federal Reserve Bulletin. The data allow them to calculate the money supply in each Fed district at call dates, roughly quarterly. They compare this new data to microdata on bank failures gathered from the archives of the Fed.

The data demonstrate that the average number of weekly bank suspensions doubled after Caldwell’s failure in the fall of 1930, rising from 15.1 to 39.1. Panic-induced bank closures peaked in the last quarter of 1930 and in the last two quarters of 1931. Among the bank suspensions that occurred during panics, about 55 percent were associated with large regional or national events, while the remainder were due to local conditions.

The researchers find that when banks failed during periods that were not classified as panics, there was usually a “flight to quality,” with deposits flowing to Federal Reserve member banks; these banks were likely seen as more stable than non-member banks. During panics, however, the reverse was true, and deposits flowed out of the banking system, even from Fed member banks. These outflows were associated with reduced lending, although the magnitude of the effect varied by place. For each dollar that flowed out of a Federal Reserve System member bank in New York or Chicago, the two central reserve cities, business loans declined by an estimated 35 cents. By comparison, a dollar flowing out of a member bank in another city on average reduced lending by 54 cents. At non-member banks, a one-dollar deposit outflow was associated with a 51-cent decline in loans.

Combining microeconomic data on individual bank suspensions with these econometric estimates allows the researchers to calculate the aggregate impact of panics on economy-wide lending. Their findings indicate that banking panics reduced lending in banks that remained in operation by $6.4 billion, nearly twice the $3.3 billion in loans and investments trapped in failed banks. Keeping the money supply constant at the pre-Depression level would have required a 60 percent expansion in the monetary base. This expansion would have been feasible, given resources available to the Fed at the time, and would not have seemed unreasonable in the decades after the Depression. It was, for example, only one-third as large as the 200 percent expansion in the monetary base that policymakers enacted following the failure of Lehman Brothers in 2008. The researchers note that their findings underscore the importance of bank balance sheets in both downturns and recoveries.

— Linda Gorman