Why So Many Investors Believe Trouble Lies Ahead

The prevalence of attention in financial media to adverse market outcomes is correlated with investor crash beliefs.

Investors' beliefs about whether a severe market crash is impending can affect the prices and prospective returns on risky assets, such as publicly traded stocks. However, beliefs regarding extreme market events are difficult to measure using typical economic data, precisely because they are low-probability outcomes. Observed asset prices are also determined by investor preferences, such as their degree of risk tolerance, as well as by beliefs about future outcomes.

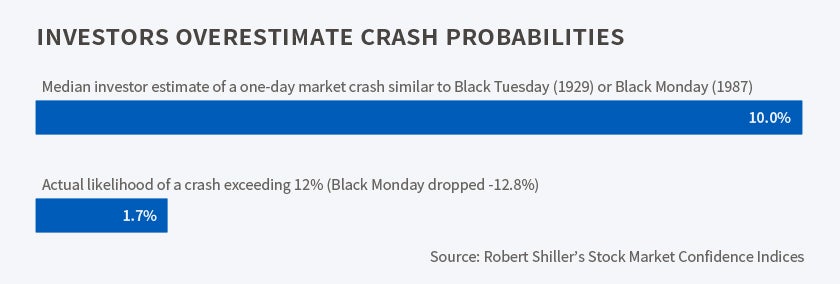

In Crash Beliefs from Investor Surveys, (NBER Working Paper 22143), William N. Goetzmann, Dasol Kim, and Robert J. Shiller provide direct evidence using surveys that capture investor beliefs regarding stock market crashes between 1989 and 2015. The researchers find that investors routinely overestimate the likelihood of severe crashes.

When asked about the probability of a crash similar to that on Black Tuesday (October 29, 1929) or Black Monday (October 19, 1987) occurring in the next six months, the median response was a probability of 10 percent. Historical data from 1929 to 1988, however, indicate that the likelihood of such a crash is only 1.7 percent.

The researchers investigate behavioral channels that could contribute to this phenomenon by examining whether investor crash beliefs are subject to media influence. They show that stock market downturns are more likely to be reported in financial media than upswings. They posit that the results are consistent with investors exhibiting "availability bias," or that investors assign greater weight to "top-of-mind" information.

The researchers find that investors use recent stock market performance to estimate their crash probabilities. Media coverage makes the effects of market downturns on crash beliefs more salient, particularly for non-professional investors. In addition, they provide consistent evidence of the influence of behavioral mechanisms using other rare events that are unrelated to stock market activity, such as earthquakes.

The research findings add to a large literature on the ways in which financial decision-making may deviate from textbook models of rational choice. The findings may help to inform other areas where rare disaster concerns are relevant, including the long-standing equity premium puzzle, time-varying market premiums, and the so-called volatility smile.

—Andrew Whitten