Eliminating 'Food Deserts' Won't Cure Nutritional Inequality

Exposing low-income households to the same food-buying opportunities available to higher-income households would reduce nutritional inequality by only 9 percent.

Low-income households consume less nutritious diets than their high-income counterparts. Of the many potential explanations, one that has attracted recent attention among policy advocates argues that a substantial fraction of the poor live in "food deserts," neighborhoods lacking full-service supermarkets stocking a wide variety of healthy foods.

In Geography of Poverty and Nutrition: Food Deserts and Food Choices Across the United States (NBER Working Paper No. 24094), Hunt Allcott, Rebecca Diamond, and Jean-Pierre Dubé find that nutritional inequality has less to do with the supply of supermarkets in a neighborhood than with the demand for healthier foods by its residents. Their findings suggest that education, nutritional knowledge, and regional food preferences play a far larger role in nutritional inequality than access issues.

This study analyzes what people of varying incomes eat and drink, measures the nutritional value of their consumption, and assesses the role that food deserts play in nutritional inequality. The researchers rely on data from a wide variety of sources which provide them with a rich array of demographic and geographic information about who buys what, where stores are located, where purchasers live and shop, and even when new food stores open in neighborhoods.

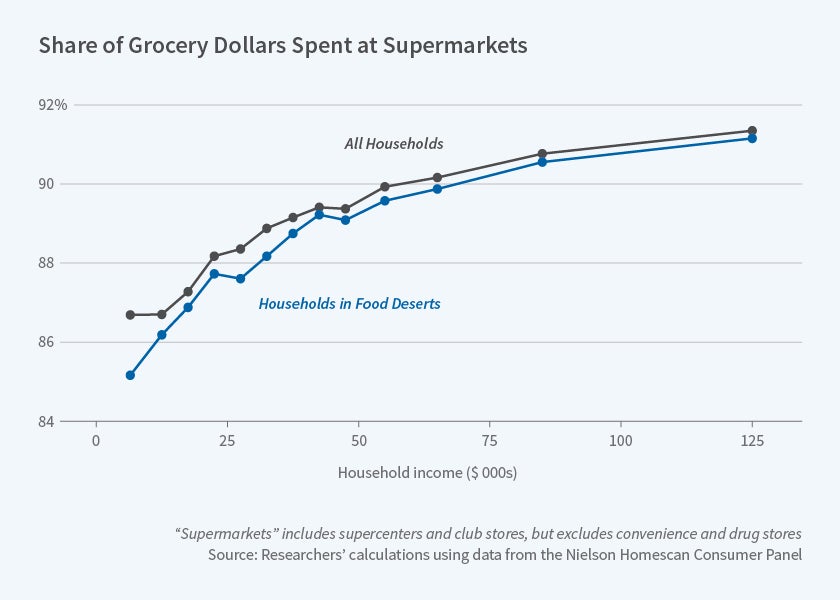

They find differences in the availability of supermarkets in higher-income and lower-income neighborhoods, with higher-income districts having larger food stores clearly capable of stocking a wider variety of produce, breads, meats, dairy products, and other goods than the more limited offerings of smaller corner grocery and drug stores common in lower-income areas. The researchers also confirm that those in higher-income areas buy more healthy and nutritious foods in general. So there is a correlation between food deserts and poor nutritional outcomes.

But the researchers also examine what happens after the opening of new supermarkets in low-income neighborhoods that were previously identified as food deserts, and what happens when individuals move from low-income areas to higher-income areas where there are more supermarkets with a wider variety of healthy foods. They find that the entry of new supermarkets has only a limited effect on shoppers' purchasing patterns, and that variation in access to supermarkets accounts for only about 5 percent of the difference in healthy eating between high-income and low-income households.

Purchasing and geographic data help to explain this finding. Those who live in food deserts drive longer distances to get food at supermarkets, so when new supermarkets open in their own neighborhoods, they merely transfer their old purchasing habits to the new stores. They benefit when new stores open in their neighborhoods, but those benefits are mostly tied to a reduction in their travel time and transportation costs of buying food.

The research finds that those who move to areas where others generally eat more healthy foods do not change their own eating patterns, at least over the several-year time horizon studied. The researchers conclude that exposing low-income households to the same food-buying opportunities and prices that are available to higher-income households would reduce nutritional inequality by only 9 percent; the remaining 91 percent is due to differences in demand.

— Jay Fitzgerald