How Higher Ed and Immigration Policies Affect the Level of Foreign IT Workers

Student visas allow workers to enter the U.S., obtain a degree, and transition to a work visa, an alternative to trying to obtaining scarce temporary work visas.

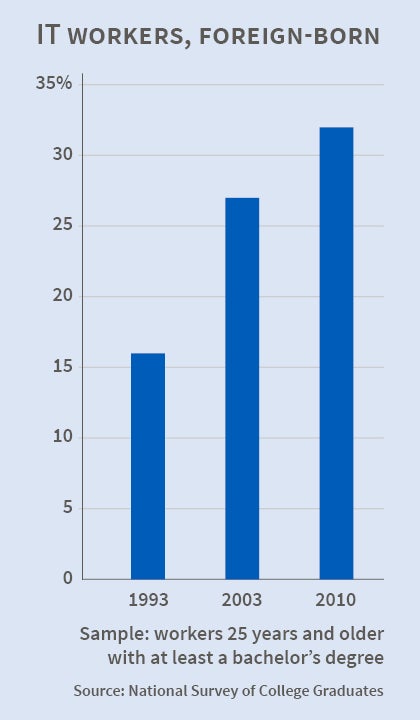

Between 1993 and 2010, the share of foreign-born workers holding information technology (IT) jobs in the United States doubled - from 15.5 percent to 31.5 percent of the IT workforce. U.S. higher education and immigration policies were key factors behind this rise, according to Finishing Degrees and Finding Jobs: U.S. Higher Education and the Flow of Foreign IT Workers (NBER Working Paper No. 20505).

Workers in India, China, and other countries where IT jobs don't pay as well as in the U.S. realize a substantial return if they get work in the U.S. Student visas allow workers to enter the U.S., obtain a degree, and then transition to a work visa. This can be an attractive alternative to obtaining scarce temporary work visas.

Authors John Bound, Murat Demirci, Gaurav Khanna, and Sarah Turner conclude that "demand among foreign students for U.S. higher education is high not because of the relative value of the degree itself, but because studying in the U.S. is a pathway to employment in the U.S., effectively lowering search costs, increasing networking opportunities, and providing a more easily interpretable skill set." They further note that "U.S. employers may prefer U.S.-trained workers because choosing workers from domestic institutions reduces their search and recruitment costs and the uncertainty in skill assessment."

While the number of H-1B work visas is capped, there is no restriction on issuance of student visas. An additional benefit of the student visa is the Optional Practical Training (OPT) program, which allows foreign students at U.S. universities to work and gain better access to the labor market.

The researchers find that 15.7 percent of all IT workers in the US were born abroad, entered the country on student visas, and then transitioned to work visas allowing them to stay. That share rises to 26.4 percent for workers under 35, who were likely to be affected by the tighter U.S. regulations on work visas instituted by the H-1B program in the last decade. Excluding those who came to the U.S. as youngsters on permanent visas, the share of foreign IT workers getting their highest degree from U.S. institutions is even higher. Furthermore, foreign students were more likely to be studying science and engineering than other fields. Their enrollment in computer science degrees closely followed U.S. labor market cycles.

The authors consider two explanations for why foreign students come to study in the U.S. - limited education options at home and improved employment chances in the U.S. They find important support for the latter explanation, at least in cases where wages are substantially higher in the U.S. and enrollment rates vary with U.S. labor market conditions. Thus, for foreign workers wanting to relocate to the U.S., increases in work-visa restrictions might boost their incentive to pursue higher education in the U.S., especially for science and engineering (S&E) degrees which can command high salaries.

"Given the high returns in the U.S. labor market for S&E degrees, students from India and China are willing to pay for education in the U.S. and increasingly have the means," the authors conclude. "In turn, U.S. educational institutions value foreign students at least in part for tuition revenues." This explains, at least in part, why U.S. colleges and universities are expanding their sub-doctoral degree programs.

The authors identify a number of factors that may influence the future flow of high-skill workers to the U.S. These include restrictions on student visas, the cost of higher education, whether U.S. universities can expand their graduate offerings, particularly science and engineering master's programs, the expansion of universities abroad, and the pay level for high-skilled jobs in the U.S.

-- Laurent Belsie