Do Virtual Schools Affect Brick-and-Mortar Counterparts?

The threat of 'disruption' from online education may induce traditional schools to improve quality.

Does competition from virtual schools make their brick-and-mortar counterparts better?

In The Competitive Effects of Online Education (NBER Working Paper 22749), David J. Deming, Michael Lovenheim, and Richard W. Patterson explore that question by analyzing the impact of online education on colleges with less-selective admissions policies.

What they learn both confirms and contradicts their hypotheses. They find that per-pupil spending increases, at public colleges at least, in response to competition from on-line education providers. They do not, however, find any evidence of tuition cuts from brick-and-mortar incumbents.

As of 2012, 6 percent of all U.S. bachelor's degrees were awarded for online study. The researchers investigate the impact of online entry on the behavior of traditional non-selective colleges. They focus on these schools because they are far more likely to draw students from a narrow geographic area than are their more selective counterparts. In 2013, nearly 40 percent of students at selective schools came from out of state, compared with 14 percent at less-selective four-year colleges and less than 6 percent at community colleges.

The researchers work with a sample of 8,782 schools. Roughly one third of them are public colleges or universities, and just over half are four-year institutions. They use a standard index of market concentration, the Herfindahl Index, to identify geographic regions where nonselective schools face comparatively less competition.

The key shift in the intensity of competition from on-line institutions, which underpins the study's analysis, comes from 2006 changes in federal law which dramatically increased the prevalence of online institutions. Until then, an educational institution could not award online degrees unless at least 50 percent of its students attended classes in person. As part of the 2006 changes, this rule was eliminated.

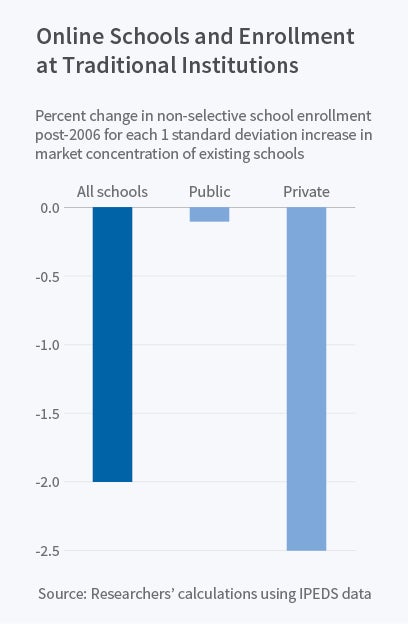

The researchers studied the years 2000 through 2013 and found that "less-competitive markets experienced relative declines in enrollment after the expansion of online degree programs." They found particularly convincing evidence of enrollment decline for less-selective private institutions, which they point out "are likely to be online schools' closest competitors."

The study found that four-year public colleges pumped up per-pupil instructional spending when they faced increasing online competition. However, this was not the case at two-year schools or private institutions. In the face of revenue shortfalls from declining enrollment, they appear to have reallocated spending to keep instructional levels steady.

Private nonselective schools partially made up for lower enrollment by increasing tuition. While that response might appear counterintuitive, the researchers note that student sensitivity to price changes is mitigated by the availability of government grants and loans. The study did not explore changes in tuition at public schools, on the ground that this "is not primarily determined by market competition."

In addition to studying the effects of the 2006 change in federal law, the researchers also use interstate differences in the degree of Internet penetration—which is a measure of the potential competitive role of online education—to assess the impact of such competition. They find that, after 2006, a 10 percent increase in penetration is associated with a 0.7 percent reduction in enrollment at non-selective schools and an increase of $1,587 per student in instructional expenditures. They caution that these results, while suggestive, lack the precision of their earlier analysis, which exploits differences in the degree of competition between brick-and-mortar educational institutions across Metropolitan Statistical Areas or counties.

The researchers conclude that "the threat of 'disruption' from online education may cause traditionally sluggish and unresponsive institutions to improve quality or risk losing students."

—Steve Maas