Philly's Sweetened Drink Tax Raised Prices, Altered Selection

After a new beverage tax was levied in January 2017, Philadelphia stores shifted their inventories away from sweetened beverages and toward alternative drinks.

In 2017, Philadelphia became the first large U.S. city to impose an excise tax on sweetened beverages. The goals were to promote consumers' health and to raise money. The cost of the tax was passed on fully to consumers, according to a new study comparing prices in Philadelphia stores with those in adjacent counties with no such tax.

In The Impact of the Philadelphia Beverage Tax on Prices and Product Availability (NBER Working Paper No. 24990), John Cawley, David Frisvold, Anna Hill, and David Jones also report that the tax spurred the city's stores to expand their inventory of unsweetened drinks.

Philadelphia instituted an excise tax of 1.5 cents per ounce of sweetened beverages on January 1, 2017. Unlike other municipalities, it imposed the tax on both diet and regular beverages. The tax was applied at the distribution level, rather than charged at the cash register.

The researchers collected data on the price and availability of a wide range of beverages in retail stores in Philadelphia and surrounding areas in November and December 2016, returning in the same months the following year to obtain comparable statistics.

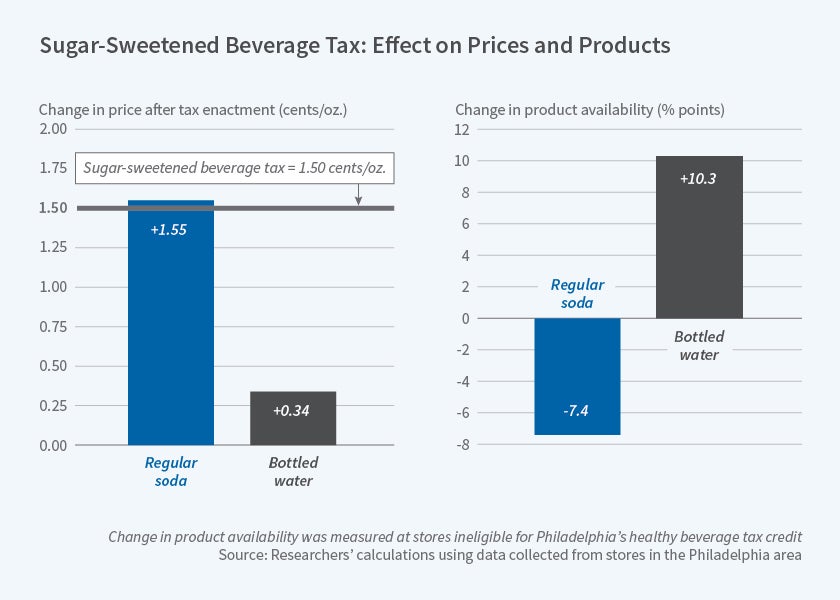

Of the sampled beverages, prices on average rose 1.56 cents per ounce more in Philadelphia, where they were subject to the new tax, than they did in the surrounding communities. The differential was even greater for energy drinks and juice drinks (up by nearly 2 cents an ounce), compared with regular soda (1.55 cents per ounce) and diet soda (1.59 cents per ounce).

Price hikes were larger on individual servings than on large containers and multipacks, which may reflect the tendency of consumers to be less price-sensitive on single-serving drinks than on shopping trips on which they purchase large quantities.

The pass-through of the tax was higher at independent retailers than at chain stores. The researchers cite two possible explanations: Locally owned stores have greater flexibility in setting prices, and the chains may have spread the tax burden among their affiliates to avoid price competition among branches within and outside Philadelphia.

Consumers living in high-poverty areas — where they were more likely to be dependent on small neighborhood stores — faced higher price hikes than did those living in more affluent areas. A 10 percentage point increase in the poverty rate of a given area was associated with a 0.2 cents per ounce increase in the pass-through of the tax on soda.

Stores closer to the suburbs, and those facing competition from areas without the tax, passed through a smaller share of the tax hike. For each additional five minutes of travel time a store was located from an untaxed competitor, the pass-through increased by 0.37 cents per ounce on all taxed beverages.

In the wake of the beverage tax, Philadelphia stores shifted their inventories away from sweetened beverages. For example, compared with their counterparts outside the city, Philadelphia stores were more than 10 percentage points more likely to carry bottled water after the tax was imposed.

— Steve Maas