How Consumers Respond to Calorie Information on Their Menus

Providing consumers with calorie information improves the accuracy of post-meal estimates of calorie counts by about 4 percent, or 65 calories.

Listing calorie counts on restaurant menus reduces the likelihood that diners will underestimate the number of calories in their orders, according to John Cawley, Alex M. Susskind, and Barton Willage. Their study, Does Information Disclosure Improve Consumer Knowledge? Evidence from a Randomized Experiment of Restaurant Menu Calorie Labels (NBER Working Paper 27126), explores the impact of a 2018 national requirement that chain restaurants with 20 or more locations provide consumers with calorie information.

The requirement was introduced in hopes that improved consumer awareness of calorie intake might help to slow the rising US obesity rate. More than half of the average American’s food budget is spent on away-from-home meals.

The researchers conducted a randomized controlled trial in a sit-down restaurant on a college campus. The study included 1,546 participants. Parties of restaurant patrons were randomized to either a control group, which received menus without calorie information, or a treatment group, which received menus with calorie counts. At the end of the meal, a researcher asked the study participants to provide demographic information as well as their estimate of the number of calories in their meal. This estimate was then compared with the actual number of calories in the meal that the participant had ordered, based on their receipt. The calorie counts were sourced from MenuCalc, software based on the US Department of Agriculture nutritional database.

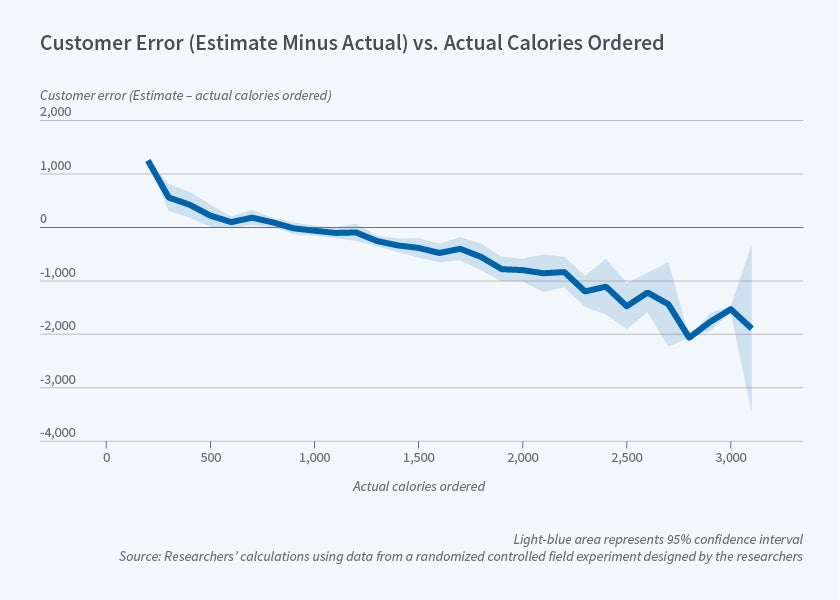

Diners who did not receive information on calorie counts were often far from the mark in their estimates. Sixty percent underestimated the number of calories they ordered by at least 10 percent, 45 percent underestimated by at least 25 percent, and 14 percent underestimated the number of calories by 50 percent or more. As the number of calories actually ordered rose, the extent of underestimation also rose.

Diners in the treatment group, who received calorie information on their menus, were 4 percent more accurate in estimating the number of calories in their meals than the control group, who received no such information. This is a difference of about 65 calories. The diners in the treatment group were also 29 percent less likely to underestimate the number of calories ordered by more than 50 percent.

While providing calorie information improved consumer knowledge, the typical diner who received this information still had trouble accurately estimating caloric intake. Even among the treatment group, the average absolute value of error was 34 percent or 436 calories — the equivalent of about one and a half cheeseburgers.

The researchers note that their participants were relatively well-educated, which could limit the generalizability of the findings. Forty-five percent of the participants had a graduate degree, another 26 percent were college graduates, and 18 percent were college students. The researchers did not find evidence that the effect of calorie labels varied by level of education.

— Jennifer Roche