Long-Term Effects of Affirmative Action Bans

Affirmative action policies, which give preference in college admissions to students from underrepresented minority (URM) groups, have been a subject of debate and legal scrutiny in the US. The recent Supreme Court ruling in Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. President and Fellows of Harvard College barred explicit racial and ethnic preferences in college admissions as unconstitutional. Prior to this ruling, nine states had banned affirmative action in public university admissions.

In The Long-Run Impacts of Banning Affirmative Action in US Higher Education (NBER Working Paper 32778), Francisca M. Antman, Brian Duncan, and Michael F. Lovenheim examine the effects of state-level affirmative action bans on the educational attainment and labor market outcomes of students from underrepresented groups. They focus on the first four states to implement such bans: Texas (1997), California (1998), Washington (1999), and Florida (2001).

State-level bans on affirmative action in higher education reduced educational attainment for Blacks and Hispanics and had varied, but mostly negative, labor market consequences for these groups.

Using American Community Survey data (2001–21), the researchers analyze a sample of non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, and non-Hispanic White adults aged 25–51, born between 1970 and 1994. They compare cohorts who were older than 17 at the time of the ban and likely unaffected by it to those younger than 17, who were subject to the new admissions policies.

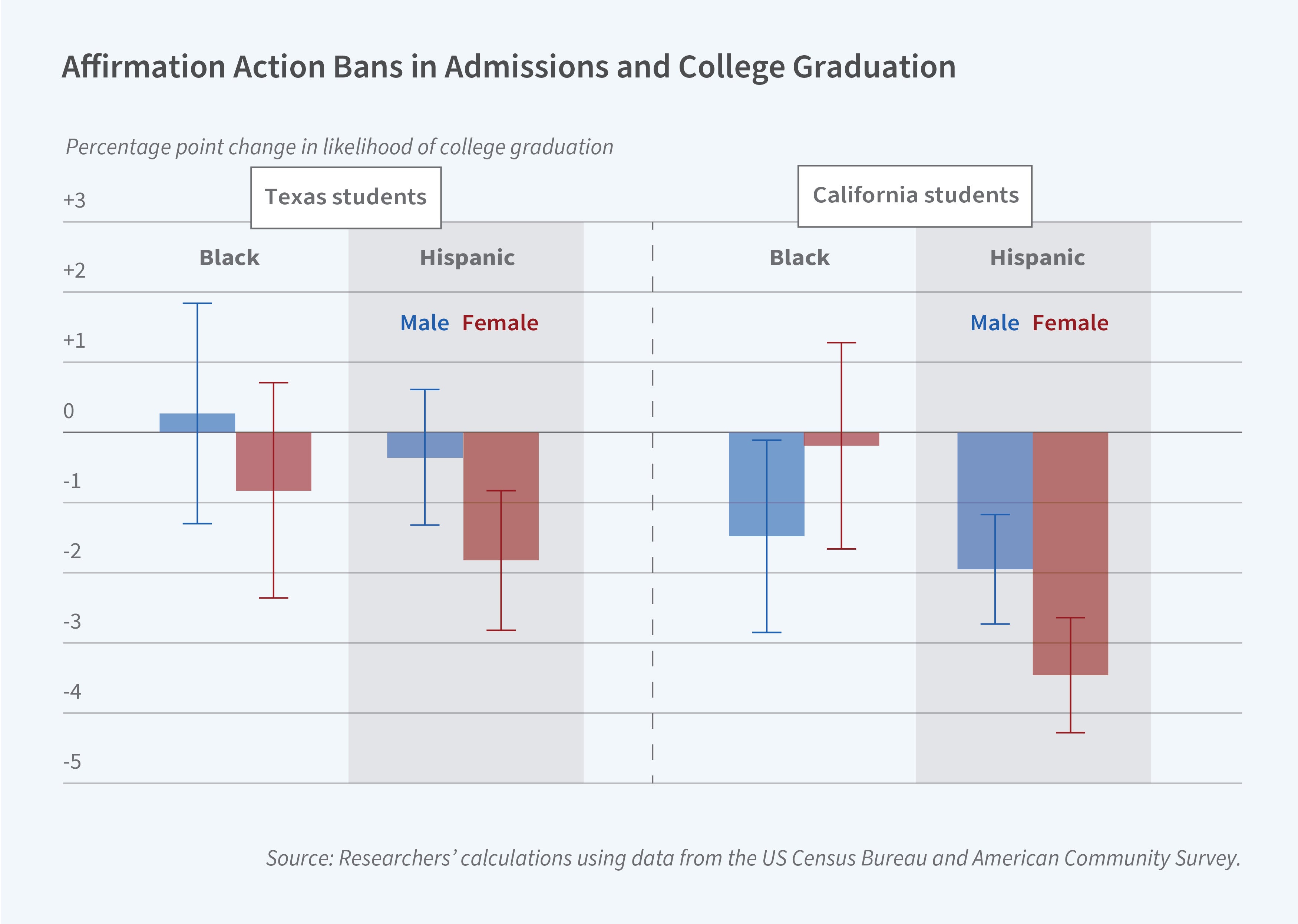

Pooling the data from all four states, they find that Black and Hispanic men were 1.1 and 1.6 percentage points less likely to complete college relative to White men, respectively, after the ban. For women, these figures were 0.7 and 1.7 percentage points. Graduate degree attainment showed similar patterns, with Black and Hispanic men 0.5 and 0.8 percentage points less likely to obtain a graduate degree than White men and women 0.3 and 1.3 percentage points less likely.

Labor market outcomes displayed more varied outcomes. While Black men earned about 1.3 percent more relative to White men, and Hispanic men earned 0.9 percent less after the bans, Black and Hispanic women earned 8.1 percent and 7 percent less than White women, respectively. Employment rates for Black and Hispanic men were 2.1 and 1.8 percentage points higher, while Black women saw a 1 percentage point decrease and Hispanic women a 0.3 percentage point increase.

When comparing individuals in states with and without bans across racial and ethnic groups, the researchers find little impact of bans on college attainment for men but a 4 percentage point decline in college completion and a 1.7 percentage point decline in graduate degree attainment for Hispanic women. Earnings in states with bans were 2.6 percent higher for Black men, 3.3 percent higher for White women, 4.2 percent lower for Black women, and 8.1 percent lower for Hispanic women. The employment rate was 3.6 percentage points lower for Hispanic women, who appear to be particularly adversely affected by bans.

The researchers note that positive labor market effects for Black men and negative effects for Black and Hispanic women could be due to differences in the college major choices of URM men and women, or to “mismatch effects” if students admitted under affirmative action struggle academically on account of a gap between their preparation for college and that of their peers. More generally, the researchers caution that the heterogeneity found across states and groups suggests that some contextual factors are at work in determining the impact of college attendance.

— Leonardo Vasquez

Francisca Antman acknowledges partial research support from the National Science Foundation, under NSF Award Number SES: 2121120.