US-China, STEM Researchers, and Students

Since 2015, geopolitical tensions between the US and China have risen. There has been an increase in anti-China rhetoric from US politicians and growing anti-China sentiment in the population. These developments have been manifested in trade barriers and FBI-DOJ investigations of Chinese American scientists under suspicion of espionage and intellectual property theft.

In Building a Wall around Science: The Effect of US-China Tensions on International Scientific Research (NBER Working Paper 32622), Robert Flynn, Britta Glennon, Raviv Murciano-Goroff, and Jiusi Xiao investigate the effects of China-US geopolitical tensions on science. The scientific communities in the two countries have historically been well connected. The authors’ data on US graduates who took a job shows that between 2008 and 2019, ethnically Chinese students accounted for about 18 percent of STEM graduates in the US, and scientists in the two countries frequently collaborated and cited each other’s work.

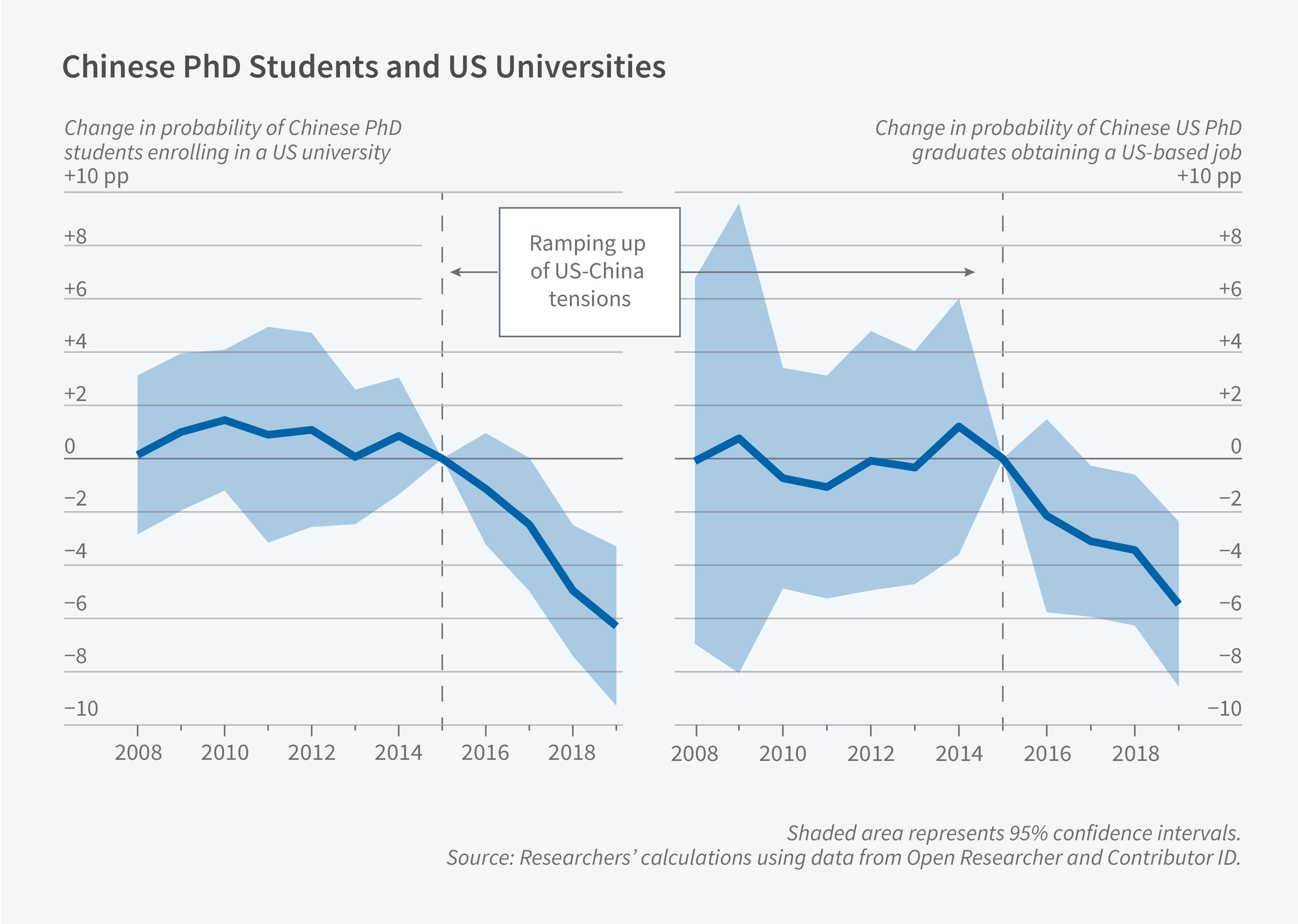

Rising geopolitical tensions have been associated with a decline of almost 4 percent in the probability of Chinese students enrolling in a US PhD program.

The researchers study the effects of rising geopolitical tensions on graduate study and the employment of Chinese scientists in the US, US-China citation flows, and the productivity of US and Chinese scientists. They analyze curricula vitae that scientists post publicly on their Open Researcher and Contributor ID profiles, and they track citation and publication patterns using Dimensions, a bibliometric database.

A comparison of ethnically Chinese students and non-Chinese students before and after 2015 reveals a decline of about 3.7 percentage points in the probability of Chinese students enrolling in a US PhD program, and an increase of 2.1 percentage points in their probability of attending a PhD program in a non-US Anglophone country such as the UK, Canada, or Australia, countries that are not directly implicated in rising tensions. Among PhD students graduating from US PhD programs, the likelihood that a Chinese graduate’s first job was in the US decreased by 3.6 percentage points, while the likelihood that it was in a non-US Anglophone country increased by 0.9 percentage points.

The researchers also analyze citation flows between China and the US, using citations to researchers based in the UK as a control. They find that Chinese citations of US publications declined by 6.5 percent after 2015; citations to recent US publications declined by even more, 10 percent. This decline applied even to high-quality “frontier” US research. By contrast, the researchers find no statistically significant evidence of a decrease in US citations of Chinese publications.

The decline in Chinese citations of US work does not appear to coincide with a decline in productivity for Chinese scientists. Comparing before- and after-2015 publications of Chinese scientists based in China whose citation patterns heavily relied on US work, and again using the UK as a control, does not suggest any change in productivity for China-based scientists. In contrast, the productivity of Chinese scientists in the US, as measured by impact-weighted publications in US-based journals, fell by about 3 percent after 2015.

—Shakked Noy