Returns to Port Infrastructure Investments

Ships carry nearly 80 percent of internationally traded goods, which makes port infrastructure essential to a well-functioning trading system. In Investment in Infrastructure and Trade: The Case of Ports (NBER Working Paper 32503), Giulia Brancaccio, Myrto Kalouptsidi, and Theodore Papageorgiou examine the returns to investments in port infrastructure.

The researchers analyze data on the universe of port calls between 2016 and 2021 by bulk carriers with a deadweight of more than 10,000 tons. They find that the average port call lasts 117 hours, one-third of which is waiting time and the rest service time. There is substantial variation across ports and years, with wait times more variable than service times.

Increasing port capacity can significantly reduce congestion, increase trade, and create positive spillover effects for nearby ports. However, investment returns crucially depend on port geography and macroeconomic volatility.

When a port is not full, ships can be serviced immediately upon arrival. Otherwise, the ship must join a queue. When demand for service surpasses port capacity, further increases in demand can overwhelm the port and result in a lengthening of the queue. Investments in capacity generate savings in time-in-port, but only when the port would otherwise be full.

Congestion at one port can influence nearby ports, as carriers may reroute ships based on factors like distance, time at port, and costs. The researchers estimate that carriers are willing to pay 90 cents per deadweight ton of their vessel — or $18,000 for a 20,000-ton ship — to reduce time at port by one day. This translates to $45,000 for the average ship. Demand is highly responsive to time at port: 83 percent of shippers do not choose the closest port to their shipments’ ultimate destinations.

Investments in capacity at a given port reduce demand for services at other ports, as carriers take advantage of the newly expanded capacity. However, in addition to this substitution effect, this creates positive spillovers across ports: Other ports also become less congested and this, in turn, makes them more attractive to carriers who become more likely to choose them. On average, when a port expands its capacity by one ship, it sees 42 percent more trade and 4 percent less congestion. All other ports see 0.2 percent less trade and 0.6 percent less congestion.

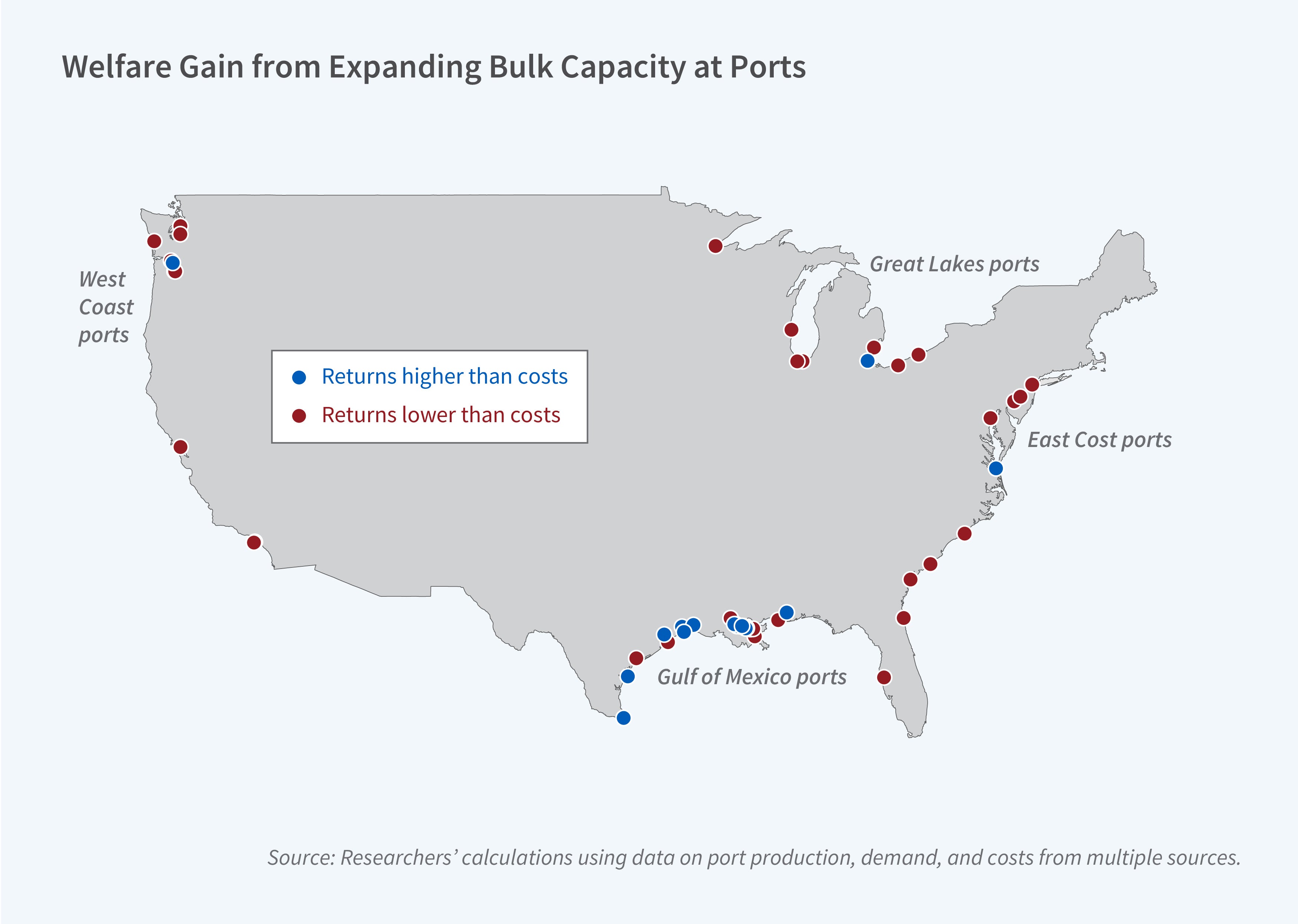

The increases in trade and welfare are largest when infrastructure investments are targeted at ports that are already congested and in convenient locations, but also those ports whose closest substitutes are themselves congested and geographically attractive. After accounting for both the land and construction costs of expanding port infrastructure, the researchers estimate that increasing port capacity by one ship would yield benefits in excess of costs at 15 out of 51 US ports. The returns are highest for ports on the Gulf Coast.

Finally, in line with concerns about disruptive shocks becoming more common, the researchers compute how frequent macroeconomic shocks need to be to warrant investment. An increase in volatility makes both very high and very low demand realizations more likely. While low demand realizations matter little, high demand shocks can lead to sharp increases in congestion. As a result, higher volatility makes infrastructure investment more valuable: on average, welfare gains double when volatility doubles, and net returns turn positive for 10 additional ports. At one extreme, welfare gains quadruple for some ports. However, at the other extreme, for a sizable share of ports (25 percent) net returns do not turn positive even when volatility more than triples; for these ports, investment is unlikely to be warranted even if the policymaker only cares about resilience.

—Whitney Zhang

The researchers gratefully acknowledge financial assistance from the NBER Transportation Economics in the 21st Century Project grant, as well as the National Science Foundation Award SES-231533-231534-231535.