Nudges and Retirement Saving

Automatic enrollment and automatic contribution escalation in retirement savings plans have become increasingly prevalent in the United States. 40 percent of US private industry workers participate in savings plans with automatic enrollment, and 40 percent of plans administered by Vanguard automatically escalate employee contribution rates unless employees opt out. The SECURE 2.0 Act of 2022 mandates that most 401(k) plans established after 2022 must automatically enroll new employees and, by default, automatically escalate. Additionally, ten US states require employers without 401(k) plans to automatically to enroll employees in Individual Retirement Accounts.

In Smaller than We Thought? The Effect of Automatic Savings Policies (NBER Working Paper 32828 and formerly RDRC Paper NB23-20), researchers James J. Choi, David Laibson, Jordan Cammarota, Richard Lombardo, and John Beshears examine the long-term effectiveness of automatic savings policies at increasing retirement asset accumulation. The study analyzes data fro,m nine firms that introduced automatic policies between 2003 and 2011, comparing 62,430 employees hired in the year after policy implementation to 55,937 employees hired in the year before. They track employees for 60 months after hire. Some of the firms in the sample introduced automatic enrollment without automatic escalation of contribution rates. Others added a default of automatic escalation to plans that already had automatic enrollment. A third group enacted both automatic enrollment and default automatic escalation simultaneously.

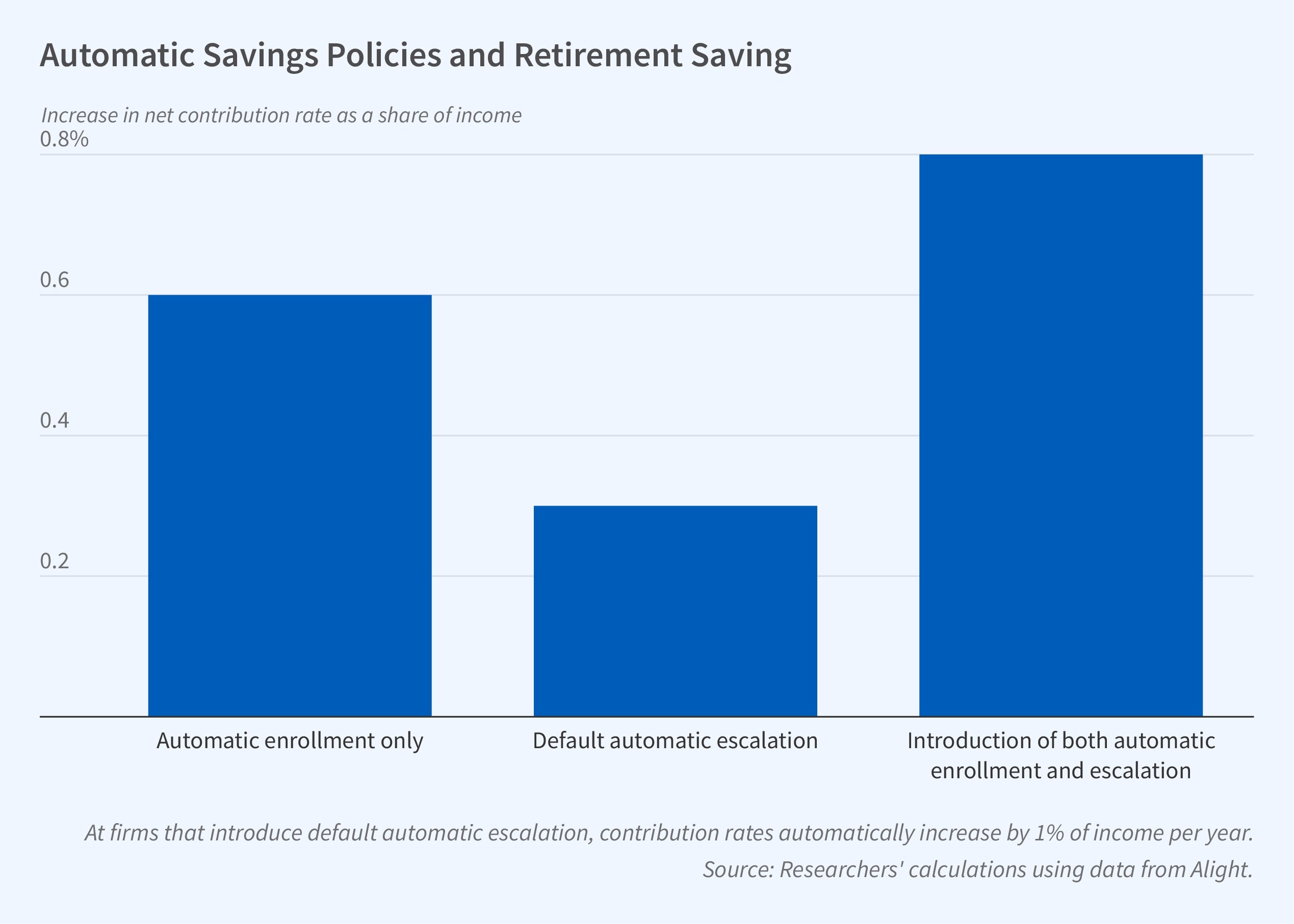

Automatic savings policies raise retirement savings rates over a five-year horizon by less than 1 percent of income.

Automatic enrollment alone increased the retirement contribution rate net of withdrawals by an average of 0.6 percent of income. Adding automatic escalation to existing automatic enrollment increased the net contribution rate by 0.3 percent of income, while implementing both automatic enrollment and automatic escalation simultaneously increased the net contribution rate by 0.8 percent of income. These effects are smaller than those reported in previous studies that focused on shorter periods and did not account for factors like withdrawals from retirement accounts before retirement age and incomplete employer match vesting.

The modest impact of automatic policies has four main sources: Many individuals not subject to automatic policies eventually choose positive contribution rates, narrowing the gap between automatic and nonautomatic policies over time. Acceptance of default automatic escalation is surprisingly low, with only 40 percent of employees accepting the first automatic increase. High employee turnover rates prevent full vesting of employer contributions. And employees frequently cash-out 401(k) balances upon job separation. The researchers estimate that 42 percent of balances are cashed out upon departure.

Automatic policies lead to more people leaving jobs with small positive 401(k) balances which are subsequently more likely to be cashed out than larger balances. Individuals affected by to automatic enrollment policies have an average leakage rate (conditional on having a positive balance) that is 8 percent of balances higher than those not subjected to the policies.

– Leonardo Vasquez

The research reported herein was performed pursuant to grant RDR18000003 from the US Social Security Administration (SSA) funded as part of the Retirement and Disability Research Consortium. The opinions and conclusions expressed are solely those of the author(s) and do not represent the opinions or policy of SSA, any agency of the Federal Government, or NBER. Neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of the contents of this report. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not necessarily constitute or imply endorsement, recommendation or favoring by the United States Government or any agency thereof.