South Korea’s Industrial Policy: Growth with Inefficiency

The Heavy and Chemical Industry Drive of 1972 to 1979 increased the size and output of targeted firms and industries but was also associated with increased misallocation of resources.

Between 1965 and 1990, four “tigers” — South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore, and Hong Kong — were among the leaders in a period of rapid industrialization and economic growth that became known as the East Asian Miracle. Some analysts have linked this growth to these countries’ reliance on government cultivation and support of strategic industries. However, the overall efficacy of this form of industrial policy remains debatable.

Two recent papers — one using firm-level balance sheets, the other using plant-level production data — examine the long-term effects of a high-profile example of industrial policy: South Korea’s Heavy and Chemical Industry (HCI) Drive of 1972 to 1979, which targeted development in steel, nonferrous metal, electronics, machinery, chemicals, and shipbuilding. This push was concentrated in nine southeastern regions of the country, where the Korean government built large HCI complexes. Both studies estimate the impacts of the HCI Drive by comparing firms’ long-term growth in targeted industry-region pairs with that in non-targeted industries or regions.

In The Long-Term Effects of Industrial Policy (NBER Working Paper 29263), Jaedo Choi and Andrei Levchenko find that firms with access to subsidized credit through the HCI Drive were larger than unsubsidized firms even 30 years after subsidies ended. As part of its HCI push, the Korean government backed large foreign loans for targeted firms, allowing them to borrow at interest rates far below those available domestically. The researchers find that a subsidized firm that received the average credit subsidy during this period experienced 8.6 percent higher annual sales growth between 1982 and 2009 than a comparable nonrecipient firm.

In The Plant-Level View of an Industrial Policy: The Korean Heavy Industry Drive of 1973 (NBER Working Paper 29252), Minho Kim, Munseob Lee, and Yongseok Shin find similar evidence that targeted industry-regions saw higher growth during and after the HCI Drive. These effects persisted until at least 1987, when the researchers’ data end. They document growth in targeted industry-regions as a whole, as well as in the average number of employees per plant in these sectors. In particular, they find an increase in the number of very large plants.

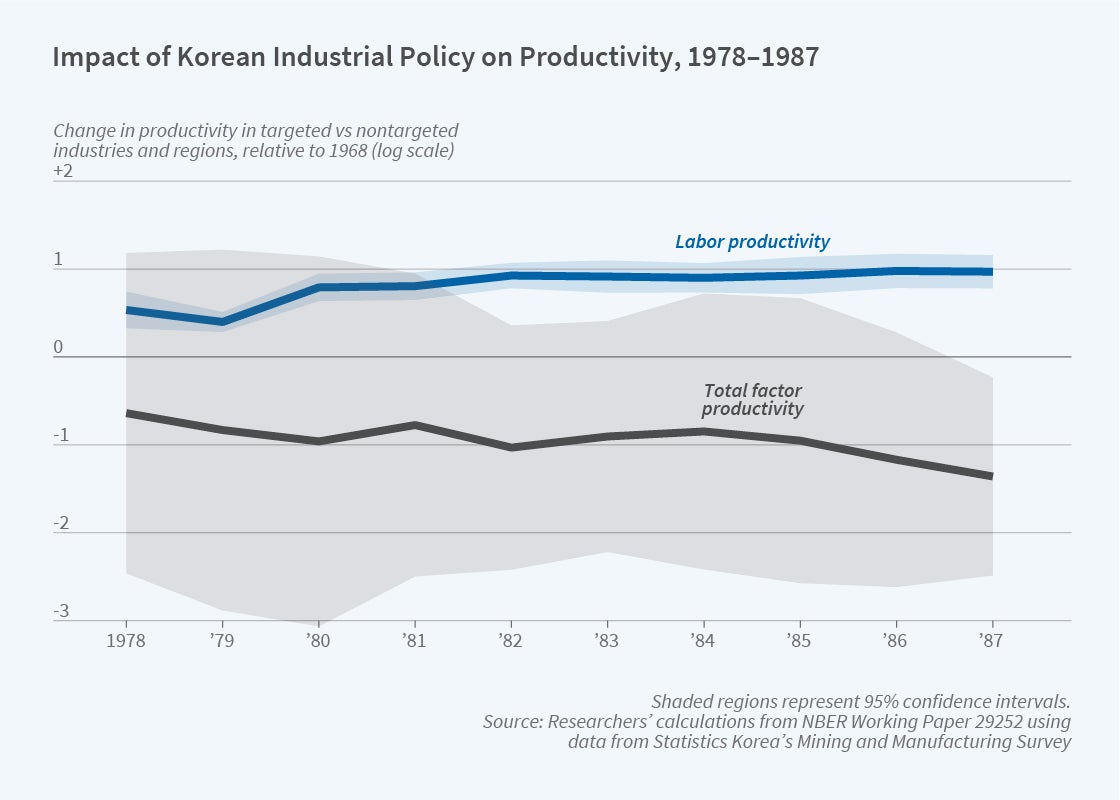

An increase in the size and output of industries targeted by the HCI Drive does not imply that these industries became more productive. Indeed, while this push increased both aggregate labor productivity and plant-level total factor productivity (TFP), it did not increase aggregate TFP at the industry-region level. This is because resource misallocation increased substantially in targeted industry-regions, as resources were directed to lower-productivity uses. The researchers suggest that this may be explained by chaebols — megaconglomerate firms, mostly family owned — that preferentially attracted support in the HCI Drive. If this misallocation had been avoided, average TFP in the targeted industry-regions would, on average, have been 40 percent higher in 1980.

The factory-level analysis of the HCI Drive suggests two additional conclusions. First, higher flows of intermediate goods from targeted industries to non-targeted industries may have yielded broad benefits by lowering the cost of inputs for the latter group. Second, to the extent that production processes exhibit learning by doing and an initial burst of output reduces future production costs, the policy of supporting some industries could have raised welfare in South Korea by increasing labor productivity not just during, but after the period when subsidies were available. The firm-level study suggests welfare gains of between 22 and 31 percent through this channel.

— Lucy E. Page