Effects of the First Court Ruling against School Segregation

Hispanic students in California who began schooling after Mendez v. Westminster remained in school 0.9 years longer and were 19.4 percent more likely to graduate from high school.

The Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education ruling in 1954 is widely viewed as the seminal decision outlawing racial segregation of schools. But a decade earlier, in Mendez v. Westminster, a federal district court ruled against segregation of Mexican Americans in California schools. This case was the first successful challenge to segregation based on the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment to the US Constitution. Filed against school districts in Orange County, the case never reached the national level because the defendants decided not to pursue it after losing at the appellate level in 1947.

In The Long-Run Impacts of Mexican-American School Desegregation (NBER Working Paper 29200), Francisca M. Antman and Kalena Cortes document how Mendez boosted the educational attainment of Hispanics in California.

Determining the impact of segregation in California is complicated, because unlike in southern states that mandated separate schools for Blacks and Whites, in California segregation primarily occurred at the local level. Segregation was subtler: school boundaries were drawn to create Mexican zones, and any White children who happened to live in those areas were offered the opportunity to transfer out.

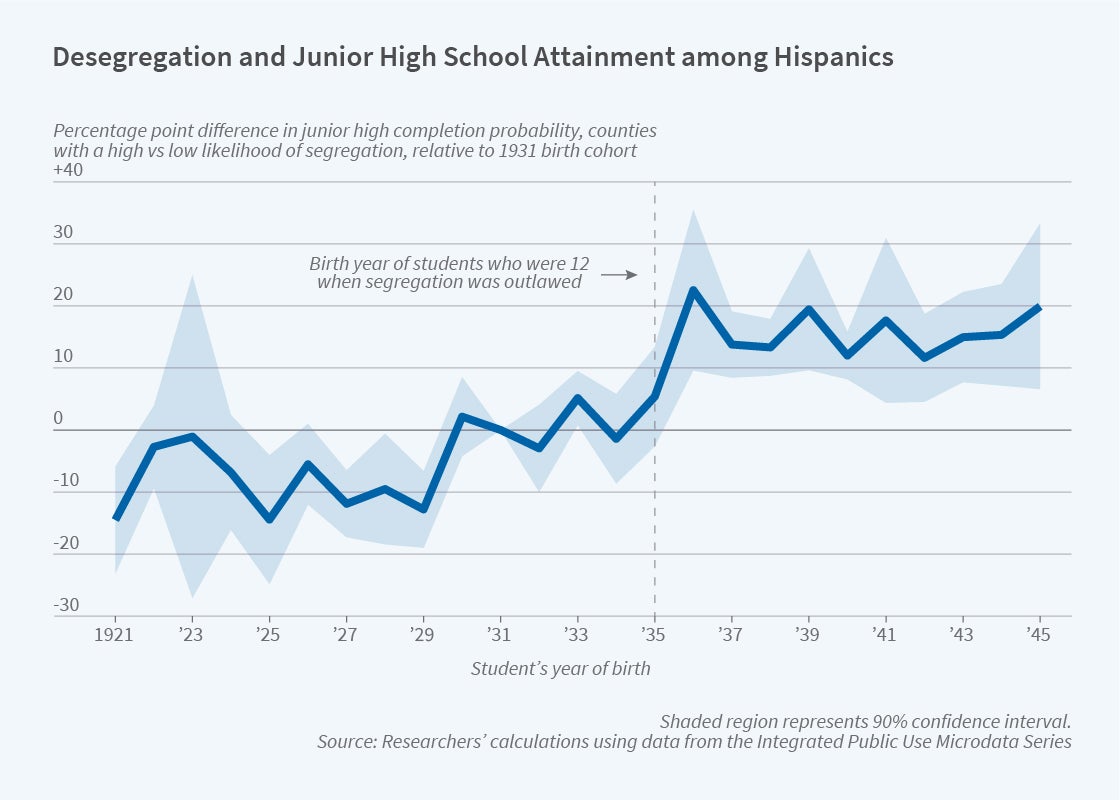

In the absence of official records designating which California districts practiced segregation, the researchers rely on historical accounts indicating that segregation was most prevalent in counties with a large share of Hispanic students. They assume that schools were segregated in counties that fell in the top quarter statewide in their concentration of Hispanics.

In those counties, Hispanic students who began schooling after Mendez took effect remained in school 0.9 years longer than students who began schooling a decade earlier. The post-Mendez cohort was 18.4 percent more likely to graduate from junior high school and 19.4 percent more likely to graduate from high school than the pre-Mendez cohort.

At the same time as Hispanics marked gains in educational attainment, their non-Hispanic White classmates showed a slight decline. The drop in attainment for non-Hispanic Whites was much smaller than the increase for Hispanics; the researchers conjecture that it might have resulted from a reallocation of resources.

Prior to the Mendez decision, Hispanic students in low-segregation counties — those in the 25 percent of counties with the lowest ratio of Hispanics to non-Hispanics — completed an average of 12 years of schooling, compared with nine years for their Hispanic peers in high-segregation counties. Mendez had no appreciable impact on the outcomes for Hispanics in low-segregation areas.

— Steve Maas