Cross-Country Evidence on Labor Market Fluidity and Wage Growth

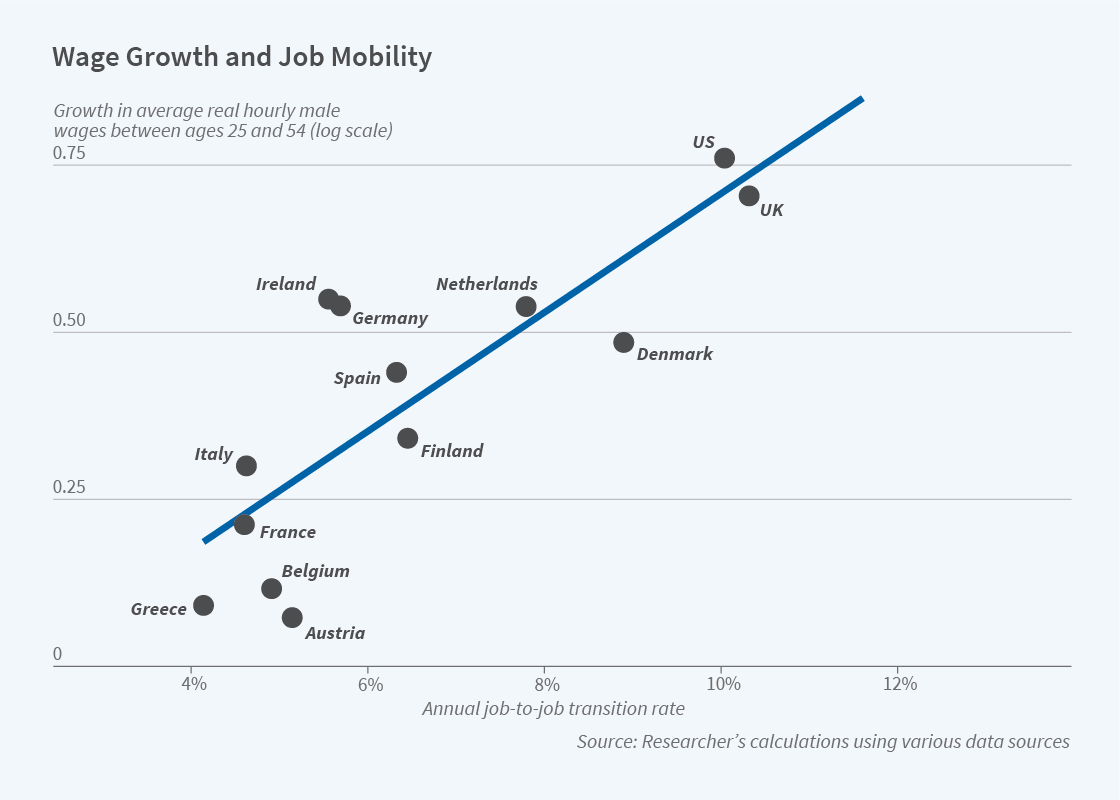

Across OECD nations, more fluid job markets are associated with greater accumulation of worker skills and faster wage growth.

Job-to-job labor market flows vary substantially across countries. In Labor Market Fluidity and Human Capital Accumulation (NBER Working Paper 29698), Niklas Engbom finds that greater labor market fluidity — more frequent job changes per worker — is associated with greater human capital accumulation as workers acquire new skills. Greater fluidity also allows workers to find jobs where their skills are most useful. As a result of these two factors, workers’ wages increase faster in nations with more fluid labor markets.

Engbom analyzes worker-level panel data for 23 OECD countries over a period of more than 20 years. He finds substantial variation in labor market fluidity across nations. The most fluid job markets are 2.5 times as fluid as the least, and they also exhibit more rapid wage growth over the life cycle. This is not due to differences across nations in age, education, or workforce composition. It is only partially driven by the average number of job changes over the course of a career. On average, worker job changes are associated with annual wage increases of between 5 and 6 percent in both high and low fluidity labor markets. Wage jumps associated with job changes account for about a quarter of the higher life cycle wage growth that is observed in high relative to low fluidity job markets. Most of the additional wage growth in high fluidity countries occurs while workers are employed at continuing jobs, not when they move from one job to another.

The researcher interprets these empirical results by developing a theory of lifetime skill accumulation in a frictional labor market. The framework incorporates both endogenous accumulation of human capital on the job and elements of a job ladder with workers moving from job to job in search of the ideal fit for their skills. He benchmarks the life cycle model using data from the United States, a high fluidity nation where wage growth and mobility both decline as workers age. He also compares companies’ hiring costs in different nations. He finds that differences in labor market fluidity account for half of the faster wage growth experienced by high fluidity economies. About one-third of the disparity across countries is due to workers climbing job ladders more slowly in less fluid labor markets, and another third is due to slower accumulation of skills.

The cross-country data also reveal disparities in on-the-job training investment. Workers spend more time on training in high fluidity nations, as well as in high fluidity occupations and sectors within nations. They train more in high paying, more productive companies, which offer them a higher return — higher wages — on their skills. Workers also train less at smaller, lower paying firms in less fluid sectors because they have a harder time moving to jobs that better utilize their skills. Expecting lower returns, they invest less in training.

Lower labor market fluidity correlates with policies and regulations that raise firms’ costs of doing business as well as the costs of starting a business. Engbom points to the case of Spain to illustrate the possible effects of regulatory change. In the mid-1990s, Spain shifted from having the most stringent employment protection in continental Europe to having some of the least protective institutions. After a lag, labor market fluidity rose substantially. Wages of new entrants to the labor force initially fell, but they grew faster as workers aged. By age 50, average wages after the increase in fluidity were substantially higher than wages at the same age before labor market reforms.

— Laurent Belsie