Parental Reactions to Disabled Children’s Prospective Loss of Benefits

In 2022, the US Supplemental Security Income (SSI) program provided $51 billion in cash payments to 1 million children and 5.5 million adults with disabilities and low incomes. Eligibility standards for potential beneficiaries under 18 years of age require “marked and severe functional limitations” in activities like school performance and social interaction. Most eligible children qualify for the maximum annual benefit of $10,000. Adults are eligible for SSI only if they are unable to do gainful work.

When they reach 18, childhood SSI recipients are reevaluated for benefit eligibility under the adult standard. Nearly 40 percent lose benefits. The disqualification rate is nearly 70 percent for children who were eligible due to mental and behavioral conditions, more than half of which involved an ADHD diagnosis or speech or language delays.

In The (Lack of) Anticipatory Effects of the Social Safety Net on Human Capital Investment (NBER RDRC Center Paper NB19-21) Manasi Deshpande and Rebecca Dizon-Ross conducted a randomized controlled trial to study whether parents changed their investments in their child’s human capital when they received information about the likelihood of SSI benefit loss when their child turned 18.

Reducing parents’ expectations about the likelihood that their child will lose Supplemental Security Income benefits at age 18 did not increase parents’ human capital investments in their child.

At the start of the experiment, about 60 percent of parents in a final sample of 5,968 beneficiaries were unaware of the adult eligibility review. They believed their children would not be removed from SSI. Seventy-three percent of the beneficiaries came from single-parent households, 83 percent had a mental disability, 13 percent had a physical disability, and 4 percent had an intellectual disability. Around 30 percent were female.

The final sample of beneficiary households was about 17 percent of an initial sample that was invited to complete the survey. They were drawn from Social Security Administration records from October 2021 to January 2022. Households in the initial sample had at least one child enrolled in SSI who was 14–17 years old and had a substantial predicted likelihood of being denied SSI as an adult.

The researchers divided the sample into two main groups. Each group watched a video. The first part of each video had an introduction and brief overview of the SSI program. The last part of each video was an overview of the experiment’s Resource Center offerings. The middle segment differed between the randomly selected treatment and control groups. Control group parents watched “placebo” (innocuous) instructional videos on either the history of the SSI program or the geographic distribution of SSI recipients. Treatment group parents received information about their child’s predicted likelihood of removal from the SSI program at age 18. They were told that if their child were removed from SSI they would no longer receive monthly payments from SSI.

The information offered in the treatment video raised parents’ estimates of the probability of SSI removal by 18 percentage points relative to control group parents. Having shown that information on the probability of removal shifted parental beliefs, the researchers sought to analyze how heightened expectations about losing SSI affected parental investments in their children’s human capital.

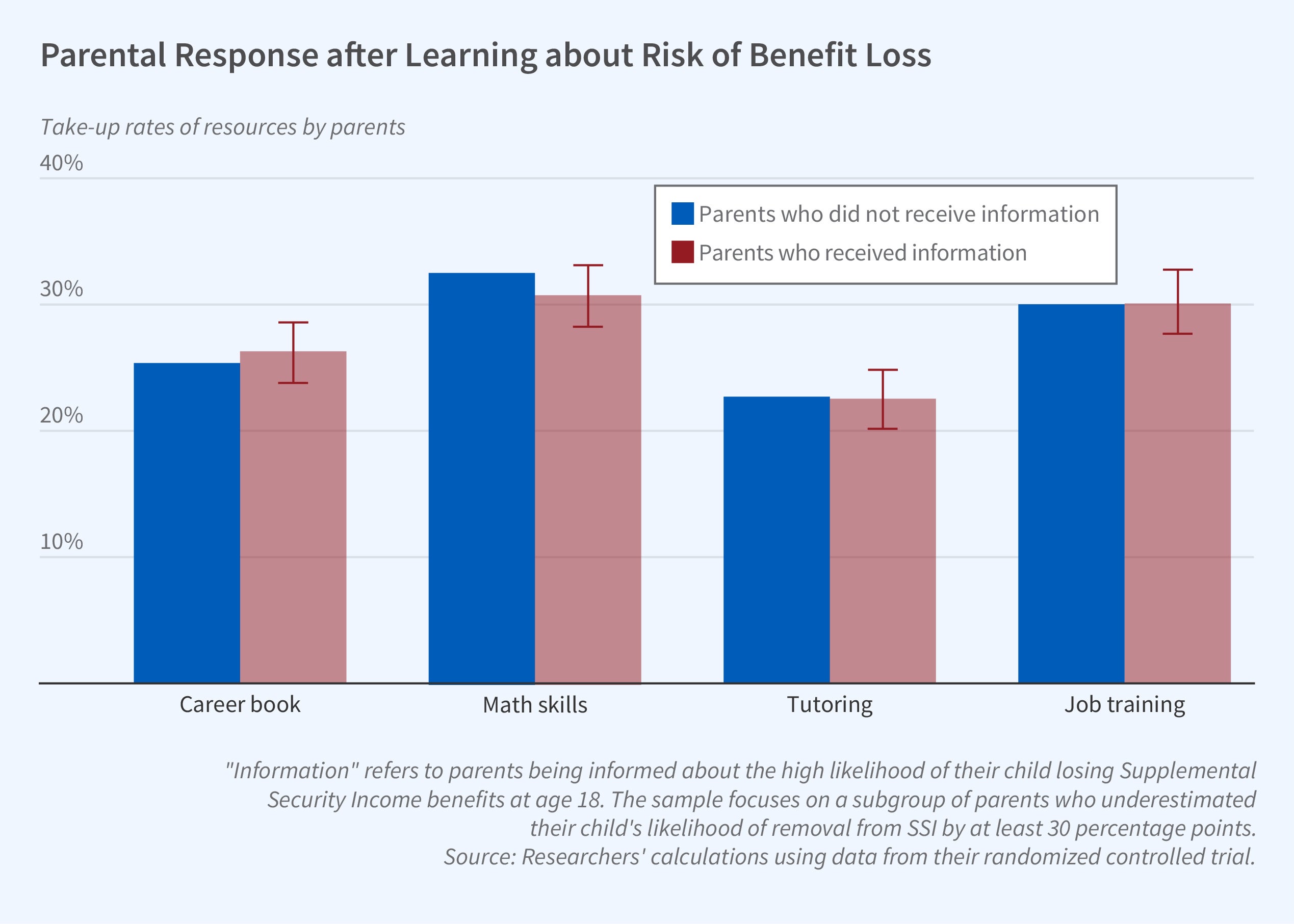

The researchers measured parental investment in their child by whether parents took advantage of one of four “human capital resources” offered in the Resource Center described in the video: help signing up for free job-training services provided by their state, an online educational program with grade-appropriate math and computer skills lessons, a choice of a $50 cash prize or $300 worth of one-on-one tutoring for their child (conditional on winning a lottery), and either a $40 cash payment for completing the survey or $35 in cash plus a career book for teens valued at $16.

Better information about SSI removal had no statistically significant effect on take-up of the human capital resources. Approximately 30 percent of both the control and treatment groups took advantage of the Resource Center offerings. Some explanations for the lack of human capital investment response include parents working more themselves to make up the lost money, the effect of nonfinancial goals on investment decisions, and the negative wealth shock (from the expected loss of benefits) reducing human capital investment.

— Linda Gorman

The research reported herein was performed pursuant to grant RDR18000003 from the US Social Security Administration (SSA) funded as part of the Retirement and Disability Research Consortium. The opinions and conclusions expressed are solely those of the author(s) and do not represent the opinions or policy of SSA, any agency of the Federal Government, or NBER. Neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of the contents of this report. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not necessarily constitute or imply endorsement, recommendation or favoring by the United States Government or any agency thereof.