Tariffs and US Labor Productivity: Evidence from the Gilded Age

US tariff policy reduced labor productivity in the American manufacturing sector during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, as Alexander Klein and Christopher M. Meissner report in Did Tariffs Make American Manufacturing Great? New Evidence from the Gilded Age (NBER Working Paper 33100).

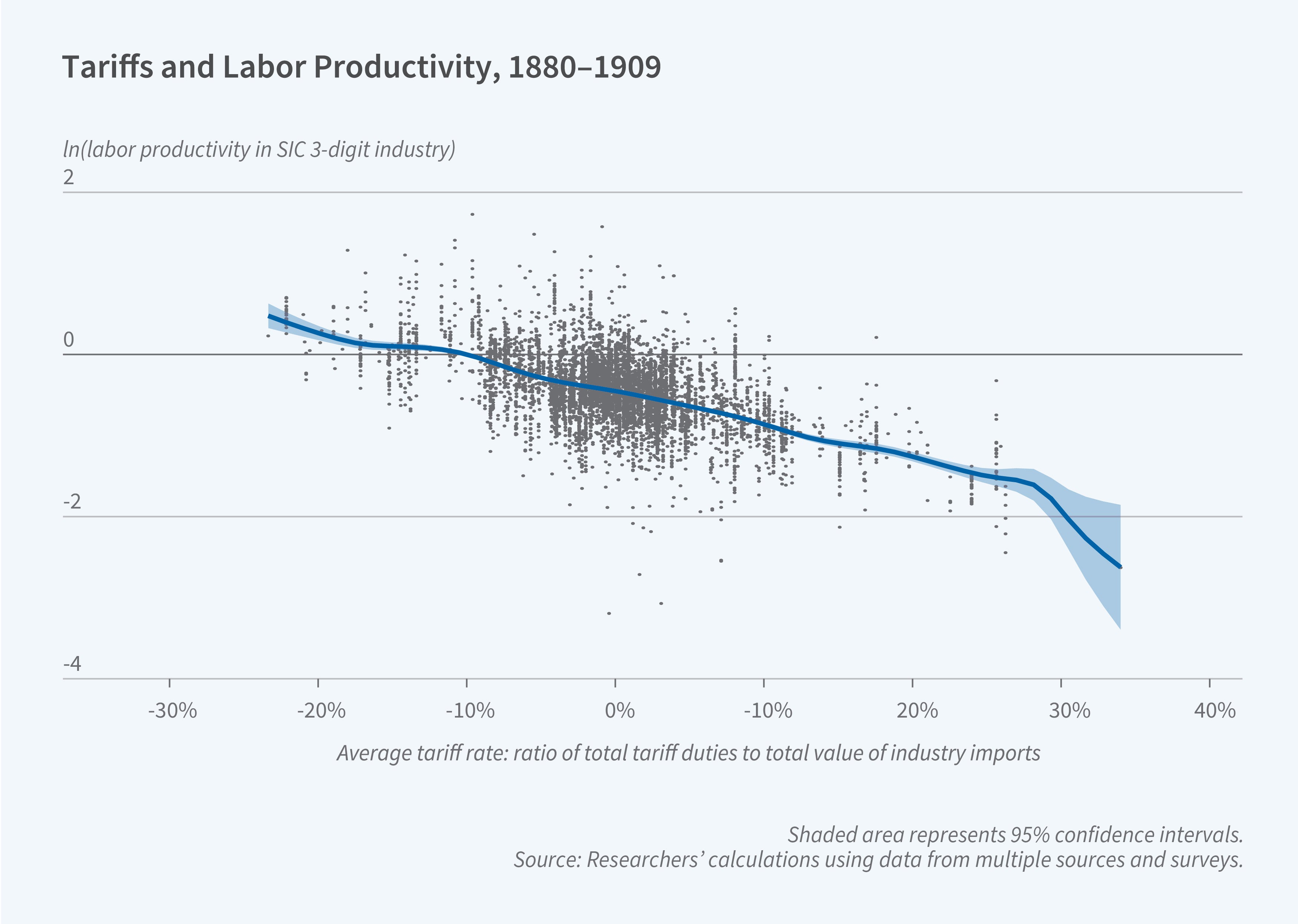

Tariffs on imported manufactured goods between 1870 and 1909 were associated with reduced labor productivity in domestic industries.

The researchers find that at the industry level, higher tariffs were associated with reduced labor productivity, greater total output, more establishments, and more workers. They also find that higher tariffs were associated with lower output per establishment, suggesting that higher tariffs led to the entry of smaller, less productive firms.

The effects of tariffs varied significantly across industry subcategories. The negative effects were larger than in the manufacturing sector as a whole in industries such as advanced chemicals like rubber, oil, and dyes, and textiles and apparel. A small set of two dozen industries that were at the vanguard of the “second industrial revolution” exhibit some positive effect of tariffs on labor productivity, but there is still some uncertainty given the large standard errors on these coefficients. Moreover, the importance of these sectors in overall production was small, so the effect of a high tariff regime on overall labor productivity in manufacturing would likely also have been small.

To conduct their analysis, the researchers developed a novel database of product-level tariffs. They digitized tariff information from the Foreign Commerce and Navigation of the United States for various fiscal years between 1869 and 1900. Product names from the data source were standardized, and products were assigned unique Standard International Trade Classification codes to enable analysis at the industry level. Then, they matched the industry-level tariff data to industry-state-level manufacturing information drawn from the US Census of Manufactures for 1870, 1880, 1890, 1900, and 1909.

To avoid confounding cause and effect, the researchers focus on specific tariffs — tariffs specified as a fixed levy per unit of imports. The ratio of the revenue from a specific tariff to the tariff-inclusive price of an imported good, a measure of the tariff rate in percentage terms, varies when the price of the foreign good changes. Foreign price changes can therefore be used as a source of exogenous tariff variation that is not related to potentially endogenous changes in tariff policy, which might be affected by industry conditions and lobbying efforts. These methods reveal some evidence consistent with the idea that industries comprised of politically influential firms were more successful in lobbying for tariff increases.

— Emma Salomon

The researchers are grateful for funding from NSF grant # 2314696 and the UC Davis Levine Funds.