The French (Trade) Revolution of 1860: A Win-Win Liberalization

When tariffs fell, instead of losing market share to Great Britain and becoming a net importer, France was able to sustain global sales even as imports surged.

While in exile in Britain in the 1830s, France's Louis Napoléon had a ringside seat as his host country took its first steps toward liberalizing trade. He liked what he saw, and envisioned jumpstarting the French economy by eliminating trade barriers and lowering tariffs.

When he became emperor in 1852, Napoléon III found that leading industrialists staunchly defended protectionist trade laws, fearing that without them they would lose market share to foreign competition. After consolidating power, he assigned Michel Chevalier to undertake secret negotiations with the British to dramatically reduce trade barriers. The result, the Cobden-Chevalier Treaty of 1860, was "a watershed in the history of modern international trade," according to Stéphane Becuwe, Bertrand Blancheton, and Christopher M. Meissner, who have analyzed this treaty's impact in International Competition and Adjustment: Evidence from the First Great Liberalization (NBER Working Paper 25173).

Because the treaty was concluded without direct input from commercial interests, it came as a shock. Nevertheless, French industry adapted smoothly to the new competitive environment. Studying these effects may provide insights on the consequences of trade policy changes both today and in the first wave of globalization.

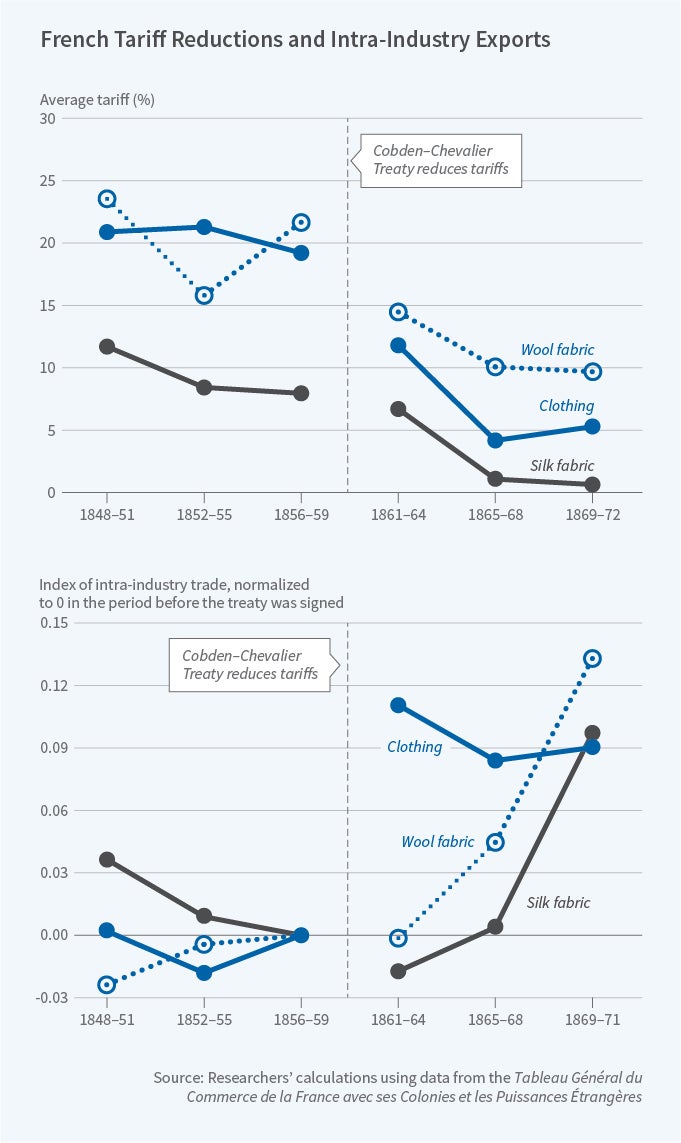

In 1860, Great Britain and France were the world's largest and second-largest exporters. France had banned imports of the great majority of woolen and cotton fabrics. A common fear was that without these protections, more-efficient British competitors would gain market share at the expense of domestic producers. But the doomsday predictions did not materialize. Supported by government adjustment loans, French producers upgraded their operations, diversified their export base and differentiated their product lines. Intra-industry trade patterns adjusted, allowing for a smooth adjustment to the new trade environment. "Instead of losing market share to Great Britain and moving towards net import status," the researchers find, "France was able to sustain global sales even as imports surged." In contrast, they note, an inter-industry response to falling tariffs would have involved disruptive, large-scale reallocation of labor and resources.

Intra-industry trade as a share of total French trade tripled between 1859–60, when it accounted for about 14 percent of trade, and 1872, when it accounted for 38 percent. While some products lost market share, French factories survived and thrived by producing unique brands. The researchers point out that the sectors that concerned protectionists most — cotton, wool, and silk cloth — did see intensified competition, but exports and imports rose together.

In the wake of the Cobden-Chevalier Treaty the French signed commercial pacts with more than half a dozen other nations. These, too, were associated with increases in the share of trade accounted for by intra-industrial products. The researchers conclude that these reforms benefited both French industry and French consumers. "French industry and trade seems to have remained buoyant. ...French consumers are also likely to have gained through a higher variety of products available and at lower cost."

— Steve Maas