A Long-Run Reevaluation of War on Poverty Programs

Over sixty years ago in 1964, the launch of the War on Poverty represented one of the largest and most comprehensive attempts to improve wellbeing in US history. President Lyndon Johnson’s administration invested billions of dollars in American education, health, employment, and community development.1 Many of these programs targeted the roots of poverty, seeking to provide a “hand up, not a handout.” Johnson aimed “not only to relieve the symptom of poverty, but to cure it and, above all, to prevent it.”2

My research with collaborators digs deeper into the workings of specific War on Poverty programs, seeking evidence about their effects on generational poverty and economic mobility. Our long-run perspective takes advantage of newly available data. Large-scale data from the Census Bureau and the Social Security Administration allow for a more comprehensive look at how access to programs for children in the 1960s and 1970s shaped the health, education, employment outcomes, and living circumstances of tens of millions of adults today. Moreover, the hurried, local implementation of the same program in different communities offers opportunities for credible causal inference.3 These evaluations are not case studies of policies in controlled conditions but analyses of hundreds of on-the-ground programs across the US.

Early Childhood Investments Through Head Start

This long-run perspective is particularly important when evaluating early childhood programs, which aimed at preventing adult poverty. Launched in 1965, Head Start is one of the most popular War on Poverty programs and serves over 1 million children today. Since the 1960s, the program has offered an early education curriculum to preschool- and kindergarten-aged children and has also gone further, providing nutritious meals, screenings for childhood diseases as well as vision and hearing problems, and referrals to health and social services. For example, Head Start tests children’s eyesight and hearing and refers them for glasses or hearing aids as needed. Head Start’s goal is to help kids from less advantaged backgrounds start school on an equal footing, setting them up for success in first grade and beyond.

For much of the program’s history, evaluating its success in helping children escape poverty vexed researchers. Early evaluations of the program did not have valid comparison groups: Children whose parents enrolled them in the program would likely have had different school outcomes than similarly disadvantaged peers whose parents did not, even without the program. The more recent Head Start Impact Study, which used a randomized controlled trial to evaluate the program, underestimated the extent to which parents in the control group would enroll their children in other preschool programs, making it difficult to determine the program’s effects.

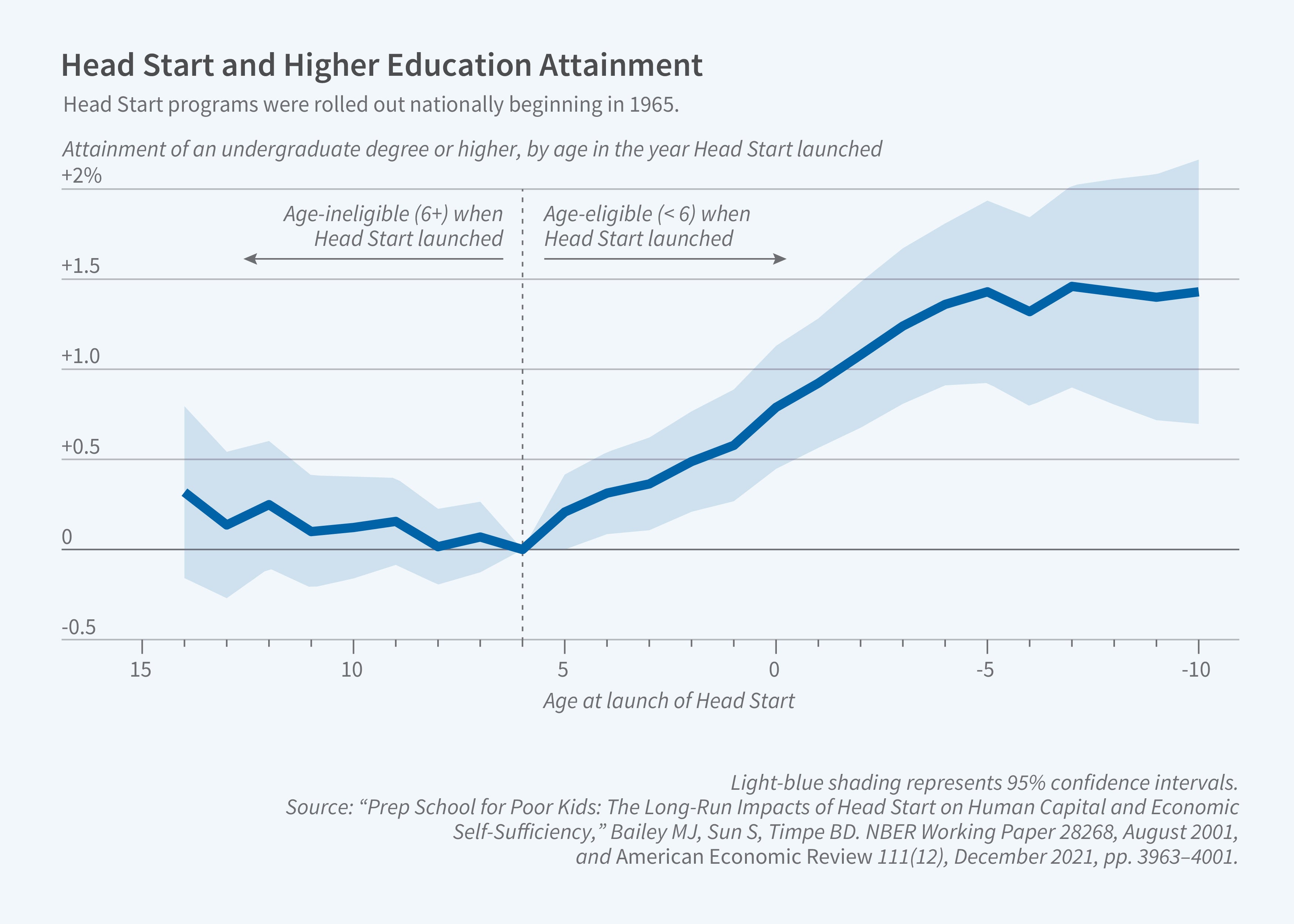

Our work tackles these issues by measuring Head Start’s success according to children’s later life educational attainment, work in professional occupations, participation in the labor force, and wage earnings.4 Using Head Start’s launch in the 1960s also allows for a compelling research design. Although children reaching first grade around the time of Head Start’s launch entered the same schools, had parents working in the same labor markets, and faced similar state policies, they were born a few months too soon to enroll in the program. These slightly older children lacked good alternative preschools and kindergarten options when Head Start was not available.

Using these slightly older children as a comparison group allows us to characterize how Head Start affected the lives of its early enrollees. The results show that Head Start children were significantly more likely to finish high school and enroll in and finish college than their peers who were entering first grade (Figure 1). The results also show that cohorts with access to Head Start experienced lower rates of adult poverty, worked more in the labor market, and were less likely to have received public assistance. We also find suggestive evidence that Head Start’s long-run effects are driven by many factors beyond a preschool curriculum, including health screenings and referrals and more nutritious meals. In short, Head Start’s effects show up decades later in increased productivity and wellbeing. These gains for individuals have substantial fiscal externalities, translating into a larger base of taxpayers and lower public expenditures. Complementary work shows that Head Start continued to benefit the children of its early enrollees.5

Improving Food Security and Nutrition Through Food Stamps

The Food Stamps Program is another large national program that expanded during the War on Poverty. Known today as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), the Food Stamps Program was designed to help low-income families meet their food and nutrition needs, providing paper coupons to help families purchase groceries. In 1964, legislation expanded the Food Stamps Program from a small pilot program in depressed agricultural areas into a core component of the US safety net. Today, SNAP is one of the largest anti-poverty programs for children in the United States, providing assistance to nearly 42 million Americans.

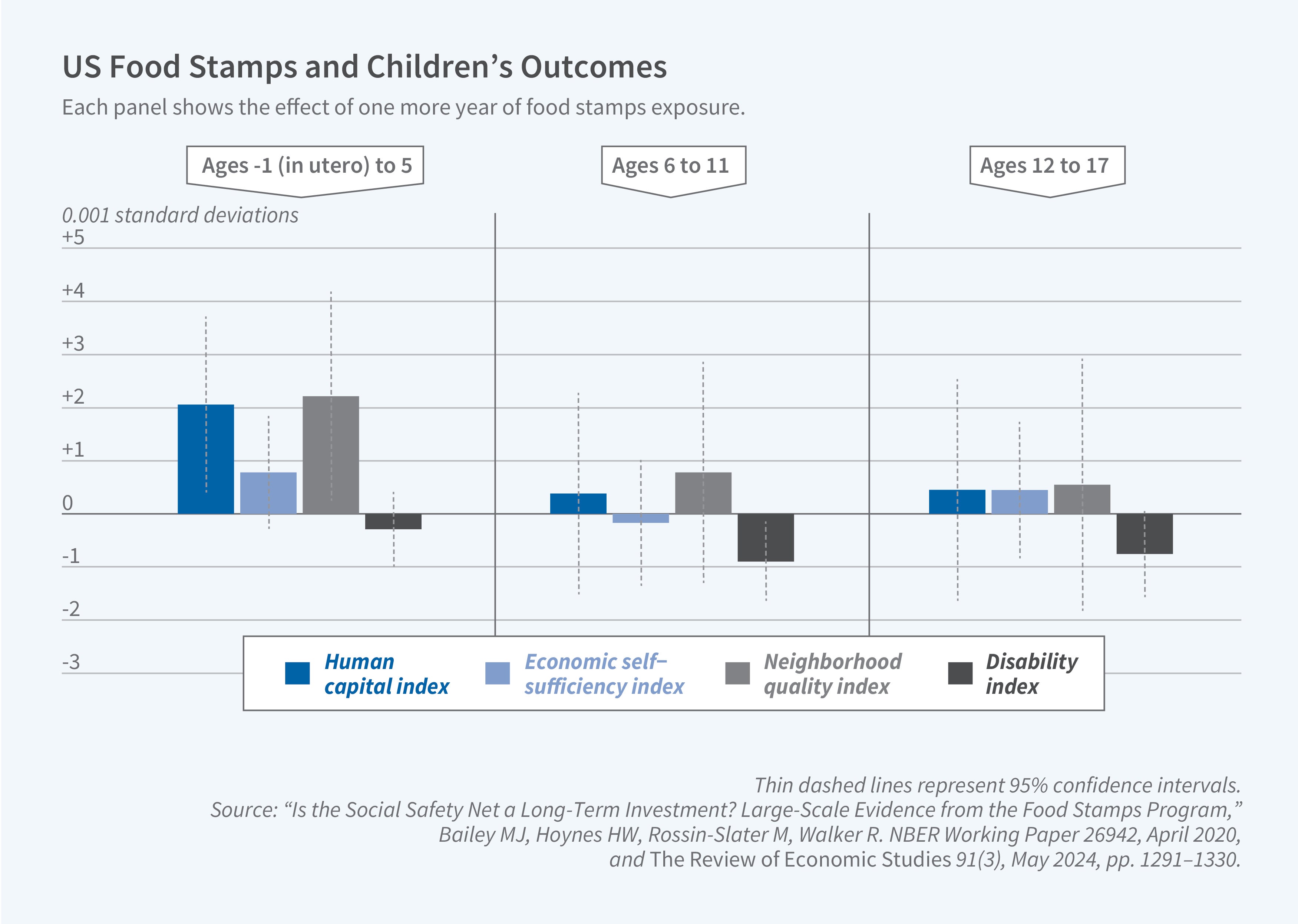

Our research examines how the timing and duration of early food stamps access shaped health, human capital, economic self-sufficiency, and neighborhood quality.6 Figure 2 shows that greater access to food stamps in early life (in utero to age 5) is associated with significant increases in human capital (i.e., educational attainment and professional occupation), economic self-sufficiency (i.e., work intensity and earning enough to exit poverty), neighborhood quality, and reductions in physical disability. In contrast, we find that exposure to food stamps during primary school (ages 6–11) and secondary school (ages 12–17) had larger effects on reducing disability but smaller effects on the other dimensions of wellbeing. The results show not just that public investments in the social safety net benefited children in the long run but also help pinpoint at what ages these investments mattered.

Family Planning Programs Facilitate Investment in Children

Another of the War on Poverty’s novel policy approaches to empowering parents and increasing resources for children was through funding family planning programs. President Richard Nixon summed up the consensus view of the time, stating that “unwanted or untimely childbearing is one of several forces which are driving many families into poverty or keeping them in that condition.”7

The architects of the War on Poverty viewed the price of reliable contraceptives as a barrier to reducing poverty and promoting children’s opportunities. Of particular concern was that the “pill,” the first oral contraceptive, was prohibitively expensive in the 1960s — roughly twice today’s annual cost and equivalent to more than three weeks of full-time work at the 1960 minimum wage (without factoring in the cost of a physician visit). Numerous studies at the time documented that poor women were less likely to use effective contraceptives and had more children than women in families with higher incomes. The goal of federal family planning programs was to equalize access to contraception, allowing everyone to plan their families and escape poverty.

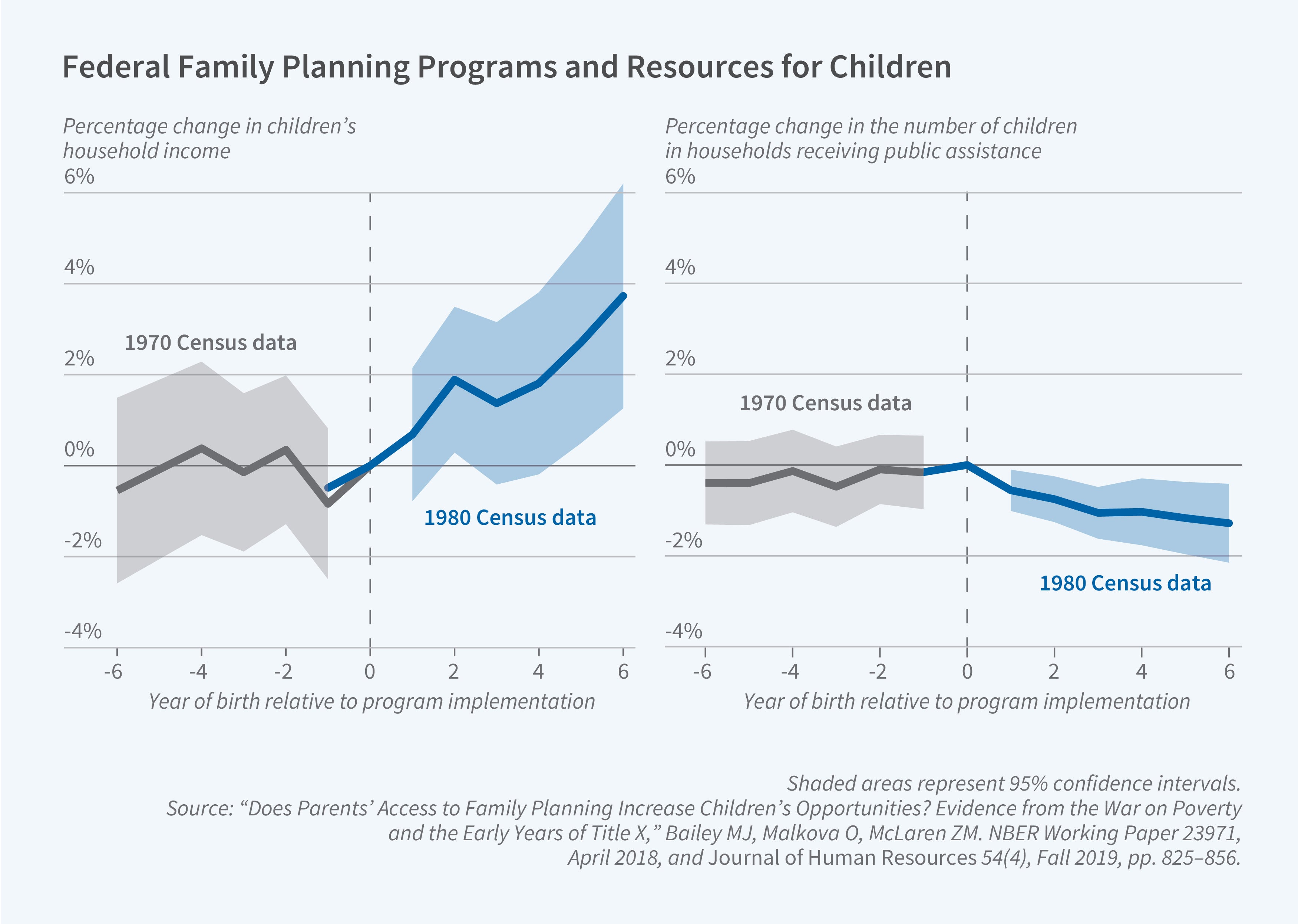

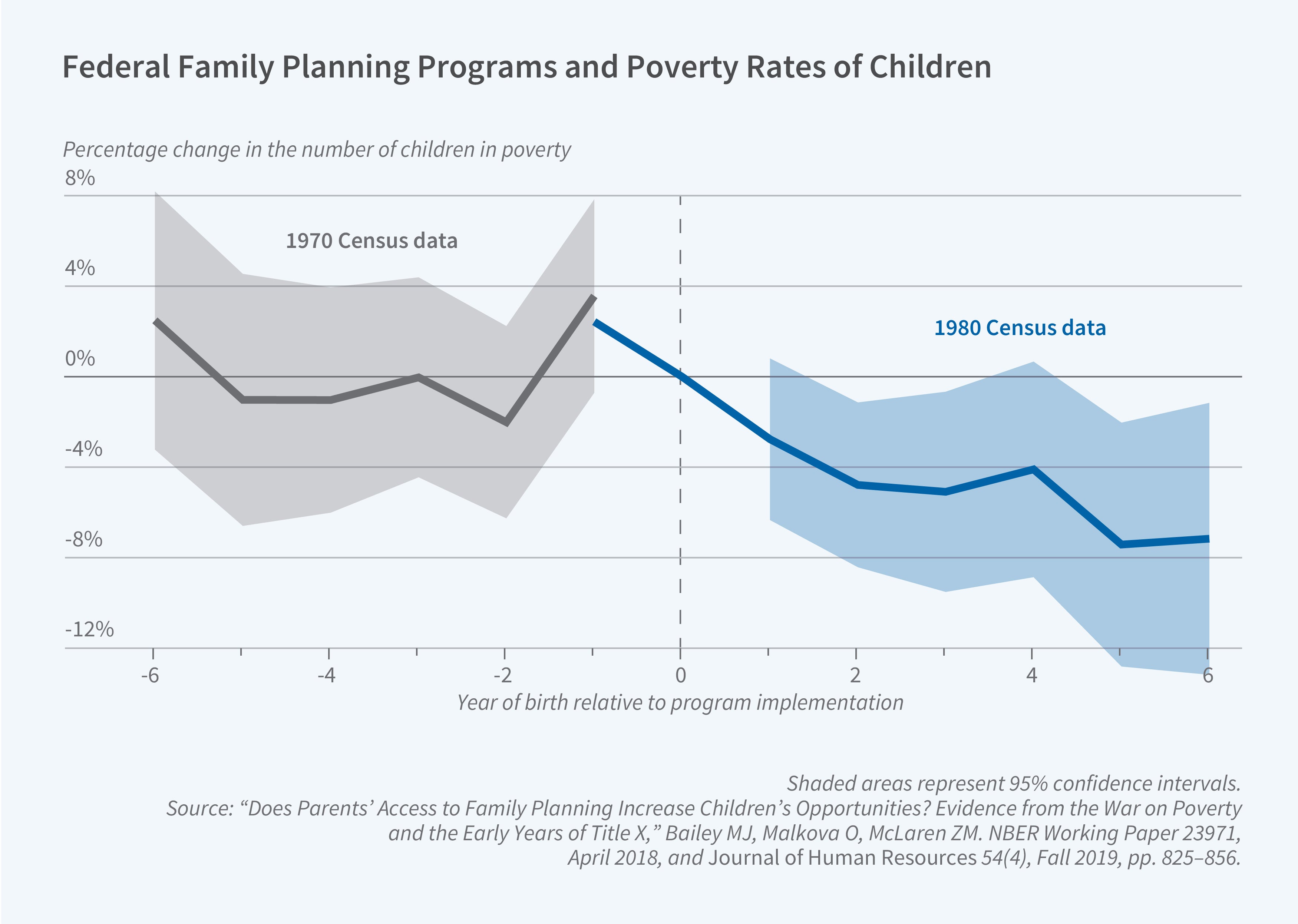

Our research assembles new evidence regarding how federal family planning programs affected children’s resources and long-run outcomes. Using these programs’ start dates in different communities in the 1960s, we find that these policies not only reduced fertility rates8 but also increased children’s resources during childhood (Figure 3)9 and improved their outcomes as adults decades later, including college completion, labor force participation, wages, and family income.10 Our research suggests that the main mechanism for these effects is not the prevention of childbearing but its delay. Delaying childbearing allowed parents to find more stable partners and better-paying jobs, reduce their dependence on public assistance, and decrease their likelihood of being in poverty. Consequently, children born in better conditions had more resources and more opportunities.

Delivering Primary Care Through Community Health Centers

Today’s federally qualified health centers, previously known as community health centers (CHCs), were another part of the War on Poverty’s network of preventive community programs. Unlike this era’s large public insurance expansions (e.g., Medicare and Medicaid), CHCs used federal funds to deliver primary and preventive care to underserved populations. Serving both insured and uninsured patients, CHCs charged on a “pay as you can” sliding scale for services and medications, were located in disadvantaged neighborhoods to increase convenience, and offered in-home visits and transportation to appointments.

Today, over 12,000 CHC sites operate in every state and serve over 32 million Americans. Ninety percent of these patients have incomes under the federal poverty line, 50 percent are covered by Medicaid, and 20 percent are uninsured. In 2010, the Affordable Care Act appropriated $11 billion over five years to expand CHC infrastructure to serve the millions of Americans gaining health insurance under its provisions.

The expansion of CHCs was driven by the belief that they improve access to primary care and help control healthcare costs.

Our work on CHCs in the 1960s provides a rare opportunity to evaluate this claim, both in the short and long run.11 We find that the launch of a CHC is associated with significant declines in age-adjusted mortality, particularly from cardiovascular disease among adults over 50. These reductions in mortality were highly persistent, decreasing the gap in mortality between the poor and non-poor by 20 to 40 percent for 25 years. Some of the long-term benefits of CHCs went to adults who were ineligible for Medicare (aged 50 to 64), but the program achieved its largest mortality reductions among those with Medicare coverage — without an accompanying increase in Medicare spending. This is likely because CHCs reduced the cost of prevention, diagnosis, and management of chronic conditions while also providing free or substantially discounted prescription medications.

Conclusion

The War on Poverty’s programs — and the political backlash — continue to shape policy debates in the US. Although poverty declined over the 1960s, its persistence is often regarded as evidence that anti-poverty policy cannot be effective, or worse, does harm. President Ronald Reagan famously quipped in his 1988 State of the Union Address that “the federal government declared war on poverty, and poverty won.”

This broad framing has dominated political discussions for decades, but it misses deeper lessons about the positive role that specific programs and policies may play. Over the past 60 years, structural shifts in families and labor markets have contributed to increased poverty rates. Many of the War on Poverty’s programs and policies worked against these headwinds which reduced the odds of upward economic mobility, increasing health and human capital, and improving labor market outcomes. The counterfactual is that US poverty rates, health, human capital, and employment outcomes would have been worse today without the substantial investments made under the War on Poverty.

A crucial aspect of evidence-based policy formulation is evaluating the returns on any dollars spent. For example, how does government spending on a program compare to the benefits received by individuals or by the government directly through taxes or decreased spending? The marginal value of public funds (MVPF) framework measures the efficiency of public spending by comparing program benefits to net government costs.12 Our analyses of the War on Poverty period suggest that Head Start and family planning programs had an infinite MVPF — that is, the programs had a net zero fiscal cost and generated revenue, more than paying for themselves. The Food Stamps Program had an MVPF of 62, meaning its benefits far exceeded its costs.

Our research demonstrates that several War on Poverty programs successfully reduced poverty and improved wellbeing. In addition, these programs generated fiscal benefits for nonparticipants by boosting tax revenue and lowering spending on public assistance. While our analyses are not a full accounting of War on Poverty programs, nor do their lessons fully generalize to the present, our research underscores the power of well-designed policies to improve upward mobility and enhance wellbeing for future generations.

Endnotes

“Legacies of the War on Poverty,” Bailey MJ, Danziger S, editors. The National Poverty Center Series on Poverty and Public Policy. New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2013.

“Annual Message to the Congress on the State of the Union,” Johnson LB. The American Presidency Project, January 8, 1964.

“How Johnson Fought the War on Poverty: The Economics and Politics of Funding at the Office of Economic Opportunity,” Bailey MJ, Duquette NJ. NBER Working Paper 19860, September 2014, and The Journal of Economic History 74(2), June 2014, pp. 351–388.

“Prep School for Poor Kids: The Long-Run Impacts of Head Start on Human Capital and Economic Self-Sufficiency,” Bailey MJ, Sun S, Timpe BD. NBER Working Paper 28268, August 2021, and American Economic Review 111(12), December 2021, pp. 3963–4001.

“Breaking the Cycle? Intergenerational Effects of an Antipoverty Program in Early Childhood,” Barr A, Gibbs CR. Journal of Political Economy 130(12), December 2022, pp. 3253–3285.

“Is the Social Safety Net a Long-Term Investment? Large-Scale Evidence from the Food Stamps Program,” Bailey MJ, Hoynes HW, Rossin-Slater M, Walker R. NBER Working Paper 26942, April 2020, and The Review of Economic Studies 91(3), May 2024, pp. 1291–1330.

“Special Message to the Congress on Problems of Population Growth,” Nixon R. The American Presidency Project, July 18, 1969.

“Reexamining the Impact of Family Planning Programs on US Fertility: Evidence from the War on Poverty and the Early Years of Title X,” Bailey MJ. NBER Working Paper 17343, August 2021, and American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 4(2), April 2012, pp. 62–99.

“Does Parents’ Access to Family Planning Increase Children’s Opportunities? Evidence from the War on Poverty and the Early Years of Title X,” Bailey MJ, Malkova O, McLaren ZM. NBER Working Paper 23971, April 2018, and Journal of Human Resources 54(4), October 2019, pp. 825–856.

“Fifty Years of Family Planning: New Evidence on the Long-Run Effects of Increasing Access to Contraception,” Bailey MJ. NBER Working Paper 19493, October 2013, and Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Spring 2013, pp. 341–395.

“The War on Poverty’s Experiment in Public Medicine: Community Health Centers and the Mortality of Older Americans,” Bailey MJ, Goodman-Bacon A. NBER Working Paper 20653, March 2015, and American Economic Review 105(3), March 2015, pp. 1067–1104.

“Unified Welfare Analysis of Government Policies,” Hendren N, Sprung-Keyser B. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 135(3), August 2020, pp. 1209–1318.