The Global Decline in the Mental Health of the Young

One of the major findings in wellbeing research until recently was that happiness was U-shaped by age and unhappiness hump-shaped by age. There was a midlife crisis — a finding reported in well over 600 published papers using data on 145 countries. It was present in both developing and developed countries. And it was persistent over time. The finding of a peak in ill-being in midlife was consistent with Anne Case and Angus Deaton’s work on mortality and the so-called “deaths of despair.”1 In the US in particular and to a lesser extent in other countries, White prime-aged individuals without a college degree had high death rates from suicide, drug overdoses, and cirrhosis of the liver. Drug overdose deaths in the US, for example, peaked at midlife ages. In 2023, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported that overdose death rates per 100,000 by age rose from 13.5 for 15-to-24-year-olds to 45.6 for 25-to-34-year-olds and 60.8 for 35-to-44-year-olds, and then declined to 53.3 for 45-to-54-year-olds, 49.2 for 55-to-64-year-olds, and 14.7 for those over the age of 65.2 The morbidity data matched the mortality data.

This U-shaped happiness relationship, which several psychologists disputed, was the focus of much of my research for a number of years: It was even found in a study of great apes. I regarded it as one of the most striking and persistent patterns in social science. Until it wasn’t.

I first realized that the relationship between happiness and age had changed after listening to an interview with Jean Twenge on the Ezra Klein show in May 2023.3 The show started with some data; between 2011 and 2021 the number of teens and young adults with clinical depression had more than doubled. The claim was that there was a full-blown mental health crisis among young people. This was shocking to me, so I went back to the data to check it out. There it was. I had missed it.

Andrew Oswald and I had been working with data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) from the CDC. We had focused on despair, which was measured as those who answered 30 to the question “Now thinking about your mental health, which includes stress, depression, and problems with emotions, for how many days during the past 30 days was your mental health not good?” We had noted that what an editor insisted we call extreme distress had risen for the prime ages of 35–44 over the period 1993–2019, especially for less educated Whites and Native Americans of all ages.4 But we had not focused on the young. Their mental health has worsened sharply both absolutely and relatively in the last decade around the world.

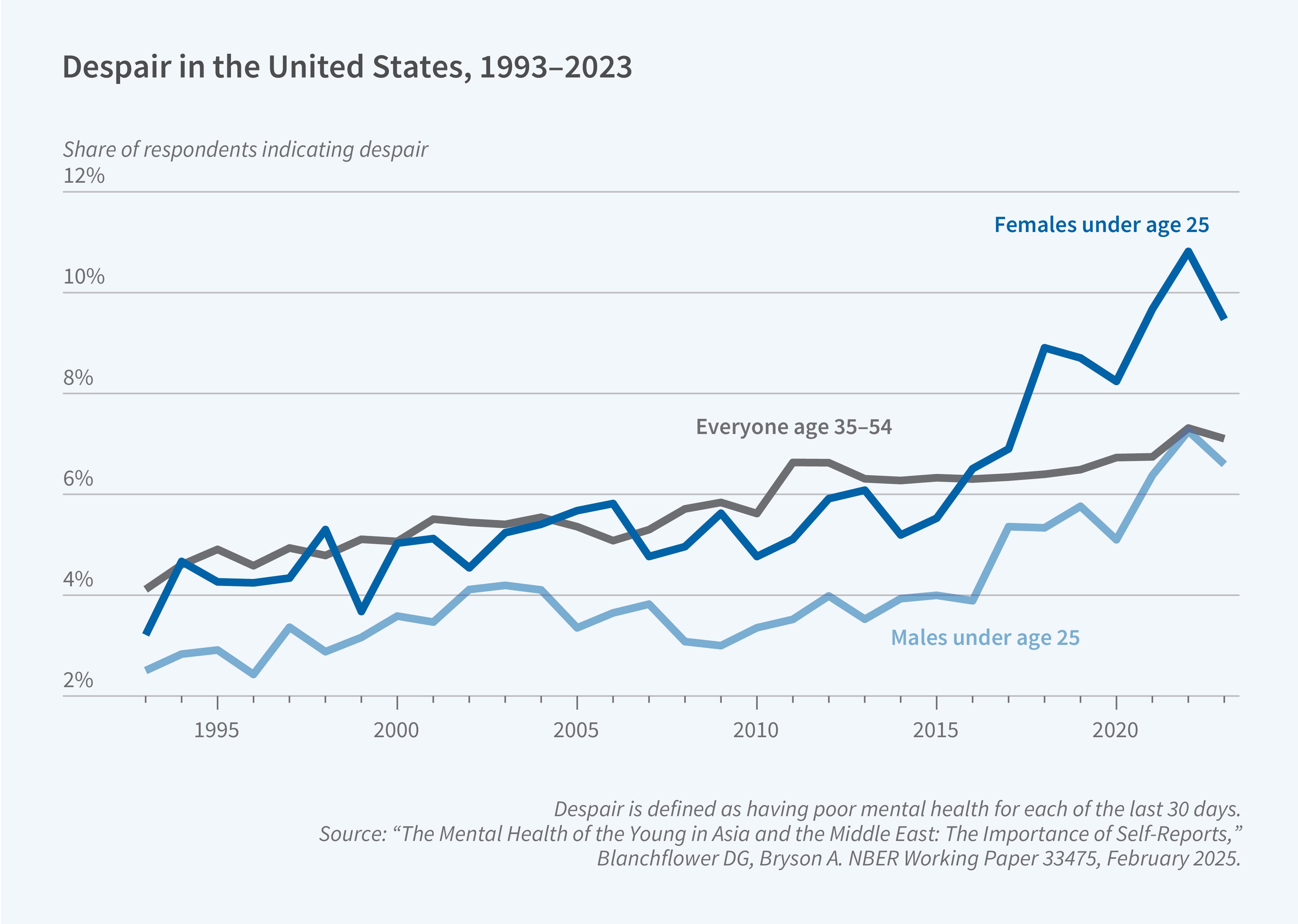

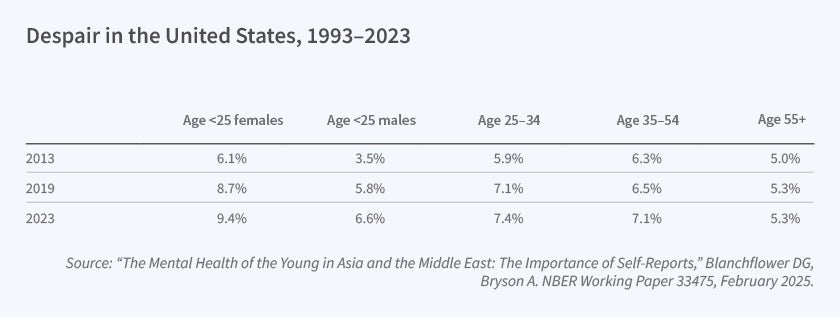

Since 2013 or so, despair has risen sharply for the young in general and young women in particular. Figure 1 illustrates and plots the time series of despair for the young by gender for ages 18–24 and then for ages 35–54. Despair among young females surpasses that among the prime age group in 2016 and the young males rate catches up in 2023. Rates for young men track those for young women but at lower rates. Despair rates are presented in Table 1.

The despair rates for young men and women in 1993 were below those of 25-to-54-year-olds, but by 2023 they were above them. The despair rates of individuals 55 and older changed little over this period.

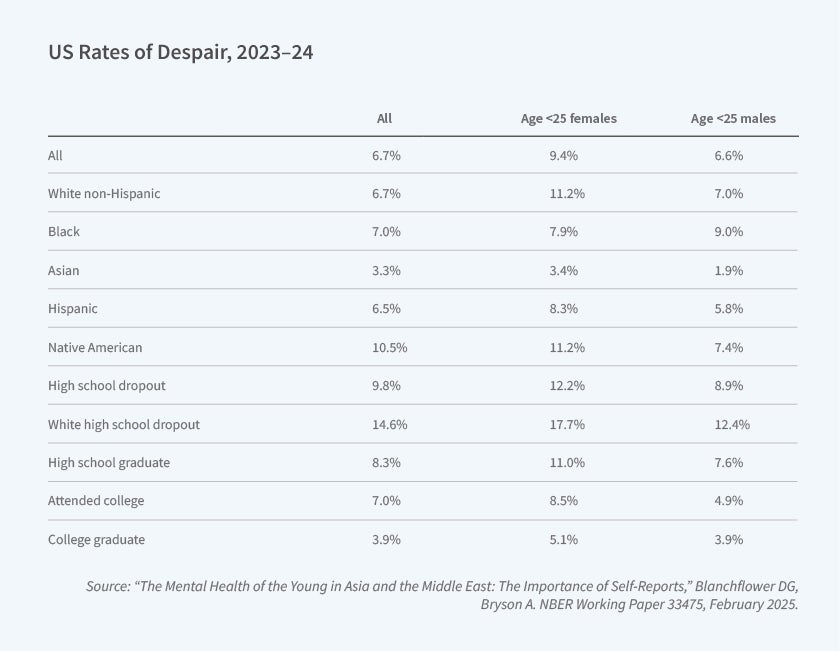

In the 2023/2024 BRFSS, the proportions in despair were 6.7 percent overall, 7.5 percent for females, and 5.8 percent for males (n = 425,215). The highest rates were for White female high school dropouts under the age of 25, where nearly one in five reported that every day of their lives was a bad mental health day.

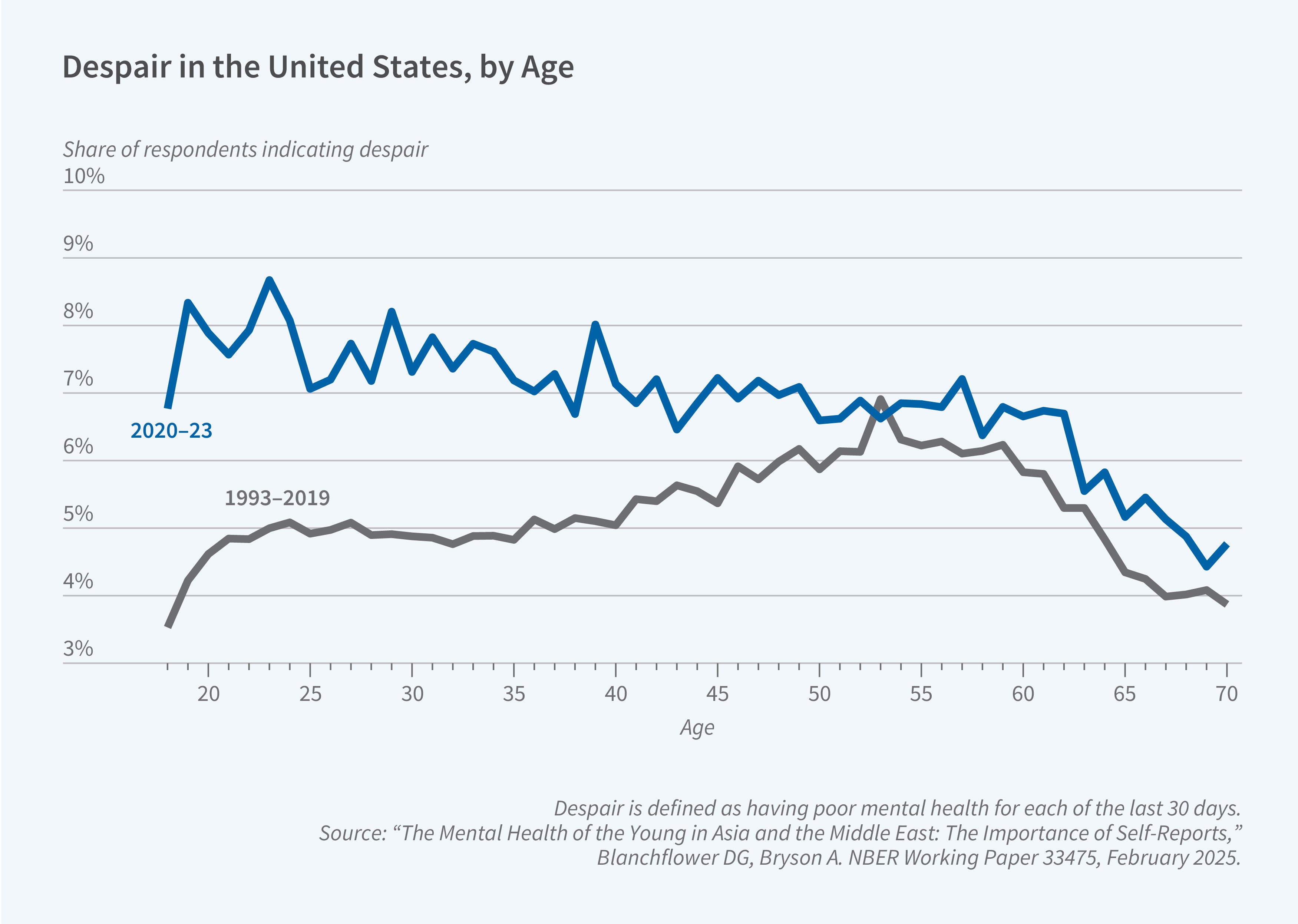

In Figure 2, I plot the weighted despair data by age, with a sample size of 8.4 million, for the US from 1993 to 2019.5 It gives the expected hump shape in despair, which peaks at age 53. I had failed to spot something else: The upward trend in despair of the prime age group had stopped around 2017, and from around 2013 or so the rates of despair for the young rose. Figure 2 also shows despair by age for the period 2020–24. The U-shape has gone and now despair declines with age. The despair levels of the group under the age of 50 have risen and especially so for those less than 25 years of age. As an example, at age 22, 4.8 percent were in despair in the earlier period versus 7.9 percent in 2020–23.

A recent dramatic worsening of youth mental health has been found in every major US data file, including the National Health Interview Survey, the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, the American National Election Studies, the US Household Pulse Surveys, the Healthy Minds Study, and the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS). In the YRBSS, for example, the proportion of high school students aged 14–18 saying that they had been “sad or hopeless every day for the last two weeks” rose from 21 percent (males) and 36 percent (females) in 1999 to 28 percent and 53 percent, respectively, in 2023, with most of the increase taking place since 2017.6

There is also evidence of rising youth suicide rates in the US since around 2015 as adult rates declined, as well as rises in antidepressant prescriptions for the young plus increases in emergency department visits related to mental health. In the US, from 2016 to 2019, emergency department visits with a principal diagnosis related to mental health only increased for ages 0–17, from 784 per 100,000 population to 869 per 100,000 population.7

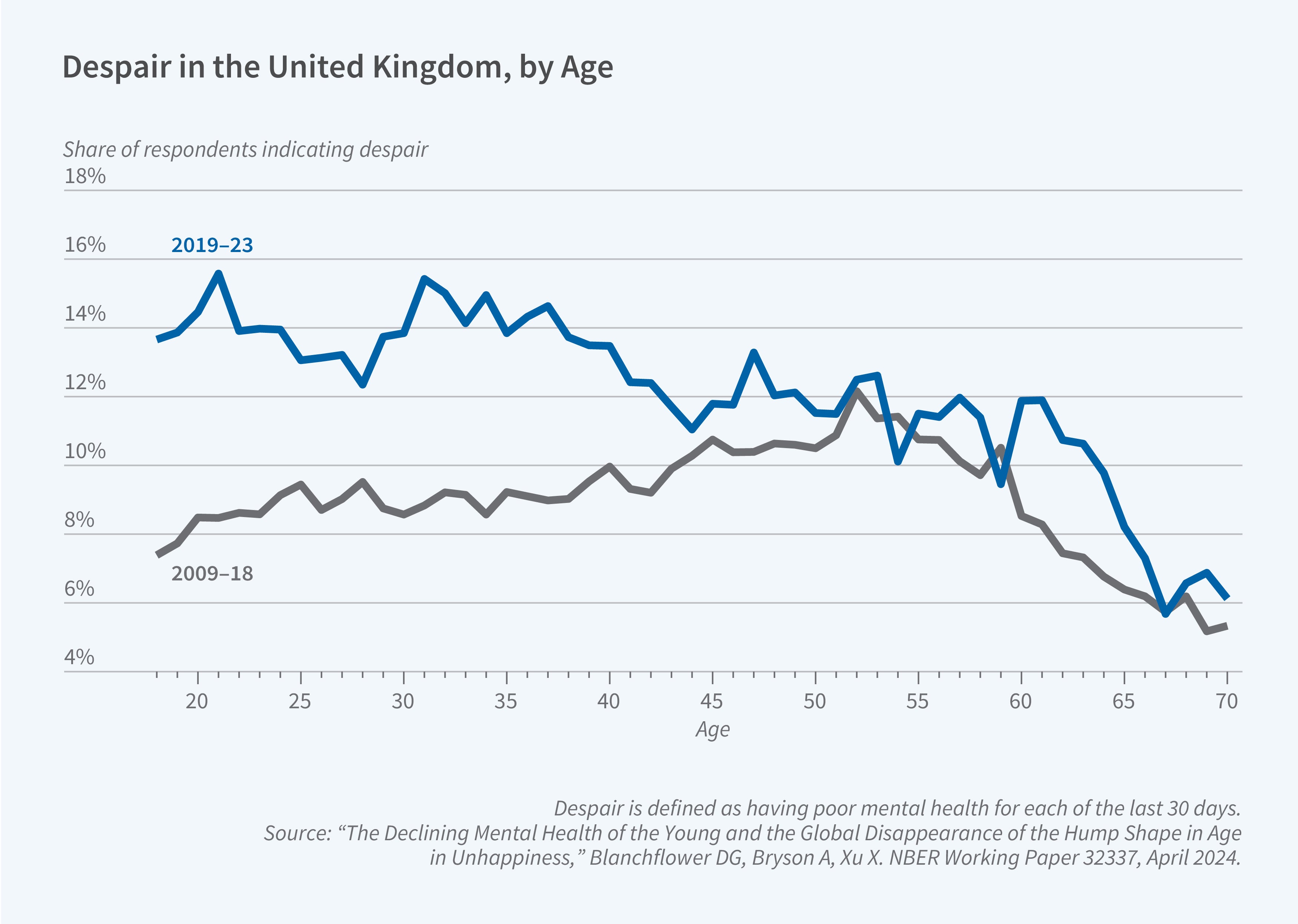

Data from other countries suggest similar patterns. Alex Bryson, Xiaowei Xu, and I report data for the UK from the Understanding Society panel on the 12-Item General Health Questionnaire score with values from 0 to 36 and here despair is defined as a score of 20 or higher.8 Figure 3 shows that, as in the US, the hump shape in ill-being by age that is notable in the earlier period (2009–18) has disappeared in the later period, 2019–23, and has been replaced by a profile of despair that is declining with age.

The United Nations Development Programme commissioned a series of papers to determine whether this phenomenon is global. David Bell, Bryson, and I have studied the UK;9 Anthony Lepinteur, Alan Piper, and I have studied France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and Sweden;10 and Bryson and I have studied ex-Soviet countries, Latin America, Africa, the Middle East, and Asia.11,12,13 The mental health of the young has worsened globally, and in work with Twenge I have shown this is especially the case in English-speaking countries — the UK, US, Australia, Canada, Ireland, and New Zealand.14

The finding of a youth mental health crisis across the world is especially strong in internet-based surveys, such as the EU Loneliness Survey of 2022, a subset of the Global Flourishing Study (2022–24 sample), and especially the Global Minds surveys of 2020–25 and the COME-HERE surveys of 2020–23 in Europe. In these surveys, we find that the young are the least happy and the most unhappy, wellbeing rises with age, and ill-being declines with age. We also found this in a telephone Flash Barometer survey for Europe in 2022. Indeed, we found broad evidence across 167 of the UN’s 193 countries.15 In each of these countries, an age 18–24 dummy was significantly negative in a positive affect equation using the Mental Health Quotient score. Results were the same with other wellbeing variables. We also found consistent evidence in many countries of declining wellbeing of 15-year-olds in the OECD’s PISA surveys, which are self-reported.

The evidence is much weaker when traditional social surveys — where interviewers collect data either face-to-face or by phone — are examined, including the Gallup World Poll, the Eurobarometer, the Latinobarometer, the Afrobarometer, the World Values Survey, the European Social Survey, UNICEF’s Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys, EBRD’s Life in Transition Surveys, and the International Social Survey Programme. In these surveys, the finding of low wellbeing of the young is much more apparent in negative affect variables such as anxiety and depression than it is in positive affect variables such as happiness and life satisfaction. Government surveys around the world, such as the Labour Force Survey in the UK, are facing challenges with high nonresponse of the young.

I explored cross-country differences by examining the Global Flourishing Study of 2022–24 across 22 countries that used both telephone and web-based surveys.16 The results showed rising wellbeing with age in the internet surveys and declining wellbeing with age in the telephone surveys. The survey and question modes used matter as the young don’t seem to answer the phone, and when they do, they tell interviewers differently and are more positive on mental health than if they self-report — there is, thus, evidence of social desirability response bias. The global mental health crisis of the young is picked up especially in self-reports. There is no contradiction in the results of these internet surveys regarding positive or negative affect variables.

The decline in the mental health of the young started in the second decade of the twenty-first century, is global, and disproportionately impacts young women. Some have argued the rise in smartphone use and the availability of the internet fit these facts well. My research suggests a clear association between the number of hours of the day spent on a smartphone, the age at which a child first got a cellphone, and poor mental health.

Others have suggested alternative explanations, including the Great Recession, changes in stigma over mental health issues, and different rules for mental health hospitalizations or even for what constitutes a suicide, but nobody has been able to show much of this empirically. It is hard to understand how this applies across the world in all cultures and languages and why it applies particularly to the young. The young are not joining youth clubs or the Scouts, playing sports, have less desire than in the past for spending time with others, and have increased material aspirations.

The iPhone was unveiled in January 2007 and 4.7 million phones were sold in the third quarter of 2008, and the iPad was launched in January 2010.17 Sales of smartphones worldwide rose from 122 million in 2007 to 297 million in 2010, 970 million in 2013, 1.2 billion in 2014, and 1.5 billion a year since 2018, and 40 million smartphones a quarter are now being sold in Africa. The timing is right! According to the YRBSS, in 2021, 36 percent of high school males ages 14–18 had screen time of at least five hours a day compared with 43 percent of females, up from 19 percent and 21 percent in 2013, respectively.

Further research is clearly needed to understand the source of the global decline in the mental health of the young and how potential policy or other actions can respond to it.

Endnotes

“The Great Divide: Education, Despair and Death,” Case A, Deaton A. NBER Working Paper 29241, September 2021, and Annual Review of Economics 14(1), April 2022, pp. 1–21.

“Drug Overdose Deaths in the United States, 2003–2023,” Garnett MF, Miniño AM. NCHS Data Brief No. 522, December 2024. National Center for Health Statistics.

“Transcript: Ezra Klein Interviews Jean Twenge,” New York Times, May 19, 2023.

“The Mental Health of the Young in Asia and the Middle East: The Importance of Self-Reports,” Blanchflower DG, Bryson A. NBER Working Paper 33475, February 2025.

“Declining Life Satisfaction and Happiness Among Young Adults in Six English-Speaking Countries,” Twenge J, Blanchflower DG. NBER Working Paper 33490, February 2025.

“The Declining Mental Health of the Young and the Global Disappearance of the Hump Shape in Age in Unhappiness,” Blanchflower DG, Bryson A, Xu X. NBER Working Paper 32337, April 2024.

“The Declining Mental Health of the Young in the UK,” Blanchflower DG, Bryson A, Bell DNF. NBER Working Paper 32879, August 2024.

“Further Evidence on the Global Decline in the Mental Health of the Young,” Blanchflower DG, Bryson A, Lepinteur A, Piper A. NBER Working Paper 32500, May 2024.

"The Mental Health of the Young in Ex-Soviet States,” Blanchflower DG, Bryson A. NBER Working Paper 33356, January 2025.

“The Mental Health of the Young in Latin America.” Blanchflower DG, Bryson A. NBER Working Paper 33111, November 2024.

“The Mental Health of the Young in Africa,” Blanchflower DG, Bryson A. NBER Working Paper 33280, December 2024.

“Declining Life Satisfaction and Happiness Among Young Adults in Six English-Speaking Countries,” Twenge J, Blanchflower DG. NBER Working Paper 33490, February 2025.

“Declining Youth Wellbeing in 167 UN Countries. Does Survey Mode or Question Matter?” Blanchflower DG. NBER Working Paper 33415, January 2025.

“Further Evidence on the Global Decline in the Mental Health of the Young,” Blanchflower DG, Bryson A, Lepinteur A, Piper A. NBER Working Paper 32500, May 2024.