Gender, Work, and Family: Progress and Ongoing Challenges

How do societal norms, public policies, and economic forces shape outcomes for men and women? My recent work, with several collaborators, addresses how gender disparities in labor markets influence individual opportunities, household decisions, and overall economic productivity. It brings together insights from long-term historical trends and the extensive gender literature to examine both progress and persistent challenges to gender equality.

Narrowing Gaps, Persistent Inequalities

The remarkable progress of women in the labor market marks one of the most significant economic and social changes of the past 75 years across many developed economies. Jessica Pan, Barbara Petrongolo, and I recently reviewed the vast body of work studying women’s changing roles in the economy and the underlying driving forces behind these developments.1

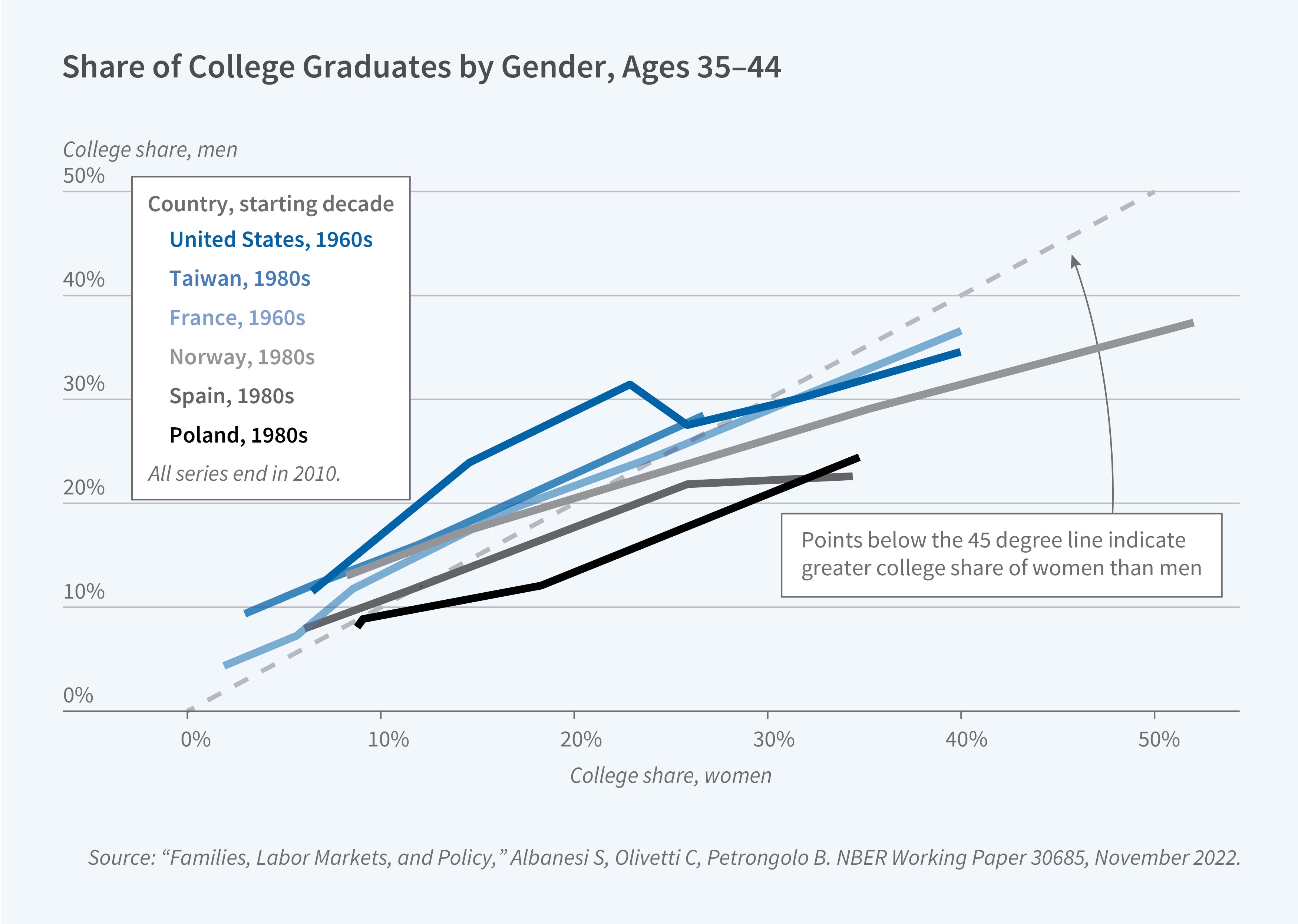

A widely documented trend is the female gain in human capital accumulation, leading to narrowing and then reversing gender gaps in college completion rates. In the 2010s, more women than men had a college education in all but one of the 24 countries that Stefania Albanesi, Petrongolo, and I studied in a recent analysis of cross-country gender trends and family policies.2

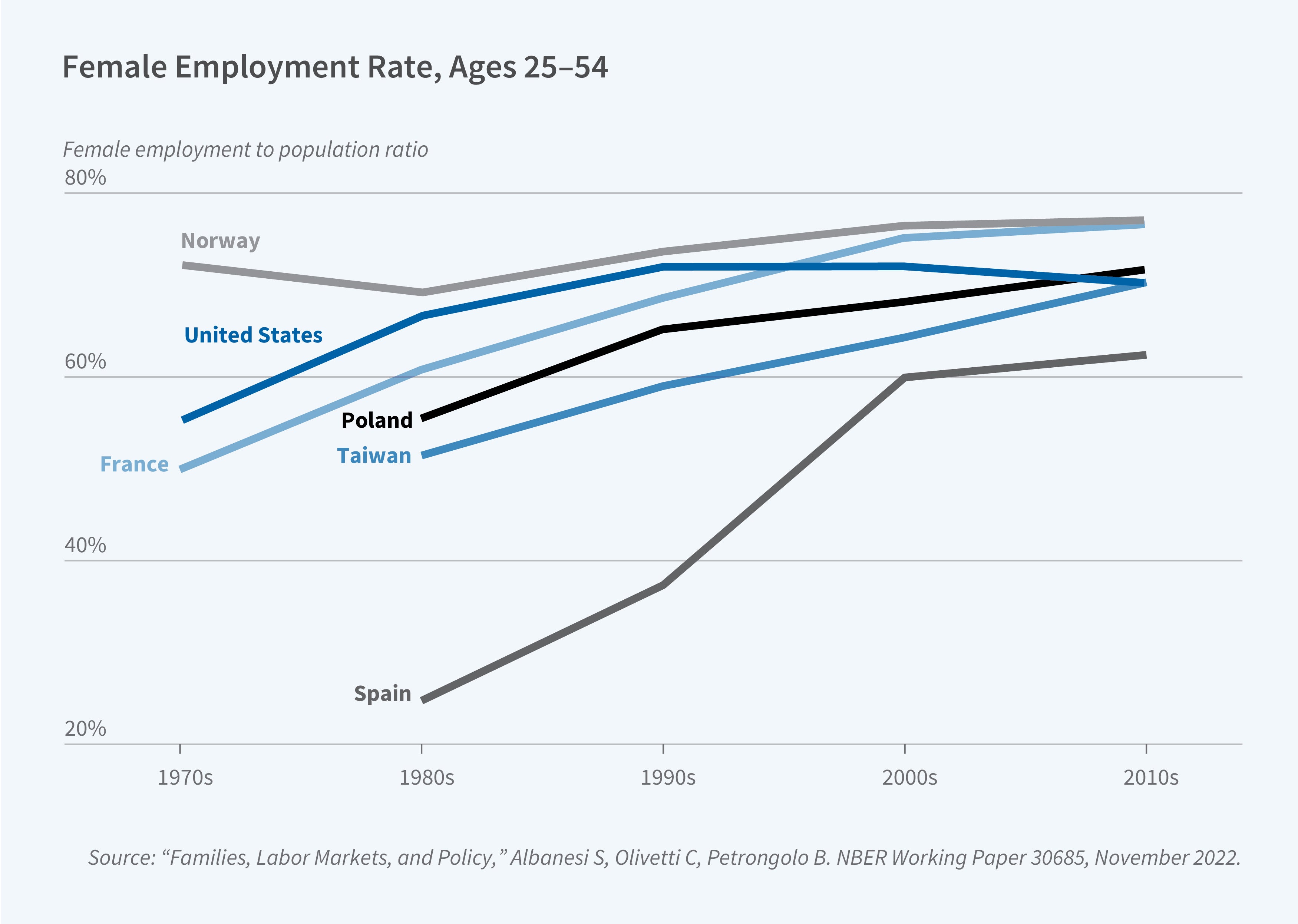

Women’s labor force participation has increased substantially in many countries, with some variation in the pace of change. As women’s labor market experience increased, their college majors became more relevant to their employment and their education and professional degrees expanded. Women delayed marriage, had fewer children, and entered traditionally male professions.

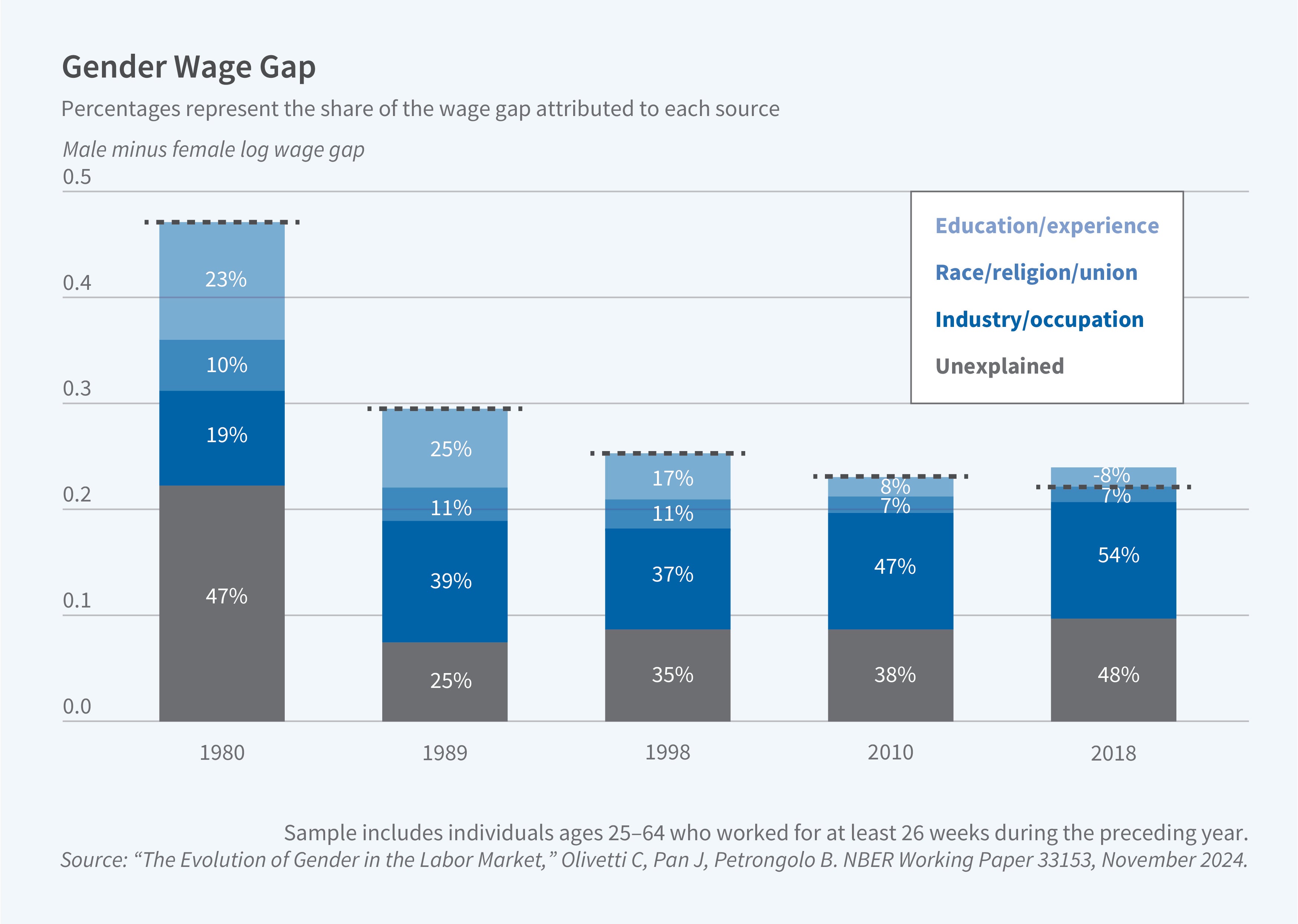

Despite decades of progress, sizable gender inequalities in employment and earnings remain. Pan, Petrongolo, and I analyze data from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics and find that as women have overtaken men in completed years of schooling and narrowed their gap in work experience relative to men, slightly more than half of the gender wage gap is now accounted for by the differential sorting of women and men into occupations and industries, with the remainder “unexplained” by observable characteristics.3 Structural issues within occupations and societal expectations, particularly regarding caregiving, are important for explaining the remaining gender gaps. Our analysis also proposes a simple model of labor supply to illustrate how unequal gender roles in the household and departures from competitive wage setting can shape earnings gaps even once gender productivity differentials (due to education, experience, or occupational choice) have vanished.

Evolving Perspectives

Over time, gender research has become mainstream, and there has been a clear shift from viewing women and men as single, representative agents to adopting a household-centric view where men and women take on dual roles in the labor market and the home. These roles are shaped by work-family trade-offs and cultural influences.

Why, despite this progress, do men and women still work different hours in the market and the home, sort into different jobs, and face different wage returns? There are two fundamentally different explanations for the existence of such gaps. One view is that men and women have inherently different preferences, skills, or psychological traits that drive their choices in education and careers. In this case, gender inequality is simply a manifestation of essential differences between men and women. The other view posits that men and women are similar in the relevant dimensions but face different opportunities and constraints. In this case, gender inequality can be a symptom of misallocation, and policies that promote gender equality can improve allocative efficiency. A key challenge in distinguishing between these views is that observed gender differences in skills, traits, or preferences can be affected by constraints in the form of norms, stereotypes, and discrimination.

Parenthood and Career Inequality

Women’s roles as child bearers and caregivers are significant hurdles to their continued participation in the workforce, particularly in highly paid but time-demanding careers. The consensus of past research on the trade-off between family and career for mothers and fathers holds that parenthood drives widening gender gaps in earnings and that, following the decline in productivity gaps and outright pay discrimination, the remaining gender gaps in developed countries are related to children.

Much of this extensive literature focuses on mothers. Mothers often reduce their work hours or leave the labor force altogether after having children, leading to slower career progression and a widening earnings gap. What happens when the kids grow up? What is the impact on fathers’ earnings relative to those of men who don’t have or will never have children?

In recent work, Claudia Goldin, Sari Kerr, and I use longitudinal data from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (1979), which tracks respondents from their twenties to their fifties, to analyze parenthood earnings dynamics as children age out of the parental household.4 We find that as children grow up and women work more hours, the motherhood penalty — that is, the earnings of mothers relative to those of non-mothers — is greatly reduced. The parental gender gap in earnings remains substantial, however, and is largely due to fathers benefiting from a “fatherhood premium” as societal norms reinforce their roles as primary earners.

Fathers earn a wage premium that cannot be fully explained by selection into fatherhood. That is, the tendency for higher-ability or harder-working men to be more likely to become fathers cannot explain the differential. This fatherhood premium is larger among college graduates and especially among men working in occupations that require long and/or inflexible hours. This evidence is consistent with progressive specialization of paid and unpaid work by men and women, respectively, once they become parents. Given the scant work in this area, investigating labor market and normative determinants of the fatherhood premium may be a promising area for further research.

Historical Patterns and Structural Shifts

In predominantly agricultural and less urban societies, most women work flexibly on or near household premises, making their work compatible with marriage and childcare. The transition to industrialization and the service economy, coupled with urbanization and the delocalization of work, drives progressively larger child-related gaps in employment. At the highest income levels, economies can create family-friendly jobs that make it easier to combine work and family life.

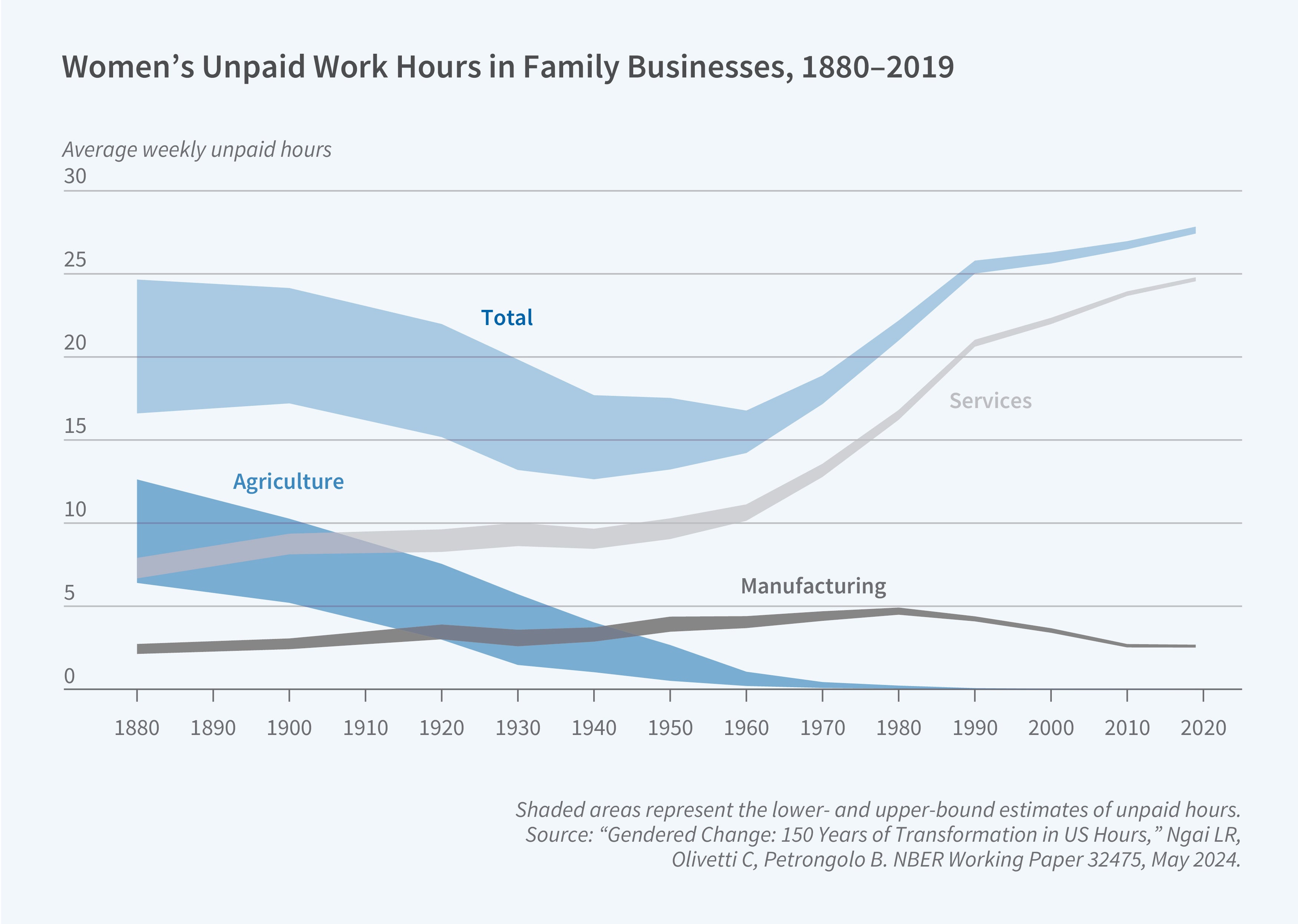

My recent work with Rachel Ngai and Petrongolo shows that this U-shaped pattern in women’s work is also found historically for the United States when we account for unpaid work on family farms.5 We construct a consistent measure of male and female work hours for the US over the period 1870–2019, encompassing extensive and intensive margins of labor supply. We emphasize the measurement of unpaid work in family businesses; this is hard to quantify pre-1940 when information on work hours was not recorded. For paid work hours and earnings by sector and gender, we use surveys commissioned by state Bureaus of Labor from the late 1880s to 1901, digitized by the Historical Labor Statistics Project at the University of California. For unpaid hours on family farms, we analyze early time-use studies conducted by the US Department of Agriculture and several state’s Agricultural Experiment Stations and other organizations between the mid-1920s and the mid-1950s. In addition to being critical for measuring women’s contributions to the economy, tracking unpaid work on family farms matters for the estimation of agricultural productivity and structural transformation.

We also examine the relationship between gender trends in work and economic development through the lens of two processes: structural transformation across agriculture, manufacturing, and services and the marketization of home production. During early development stages, declining agriculture leads to reallocation to services — both in the market and the home — and leisure, reducing market work for both genders. In later stages, structural transformation reallocates labor from manufacturing to services, while marketization reallocates labor from home to market services. Given gender specialization, male hours continue to decline while female hours increase.

We find that structural transformation and marketization can explain the decline in women’s work hours in the US before 1950. However, labor reallocation across sectors and marketization can only explain a quarter of the later changes, which were accompanied by other structural changes including the evolution of women’s aspirations and societal perceptions about appropriate gender roles in the household and the labor market.

The Role of Family Policies

The changing role of women in society generated government intervention and firm policies that often eased the struggles of families and, especially, new mothers. Albanesi, Petrongolo, and I recently reviewed evidence on the effect of these policies.6

Early legislation on parental leave rights mostly focused on protecting mothers’ health around birth and supporting child development, emphasizing — explicitly and implicitly — women’s traditional gender roles as wives and mothers in a male-breadwinner society. As more women entered the workforce in the latter half of the twentieth century, the demand for policies that balanced work and family life grew. Scandinavian countries led the charge with longer maternity leaves and quotas for fathers, while the US has been slower to adopt paid parental leave. Some states adopted such laws in recent years.

What lessons can be learned from decades of legislation and evaluations about the role of family policies for the new century? Studies of parental leave reforms in several European countries suggest that parental leave extensions typically delay mothers’ return to work after childbirth, with negative impacts on maternal earnings in the short run.

But there do not seem to be long-lasting effects — positive or negative — of parental leave on maternal earnings. Fathers’ quotas are a step toward encouraging shared parenting, but most fathers take only the bare minimum leave they are allotted. Funding for childcare consistently shows positive effects on women’s participation in the workforce across countries, especially when it replaces the need for mothers to provide childcare themselves.

Interestingly, the only example in US history of an (almost) universal, largely federally supported childcare program occurred during WWII under the Lanham Act, a federal infrastructure bill passed by Congress in 1940 and eventually used to fund programs for the preschool and school-aged children of working women. Joseph Ferrie, Goldin, and I find that these programs, though limited in scope, were more numerous in places with high female workforce participation, suggesting their effectiveness in supporting mothers working long hours in intensive employment.7

As gender inequality is increasingly tied to parenthood, women’s ability to reconcile work and family life remains crucial.

Endnotes

“The Evolution of Gender in the Labor Market,” Olivetti C, Pan J, Petrongolo B. NBER Working Paper 33153, November 2024.

“Families, Labor Markets, and Policy,” Albanesi S, Olivetti C, Petrongolo B. NBER Working Paper 30685, November 2022.

“The Evolution of Gender in the Labor Market,” Olivetti C, Pan J, Petrongolo B. NBER Working Paper 33153, November 2024.

“When the Kids Grow Up: Women’s Employment and Earnings across the Family Cycle,” Goldin C, Kerr SP, Olivetti C. NBER Working Paper 30323, August 2022.

“Gendered Change: 150 Years of Transformation in US Hours,” Ngai LR, Olivetti C, Petrongolo B. NBER Working Paper 32475, May 2024.

“Families, Labor Markets, and Policy,” Albanesi S, Olivetti C, Petrongolo B. NBER Working Paper 30685, November 2022.

“Mobilizing the Manpower of Mothers: Childcare under the Lanham Act during WWII,” Ferrie JP, Goldin C, Olivetti C. NBER Working Paper 32755, July 2024.