The Economics of Transformative AI

The rapid advancement of artificial intelligence (AI) may usher in the most significant economic transformation since the Industrial Revolution. For nearly a decade, as I witnessed the continuous progress in deep learning, I have been studying the economics of transformative AI — how our economy may be transformed as AI systems advance toward mastering all forms of cognitive work that can be performed by humans, including new tasks that don’t even exist yet. The prospect of understanding the strange new world we will inhabit when transformative AI is developed has felt both intellectually urgent and personally meaningful to me as a father of two young children.

Today, AI systems are approaching and exceeding human-level performance in many domains, and it looks increasingly like our world will be transformed before my children have grown up. In this research summary, I outline my analysis of how transformative AI could reshape our economy, discuss frameworks for preparing for this transition, and explore how AI tools are already transforming economic research itself.

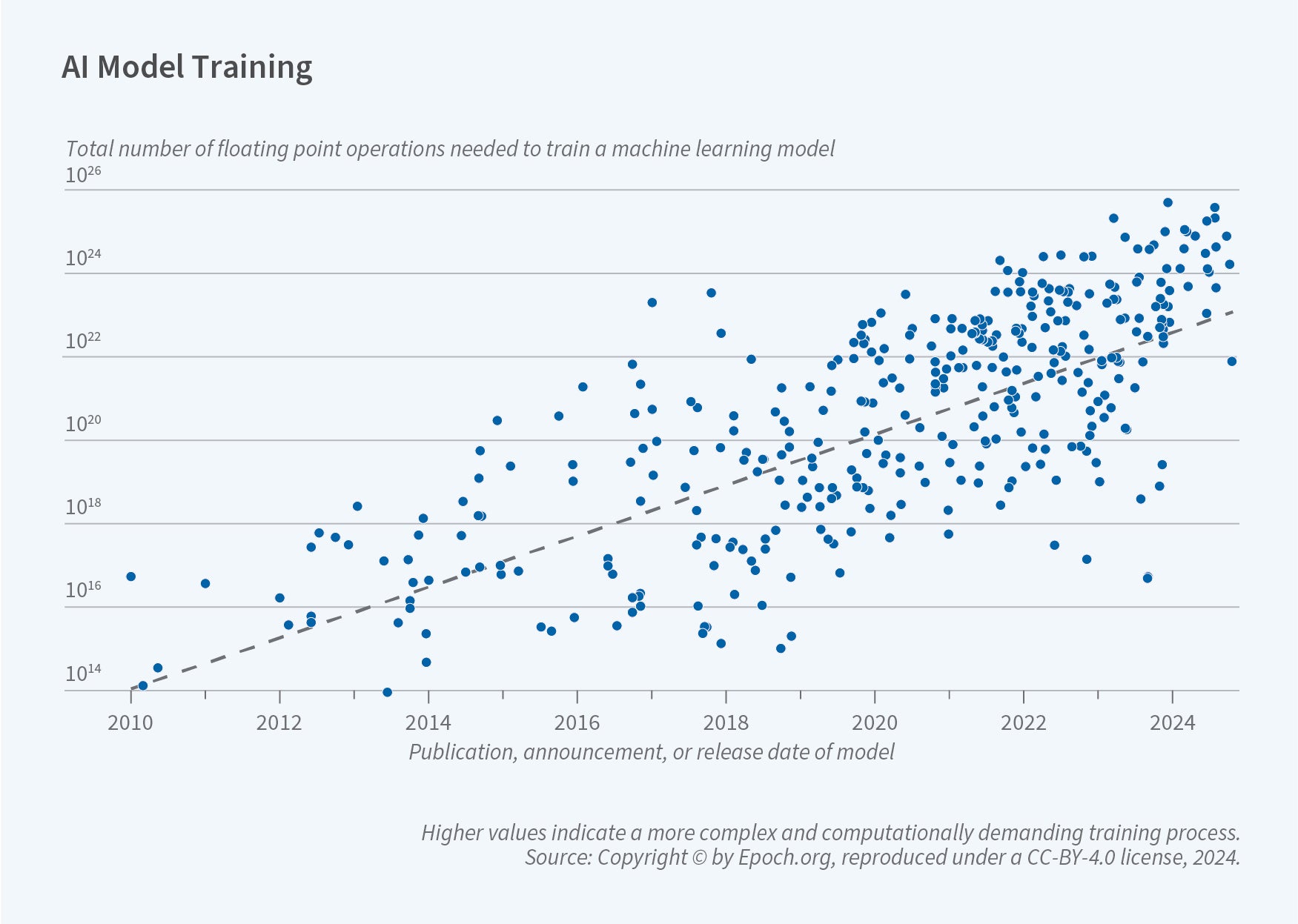

The pace of advancement in AI has been nothing short of extraordinary. Over the past 15 years, the computational resources employed to train cutting-edge AI systems have grown by a factor of four every year, as illustrated in Figure 1. The costs of such training are currently in the realm of hundreds of millions of dollars, as described in a market structure analysis with Jai Vipra.1 This exponential growth in compute has been accompanied by significant improvements in algorithmic efficiency, which Epoch AI estimates to be occurring at a rate of two and a half times per year. Taken together, these advances imply increases in the effective compute of frontier AI systems of 10 times per year. So-called scaling laws describe how the rapid growth in inputs translates into AI’s performance gains, providing AI labs and their investors with some predictability for the returns on their investments and facilitating their bets on the next billion-dollar training runs. While returns to additional computing power may eventually diminish in some domains due to data scarcity, there are compelling reasons to expect that scaling will continue to yield significant capability gains in the coming years.

A growing number of leading AI researchers and industry figures now predict transformative AI could arrive within years, not decades. Geoffrey Hinton, the 2024 Nobel laureate in physics, considers it a possibility before the decade’s end. Sam Altman of OpenAI anticipates superintelligence “within a few thousand days,” while Anthropic’s CEO Dario Amodei expects transformative AI by 2027, if not sooner. While these experts — and critics who view recent AI advances as overhyped — acknowledge the profound uncertainty in such predictions, the potential consequences of transformative AI are so significant that I consider it crucial for economists to analyze them.

Given the rapid pace of advancement of AI, my research agenda focuses on two critical areas: (1) analyzing transformative AI’s economic implications, and (2) leveraging AI to enhance economic research and increase our research productivity.

In the context of (1), I have recently laid out a research agenda for the economics of transformative AI together with Ajay Agrawal and Erik Brynjolfsson.2 The agenda poses what we view as key economic questions to help us better prepare for the age of transformative AI. They cover economic growth, innovation, income distribution, decision-making power, geopolitics, information flows, AI safety, and human wellbeing under AI.

A New Economic Paradigm

To analyze the economic implications of transformative AI, it is instructive to examine how past technological revolutions have reshaped the structure of our economy. The transition from the Malthusian to the Industrial Age is particularly relevant for the changes and challenges that may lie ahead, as I explain in a recent paper.3

In the Malthusian Age, land was the critical bottleneck factor, while human labor could be considered reproducible on the relevant time scales. As technology was largely stagnant, the available supply of land limited the size of the human population it could support. In this era, land was the most valuable economic resource. Human labor, in contrast, was not particularly valuable.

The Industrial Age — the world we still inhabit — transformed this reality. Rapid technological progress became a key driver of growth, accompanied by reproducible capital in the form of machines and factories, as captured by the standard neoclassical production function. With technology advancing and capital accumulating, labor suddenly became the bottleneck. This scarcity of labor led to large increases in wages, giving rise to today’s living standards, which have grown about twentyfold in advanced economies since the Industrial Revolution.

Transformative AI could usher in another paradigm shift by making human-level intelligence reproducible. AI systems and robots could eventually substitute for both cognitive and physical human labor. In this new age, both traditional capital and intelligent machines would be reproducible resources, with the distinction between them increasingly blurred. These factors could be accumulated without bounds and generate ever more economic capacity.4

The implications are profound. Growth would accelerate as capital accumulates and artificial brainpower drives innovation. However, labor would lose its special status, and therefore the main bottleneck of the Industrial Age would be surmounted.

Understanding these changes requires careful analysis of how relative prices will evolve. While many noneconomists predict that transformative AI will dramatically reduce all prices, relative prices are what matter economically. For instance, the relative prices of computers, robots, and human labor may decline while those of energy, food, and housing may rise. Systematic analysis must distinguish between reproducible factors — like compute and robots — and irreproducible ones that may become relatively more valuable, such as land, raw materials, and perhaps energy. This may fundamentally challenge our present system of income distribution.

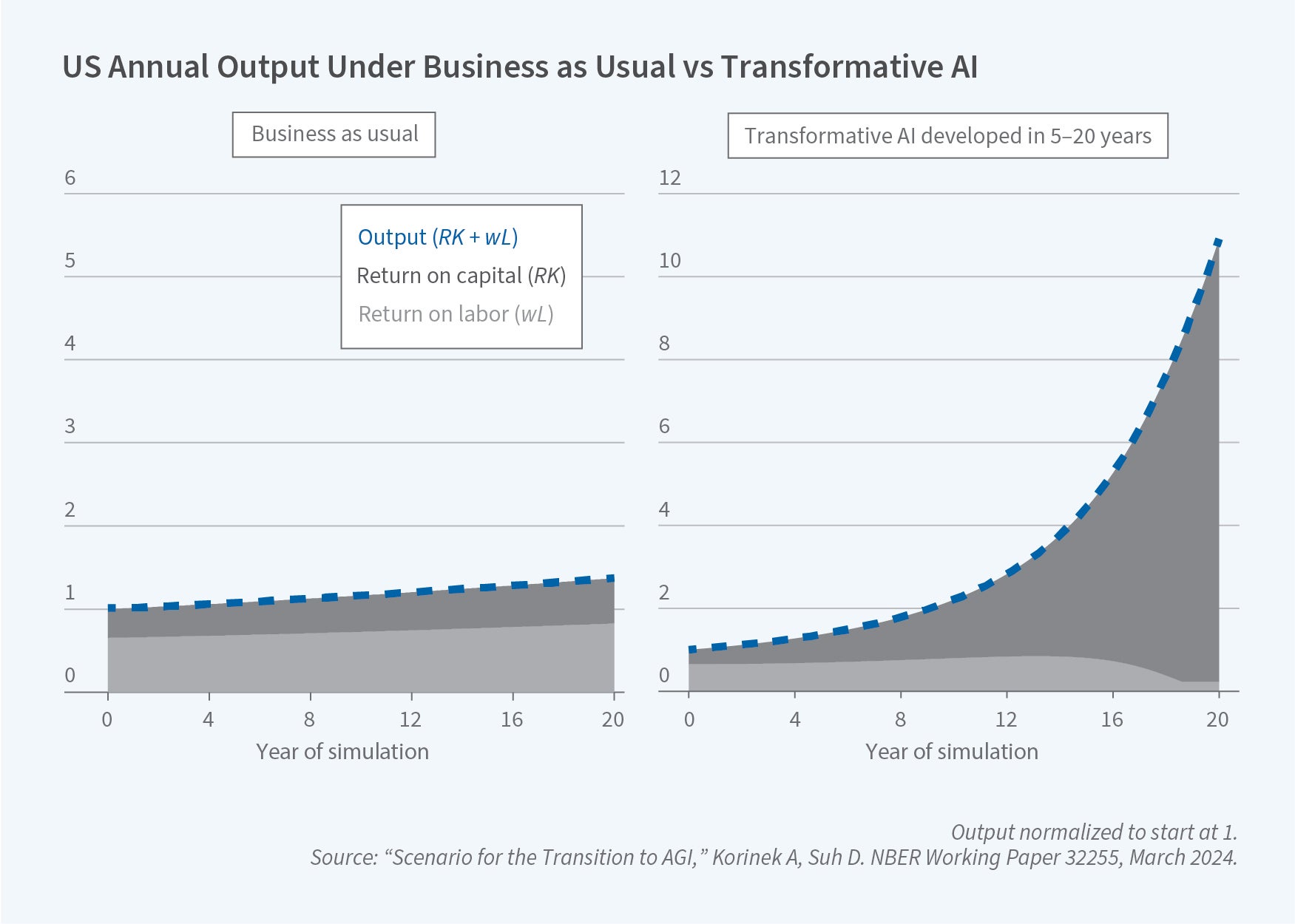

Given the profound uncertainty about the trajectory and timeline of AI progression, I have developed a systematic scenario planning approach. In recent work, Donghyun Suh and I compared a “business as usual” scenario where AI automates tasks gradually as in past decades with two scenarios where transformative AI emerges in either 5 or 20 years.5 For each scenario, we model how automation and capital accumulation interact to determine economic outcomes. The various scenarios produce starkly different trajectories — from steady growth with rising wages in the business-as-usual case to more than tenfold output expansion but collapsing wages in the transformative AI scenarios, as illustrated in Figure 2.

This scenario-based framework provides a structured way for policymakers and business leaders to stress test existing institutions and develop contingency plans for possible futures. Rather than betting everything on a single prediction, it allows us to identify robust strategies that work reasonably well across scenarios while maintaining the flexibility to adapt as the future unfolds. The stark differences between scenarios also highlight the importance of considering the labor market challenges that may emerge.6

Labor Market Challenges

Labor serves three vital functions in our modern economy: it acts as the key bottleneck factor in production, provides the main source of income for most people, and constitutes the primary use of time for working-age individuals. If transformative AI and advanced robots can substitute for human cognitive and physical capabilities, it threatens to fundamentally disrupt all three functions.7

As a first approximation, if AI becomes a substitute for human labor, it will eliminate labor’s role as a bottleneck factor in production. Just as the Industrial Revolution ended the Malthusian era, transformative AI could end the Industrial Era by making labor reproducible. This would likely lead to significant devaluation of human labor as machines become progressively cheaper and more capable. As I observe in a paper with Joseph Stiglitz, it also calls for discussion of potential systems of income distribution that are independent of labor market earnings.8 Moreover, these economic challenges could pose significant risks to democratic stability, as rising inequality may trigger a vicious cycle of eroding democracy and further increasing inequality.9

However, as we transition to such a state, there are also opportunities to actively steer the direction of technological progress. In other joint work with Stiglitz, we develop a theoretical framework for identifying and promoting innovations that increase labor demand and create better-paying jobs as a second-best measure to obtain a desirable distribution of income.10 Examples of such innovations include intelligent assistants that enhance worker productivity rather than replace workers entirely. The framework analyzes how different innovations affect labor demand and factor shares through their technological complementarity to workers and their impacts on relative incomes. Building on this, my work with Katya Klinova proposes practical guidelines for AI developers to evaluate the labor market impacts of their innovations, providing them with a framework to advance shared prosperity rather than exacerbate inequality.11

The decline of work as society’s primary use of time raises important questions about whether humans need work beyond its economic value. Economic analysis suggests that if the meaning people derive from work is purely a private good, like most other work amenities, there is no inherent reason for policy intervention — those who gain sufficient personal value can continue working even at low or zero wages. However, if work generates positive externalities, for example, through social connections and political stability, or if individuals systematically undervalue work’s benefits due to internalities, there may be a role for policy to encourage work participation. That said, as autonomous machines become more capable, it may be more efficient to develop alternative institutions that provide these social benefits without requiring humans to work.

The AI transformation also challenges the traditional value proposition of education and human capital development, which has historically served as society’s primary mechanism for economic advancement. A fundamental reevaluation of education’s role and purpose will be necessary in a world where cognitive skills are increasingly automatable.12

The challenges of managing transformative AI’s distributive effects become even more complex in our globalized economy. As I detailed in a third paper with Stiglitz, while domestic policy measures can potentially compensate losers within countries, there are no effective mechanisms for cross-border compensation if technological progress deteriorates the terms of trade of entire nations.13 Transformative AI may exacerbate these challenges by concentrating economic power in a few increasingly advanced economies. The capital- and knowledge-intensive nature of AI development may make it harder for developing countries to keep up. Without international action to ensure an equitable distribution of AI’s benefits, there is a risk of reversing decades of progress in global development.

Advancing Economic Research with AI

Having outlined these critical challenges facing our economy, let me return to the second prong of my research agenda: exploring how we can leverage AI to enhance economic research. The ongoing advances in generative AI are creating opportunities to revolutionize how we conduct economic research, making economists more productive and better equipped to address the complex challenges discussed above. My work explores both the practical applications of these technologies and their broader implications for the economics profession.

In a recent paper and on the dedicated website genaiforecon.org, I demonstrate with tangible examples how large language models (LLMs) can serve as powerful research assistants across the entire research workflow.14 LLMs can help with ideation and brainstorming, providing fresh perspectives and counterarguments to evaluate and strengthen analyses. They excel at writing tasks, from drafting and editing to generating engaging summaries for different audiences. In background research, they can process and synthesize vast amounts of information, making literature reviews more comprehensive and efficient. For data analysis, they can extract information from text, classify content, and even simulate human subjects. They are particularly capable at coding tasks and can increasingly assist with mathematical derivations.

In a November 2024 paper, I describe the latest advances in generative AI that are useful for researchers.15 These include improved math and reasoning capabilities, real-time search, and more sophisticated collaboration tools that are changing how we can interact with these systems. New LLM-powered workspaces allow for dynamic, iterative collaboration between researchers and AI assistants. Moreover, the introduction of real-time voice interfaces and autonomous computer-use capabilities is making these interactions more natural and powerful.

These developments suggest a future where the role of economists will evolve significantly. In the short to medium term, we may focus more on our comparative advantages, such as posing questions, suggesting research directions, discriminating between useful and irrelevant content, and coordinating complex research projects. The basic and mundane aspects of research may be increasingly automated, allowing economists to focus on higher-level thinking and creative problem-solving.

A research agenda emerges from these observations. We need to develop frameworks for evaluating AI-augmented research output as the bottleneck shifts from generation to assessment. We should investigate how to best integrate AI tools into our research workflows while maintaining rigorous standards and avoiding potential pitfalls like the homogenization of research approaches. We must also consider how to optimally time research projects given the rapid pace of AI advancement; some inquiries might be optimally postponed until more powerful tools are available.

Looking further ahead, when transformative AI is reached, it will surpass human capabilities in generating and articulating economic insights. As with all human labor, this possibility also raises profound questions about the future of the economics profession.

It may well be that we have only a handful of research projects left before our ability to write insightful economics papers is outpaced by machines that surpass our intellectual capabilities. This increases the stakes and makes it important to carefully choose the most impactful work to pursue. I believe that one of the highest-value research priorities is to help ensure that increasingly powerful AI systems are developed and deployed in our economies in ways that are aligned with human values. As economists, we are uniquely positioned to translate concepts from the social sciences into analytic frameworks that can guide the development of aligned AI systems, making this an urgent and worthy focus.16

Endnotes

“Concentrating Intelligence: Scaling and Market Structure in Artificial Intelligence,” Korinek A, Vipra J. NBER Working Paper 33139, November 2024, and forthcoming in Economic Policy, January 2025.

“A Research Agenda for the Economics of Transformative AI,” Brynjolfsson E, Korinek A, Agrawal A. Stanford Digital Economy Lab Working Paper, November 2024.

“Economic Policy Challenges for the Age of AI,” Korinek A. NBER Working Paper 32980, September 2024.

“Economic Growth under Transformative AI,” Trammell P, Korinek A. NBER Working Paper 31815, October 2023.

“Scenario Planning for an A(G)I Future,” Korinek A. IMF Finance & Development Magazine 60(4), December 2023, pp. 30–33.

“Preparing for the (Non-Existent?) Future of Work,” Korinek A, Juelfs M. NBER Working Paper 30172, June 2022, and The Oxford Handbook of AI Governance, Bullock J, Chen YC, Himmelreich J, Hudson V, Korinek A, Young MM, Zhang B, editors, pp. 746–776. New York: Oxford University Press, 2024.

“Artificial Intelligence and Its Implications for Income Distribution and Unemployment,” Korinek A, Stiglitz JE. NBER Working Paper 24174, January 2018, and The Economics of Artificial Intelligence: An Agenda, Agrawal A, Gans J, Goldfarb A, editors. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2019.

“AI’s Economic Peril,” Bell SA, Korinek A. Journal of Democracy 34(4), October 2023, pp. 151–161.

“Steering Technological Progress,” Korinek A, Stiglitz JE. Paper presented at the NBER Economics of Artificial Intelligence conference, September 24–25, 2020.

“AI and Shared Prosperity,” Klinova K, Korinek A. Proceedings of the 2021 AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society (AIES ’21), July 2021, pp. 645–651.

“Economic Policy Challenges for the Age of AI,” Korinek A. NBER Working Paper 32980, September 2024.

“Artificial Intelligence, Globalization, and Strategies for Economic Development,” Korinek A, Stiglitz JE. NBER Working Paper 28453, February 2021.

“Language Models and Cognitive Automation for Economic Research,” Korinek A. NBER Working Paper 30957, February 2023. Published as “Generative AI for Economic Research: Use Cases and Implications for Economists” in the Journal of Economic Literature 61(4), December 2023, pp. 1281–1317.

“Generative AI for Economic Research: LLMs Learn to Collaborate and Reason,” Korinek A. NBER Working Paper 33198, November 2024, and update of “Generative AI for Economic Research: Use Cases and Implications for Economists,” Journal of Economic Literature 61(4), December 2023, pp. 1281–1317.

“Aligned with Whom? Direct and Social Goals for AI Systems,” Korinek A, Balwit A. NBER Working Paper 30017, May 2022, and The Oxford Handbook of AI Governance, Bullock J, Chen YC, Himmelreich J, Hudson V, Korinek A, Young MM, Zhang B, editors, 65–85. New York: Oxford University Press, 2024.