Understanding Early Childhood Development and Its Importance

In the process of human development, what happens in the early years — including the first thousand days after conception — is of key importance for determining life-cycle outcomes. Early outcomes, however, are not fixed at birth or determined exclusively by genetics; they are influenced by a variety of factors, including parental behaviors, the environments children live in, and policy interventions. Furthermore, human development is a multidimensional process, with different skills leading to different adult outcomes by interacting in complex ways during the developmental process. Such multidimensionality is made salient by the important roles that different skills play in the production process.

These areas of general consensus are the result of years of contributions by a wide range of researchers to a large, growing, and diverse literature, which I cannot summarize satisfactorily here. I review selected papers from earlier work and my recent research to discuss where the literature stands, with an emphasis on what I think are open challenges and questions for future investigation.

Longitudinal Studies and Long-Run Evidence

Evidence on the importance of the early years and their malleability has been accumulating for decades from both developed and developing countries in a growing literature too large to cite here. In developed countries, several studies have shown the impact of various dimensions of early health status on adult outcomes, including in-womb experience, birth weight, and nutritional status in the early years. Similar evidence is available from developing countries. The widely used Consortium of Health-Orientated Research in Transitioning Societies (COHORTS) studies, for instance, were developed in Brazil, Guatemala, India, the Philippines, and South Africa, while the Young Lives project is still collecting information on two cohorts of children born in Ethiopia, India, Peru, and Vietnam as they age through their 20s. The Guatemalan COHORTS study, run by the Institute of Nutrition of Central America and Panama (INCAP), has been following children for about 50 years (and counting), finding that early-life nutritional status impacts multiple health, cognitive, and socioeconomic outcomes of adults decades later.

Much of the available evidence refers to the effects of children’s health and nutritional status on adult outcomes. By contrast, evidence on the impacts of early cognitive or socioemotional skills on late childhood and adult development is much scarcer, partly because of the limited availability of longitudinal data, including limited early-year information on different dimensions of child development.

Some of my recent research seeks to help address these gaps. My recent paper with Darwin Cortes, Dario Maldonado, Paul Rodriguez-Lesmes, Natalie Charpak, Rejean Tessier, Juan G. Ruiz, Juan Gallego, Tiberio Hernandez, Felipe Uriza, and Andres Gallegos uses data from the 20-year follow-up evaluation of kangaroo mother care (KMC).1 KMC is a relatively short intervention at the start of life — often defined as skin-to-skin contact between mother and newborn, frequent or exclusive breastfeeding, and early discharge from the hospital — often targeted to underweight and premature babies. Analyzing data from an experimental KMC intervention in Colombia that began in 1993–94, we find that certain skills measured at 12 months are predictive of outcomes 20 years later, including cognitive and socioemotional skills. Furthermore, KMC has an impact on adult socioemotional skills and involvement in violent episodes. Our findings suggest that these impacts are mediated by the greater attachment that parents exhibit during the first year of life.

Policy Interventions and Their Impacts

For some time, the prevalent view was that skills like intelligence were mostly inherited and determined at birth — a view that only began to be questioned in the 1930s, as described in the wonderful book by Marilyn Brookwood.2 More recently, a wealth of rigorous evidence has shown that early development can indeed be affected by policy interventions.

Much of this literature comes from developed countries. Several prominent interventions, such as Michigan’s Perry Preschool Project, North Carolina’s Abecedarian, Tennessee’s Nurse-Family Partnership, the Chicago Child-Parent Center Program, and the Irish Learning for Life program have been shown to have long-term impacts.3 Some programs go beyond small randomized controlled trials (RCT) and have been rolled out (and to an extent evaluated) on a large scale in the US (i.e., Head Start) and the UK (i.e., Sure Start), with the available evidence suggesting that they have large benefits, particularly for the most disadvantaged children.

Some interesting evidence on the impact of early-years interventions also comes from developing countries. In Colombia, for instance, studies of early-year stimulation interventions showed sizeable impacts as early as the 1970s4 and later.5 The best-known evidence, however, is from what is now known as Reach Up and Learn (RULe), an early-years cognitive/socioemotional intervention in Jamaica6 that has followed the original trial’s subjects for decades, enabling researchers to study its remarkable long-run effects on various adult outcomes.7 Partly because of its success, the RULe intervention has been replicated and adapted to multiple contexts and countries.8

Three of my recent papers have studied the effects of RULe replications. In Colombia, work with Sarah Cattan, Emla Fitzsimons, Costas Meghir, and Marta Rubio-Codina argued that the significant gains in cognitive and socioemotional skills observed in a RULe RCT targeted at disadvantaged children aged 12 to 24 months were mediated by increases in parental investments.9 In China, work with Sean Sylvia, Nele Warrinnier, Renfu Luo, Ai Yue, Alexis Medina, and Scott Rozelle found that a home-based parenting program delivered by the Family Planning Commission significantly increased infant skill development after six months.10 (An application by other researchers explicitly compares a similar program in China with the original Jamaican trial.11) And in rural India, my work with Meghir, Pamela Jervis, Monimalika Day, Prerna Makkar, Jere Behrman, Prachi Gupta, Rashim Pal, Angus Phimister, Nisha Vernekar, and Sally Grantham-McGregor found that an early-years stimulation intervention had positive impacts on both IQ and school readiness and that these effects were sustained after 15 months.12 As with other adaptations of RULe, the India trial explored different modes of delivery — including home visits, as in the original Jamaican intervention, and group visits. They all had similar average impacts, likely through different mechanisms.

My research has also focused on the medium-run impacts of early cognitive/socioemotional interventions, though the findings have been more mixed. In the Colombian intervention mentioned above, for example, work with Alison Andrew, Fitzsimons, Grantham-McGregor, Meghir, and Rubio-Codina found that the initial impacts waned two years after it ended.13

In other contexts, however, the results are different. The aforementioned study from India, for example, found sizeable positive medium-run impacts for that RULe intervention.14 Similarly, recent work with Jervis, Lina Cardona-Sosa, Michele Giannola, Grantham-McGregor, Meghir, Day, and Rubio-Codina looks at the medium-run effects of a RULe intervention in urban India and finds sizeable impacts on school readiness almost four years after the intervention’s completion.15 In Bangladesh, a recent paper finds positive impacts six years after the initial intervention, with larger impacts on children with anemia.16 This mixed evidence indicates that many factors might be at play, ranging from the quality of the intervention — and its success in changing parental behaviors on a sustainable basis — to the interaction of the initial effects with different environments that children face. To explain these different impacts, it is key to understand the mechanisms behind them.

While this research emphasizes the large potential impacts of interventions in the early years of life, it is important to note that policies directed at older children and adolescents are also useful.

The Drivers of Child Development

My research and this very partial summary of the literature make clear that the early years and their malleability are critically important. However, there are still important gaps in our understanding of the child development process and its many dimensions that make the design of effective policies difficult. For example, we do not fully understand how the development process changes as children age, nor what factors could or should be targeted by interventions that, when implemented at scale, might have to rely on limited financial and human resources. As previous studies have stressed,17 child development is a complex process, with different skills interacting contemporaneously and dynamically. The relative paucity of data, especially for the early years, has limited what we know: better and richer longitudinal data providing information on various aspects of development at different ages is needed. Such data, if linked to specific intervention evaluations, could enable precise impact estimates while also providing a better understanding of the mechanisms behind human development.

The Complex Process of Child Development

Recent work with Raquel Bernal, Giannola, and Milagros Nores uses a dataset from Colombia that follows a sample of (relatively disadvantaged) children from ages 1 to 7, with yearly observations.18 This relatively high frequency of data collection allows us to study the skill-formation process on a year-by-year basis and document how it changes over time. We consider three key dimensions (cognition, socioemotional skills, and health) and describe how their distribution evolves with age.

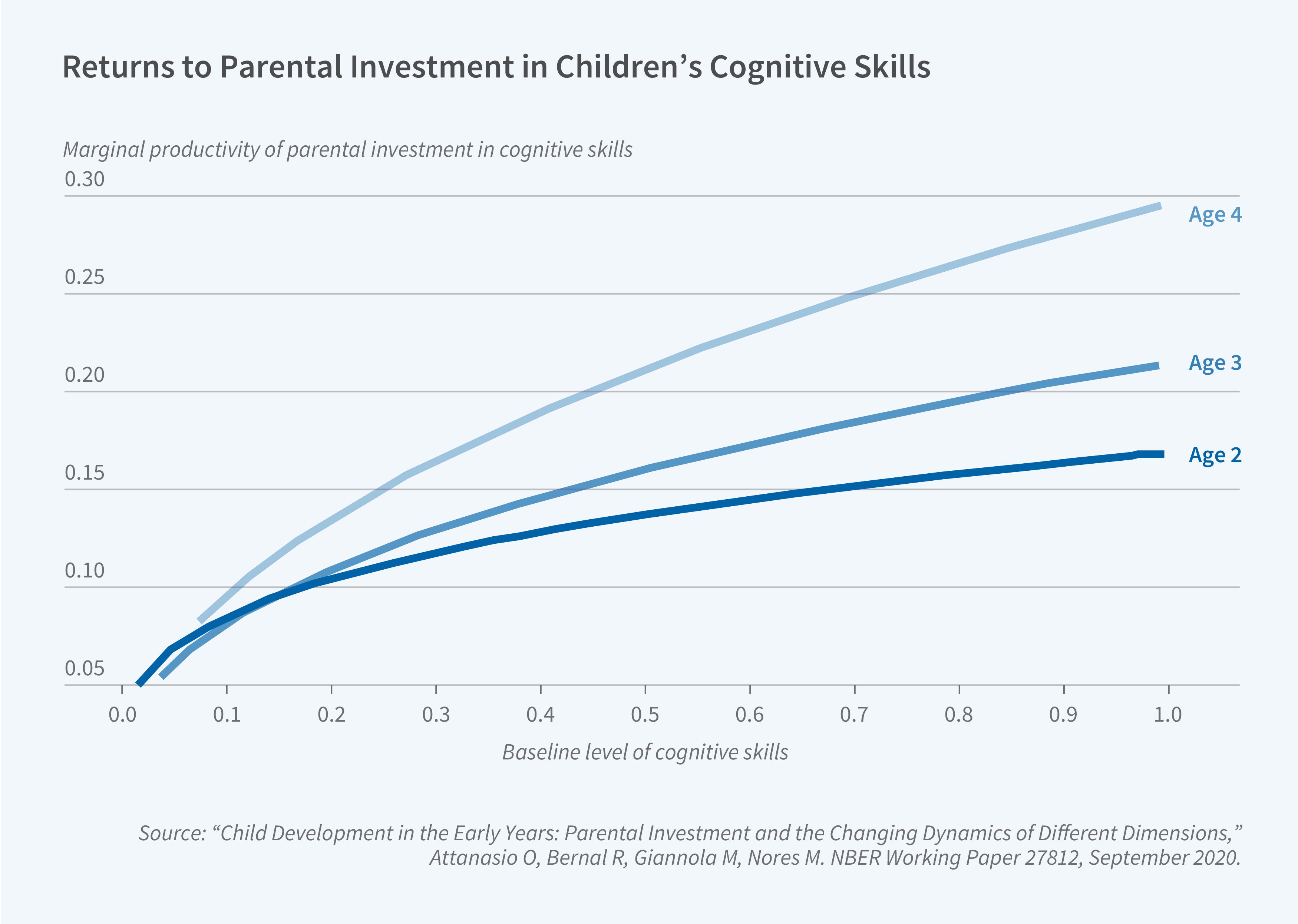

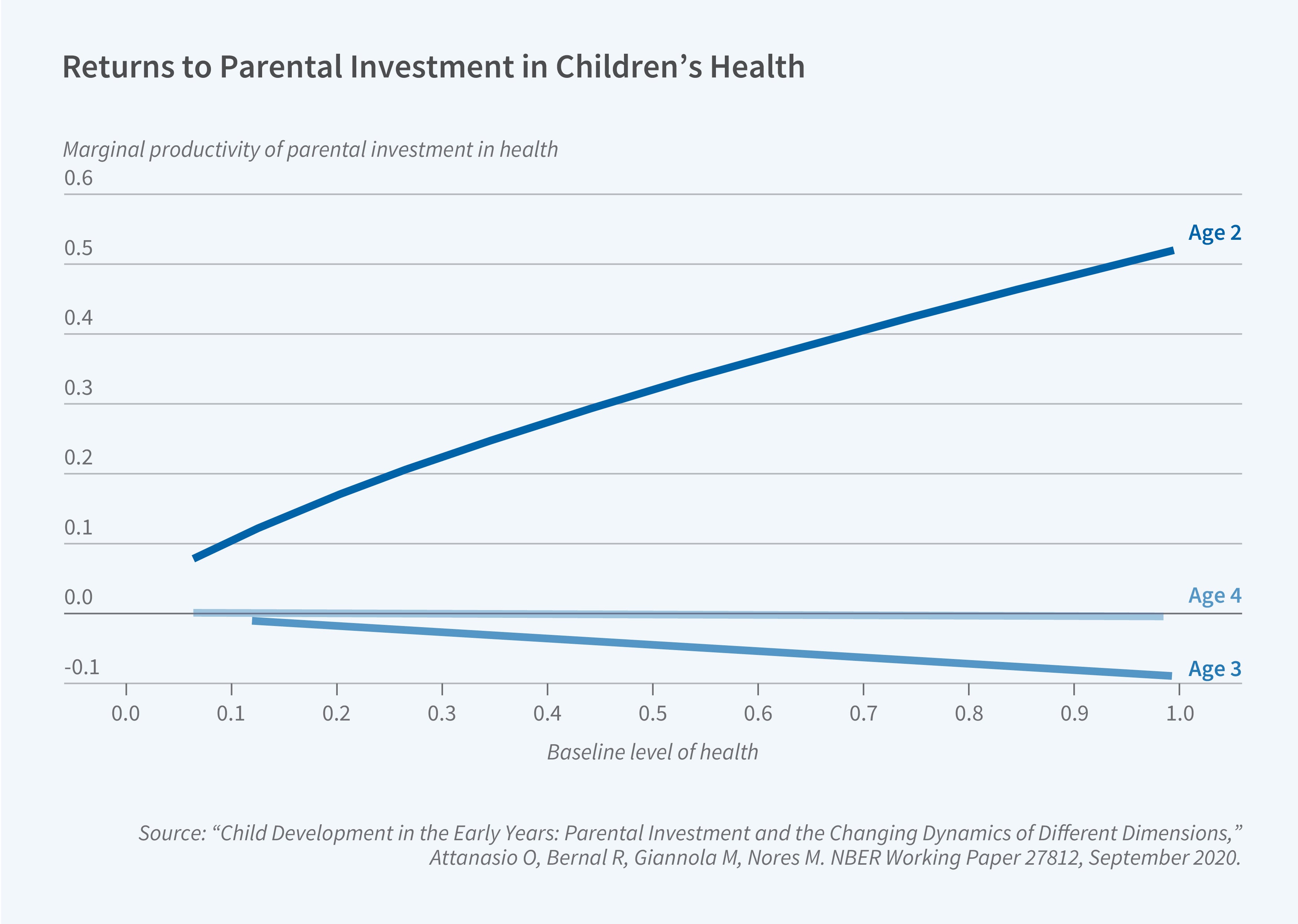

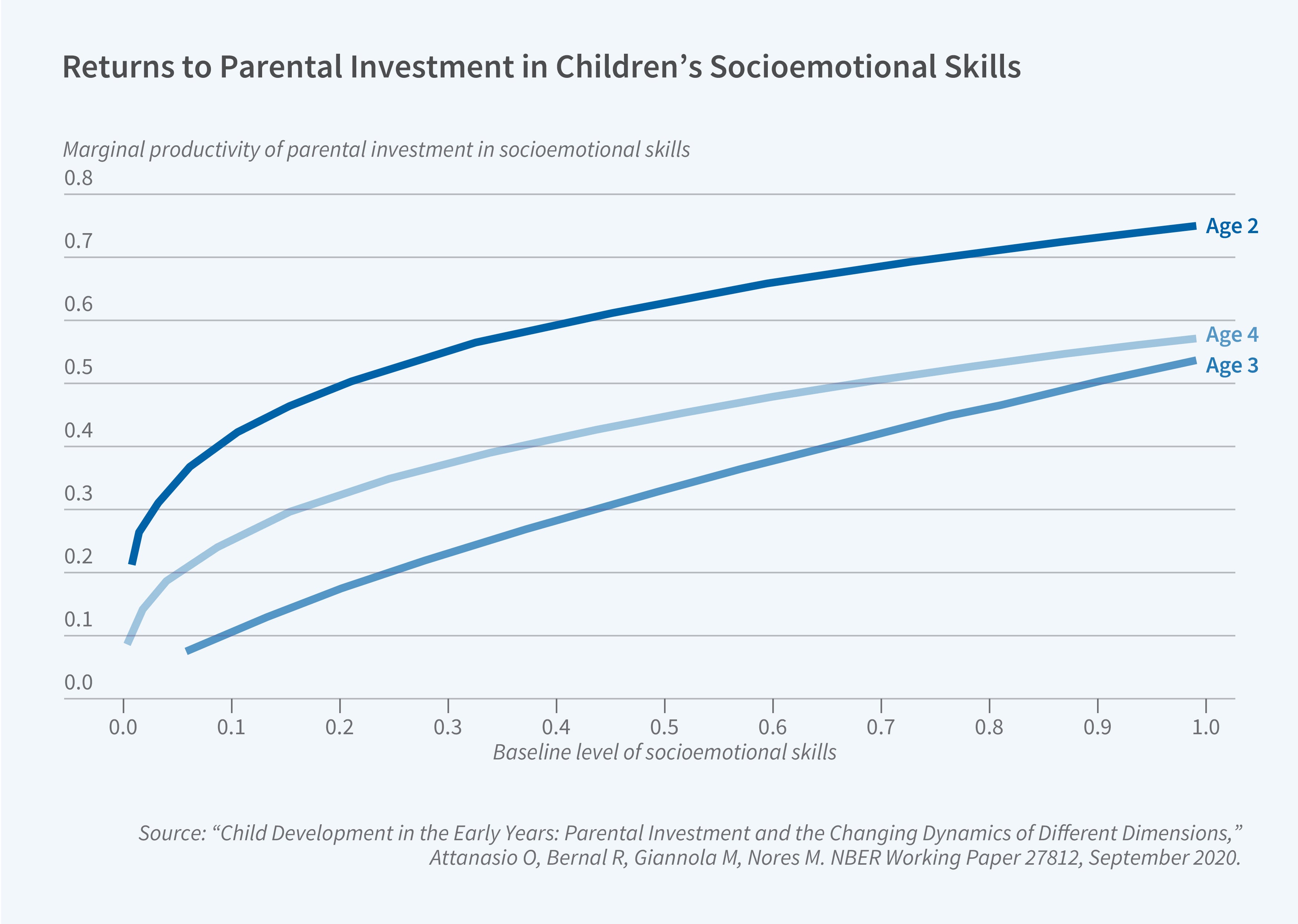

We have several findings. First, in some dimensions and for some ages, the dynamics of the process are complex, with multiple developmental lags being relevant. Second, to assess the productivity of parental investments, it is important to consider the fact that parental behavior is a choice. Third, child development processes — and the productivity of parental investments on the dimensions we consider — change considerably with age. Cognition, for instance, becomes progressively more persistent, particularly after age 4. The productivity of early-years parental investments is particularly high for cognition, while later parental investments are important for socioemotional skills. Figure 2 illustrates how the productivity of parental investments varies, both by age and by initial conditions.

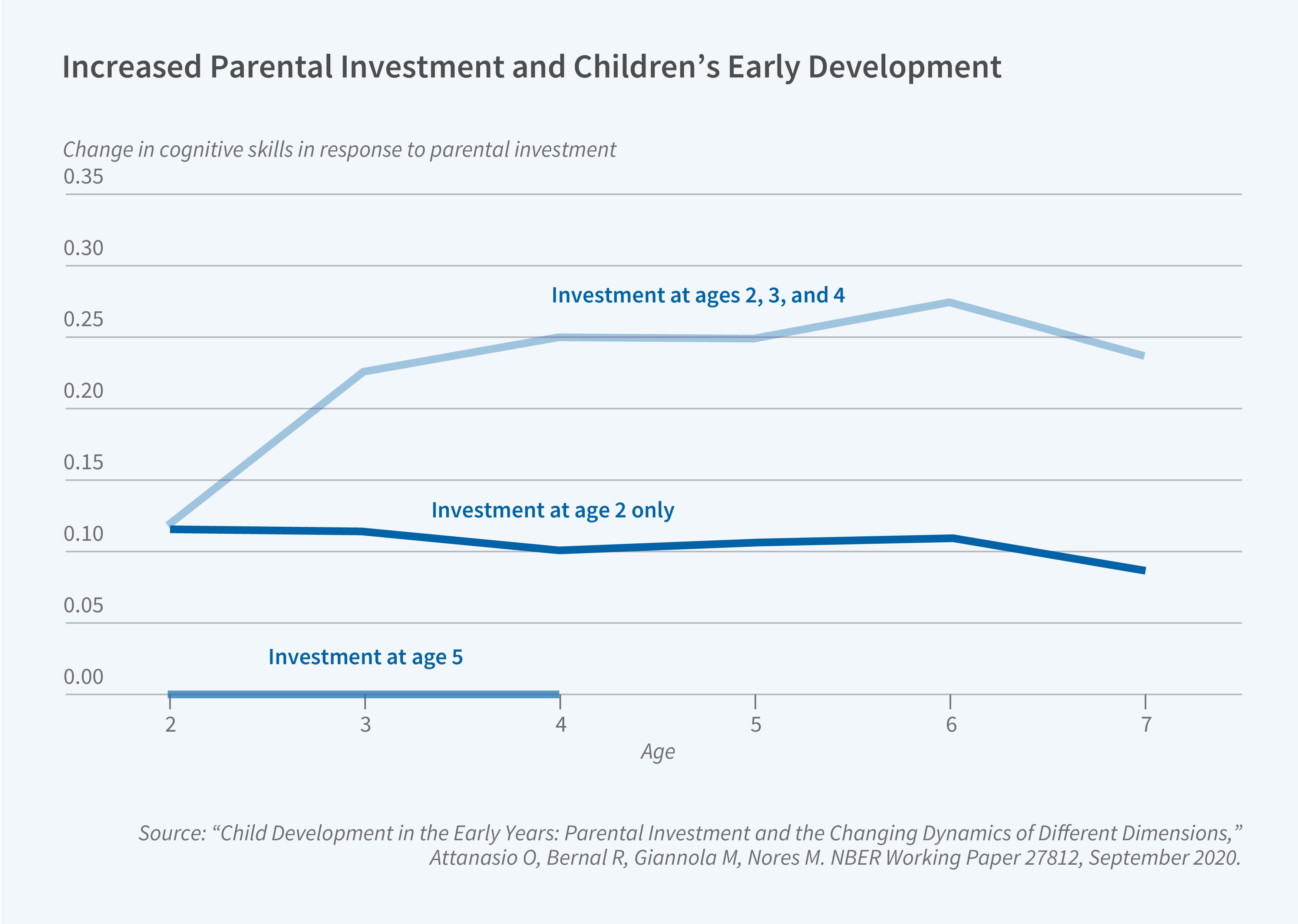

Figure 3 illustrates how exogenous increases in parental investments at different ages affect cognitive development in various ways. This highlights that understanding the complex dynamics of child development is not only an academic exercise; grasping how different inputs and their effects change with age is crucial for designing and implementing effective, scalable policies.

Parental Behavior, Social Norms

Parents clearly play key roles in shaping the early years of development. But what drives parental behaviors? Simple models point to some of the key drivers, including parents’ tastes, resources, and perceptions of the child development process. If parents do not spend much time stimulating their children, it may be because they underestimate the usefulness of such activities — an explanation that is consistent with the anthropological and sociological evidence.19

Flávio Cunha, Jervis, and I provide quantitative evidence on the role of parental beliefs using data from Colombia collected as part of the RULe evaluation mentioned earlier.20 We elicit parental beliefs about the returns to parental investments in child development and compare those subjective beliefs to objective data. Parents in the sample systematically underestimate the productivity of parental investment. This is clearly visible when it is assumed the productivity of parental investment does not depend on the initial level of child development. If investment productivity changes with initial conditions, we again find that parents underestimate productivity, particularly at high levels of initial conditions. Similar research has been conducted using data from Guatemala21 and the US22 while another recent paper23 explores how residential sorting can result in distorted beliefs about child development.

In addition to subjective beliefs about child development, other factors are likely important for determining parental behavior and the inputs children receive. Ingvild Almås, Jervis, and I have analyzed the dynamics within families and found that the relative position of husbands and wives might be relevant for determining parenting choices.24 Poor families might also have to allocate limited resources among several children.25 Likewise, gender and other social norms absorbed during the early years might be key, as recently shown using the British 1958 birth cohort.26

Childcare, Preschool Centers, Primary Schools

Parental inputs in the first years of life are not the only factors affecting individual development. My research also looks at inputs children start receiving as they age, including from childcare centers, preschool teachers, and peers. In work with Ricardo Paes de Barros, Pedro Carneiro, David K. Evans, Lycia Lima, Pedro Olinto, and Norbert Schady, I look at the impact of Brazilian childcare centers on children aged 0 to 3 as well as on their parents or caregivers. With data from Rio de Janeiro following an opt-in lottery program, we show that the average time in daycare for the city’s children increased by 34 percent during the first four years of life — giving parents and caregivers more time to work, resulting in higher incomes for beneficiary households.27 Beneficiary children saw sustained gains in height-for-age and weight-for-age (likely due to the better nutritional intake in daycare) as well as shorter-term gains in cognitive development. We also find that childcare-center quality is likely to interact with the quality of early-years inputs that children receive at home: the cognitive benefits, for example, were primarily driven by short-term improvements in home resources and environments due to increased household incomes.

Recent research also suggests that the ways in which different interventions affect the quantity and quality of childcare centers and preschools can be extremely important. In work with Andrew, Bernal, Cardona-Sosa, Sonya Krutikova, and Rubio-Codina, I evaluate two strategies to improve the quality of public preschools in Colombia: providing extra funding, mainly earmarked for hiring teaching assistants, and offering low-cost training for existing teachers.28 The first intervention had no effect on child development, largely because it reduced the time that existing teachers focused on teaching. The second intervention, however, improved children’s cognitive development, especially for more disadvantaged children. Similar research on preschool quality has used data from Ghana29 and Mexico30 while other studies have focused on primary schools in a variety of countries. Later-childhood interventions are, of course, important too as highlighted in several contributions.

Challenges

While this growing evidence reflects significant progress, the research on early childhood development and interventions to support it still faces several key challenges. First, we need a deeper understanding of child development over the early years. Second, as parents are so key in the early years, we need a better understanding of what drives parenting practices and choices about resources like childcare centers, preschools, and schools as well as subjective beliefs, the balance of power within households, and social norms. Third, we need to understand what determines teachers’ behaviors, including their interactions with parents.

For this research to be influential, we also need to understand how to design interventions that are sustainable and effective at scale. As many of these policies aim to change individual behaviors of parents and possibly teachers, the design of the interventions is critical. It is important to convey the relevant messages in ways that can be understood and consistently acted upon. To address these challenges, it is necessary to develop richer and better measurement tools to allow better assessment of child development processes and their drivers.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Yale’s Economic Growth Center for support with the editing of this article. Greg Larson offered invaluable editing support.

Endnotes

“Parental Investments and Skills Formation during Infancy and Youth: Long Term Evidence from an Early Childhood Intervention,” Attanasio OP, Cortes D, Maldonado D, Rodriguez-Lesmes P, Charpak N, Tessier R, Ruiz JG, Gallego J, Hernandez T, Uriza F, Gallegos A. NBER Working Paper 32851, August 2024.

The Orphans of Davenport: Eugenics, the Great Depression, and the War over Children’s Intelligence, Brookwood M. New York: Liveright, 2021.

For a survey of some of these interventions, see “Fostering and Measuring Skills: Interventions That Improve Character and Cognition,” Heckman JJ, Kautz T. NBER Working Paper 19656, December 2013, and in The Myth of Achievement Tests: The GED and the Role of Character in American Life, Heckman JJ, Humphries JE, Kautz T, editors, pp. 341–430. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2014.

“Improving Cognitive Ability in Chronically Deprived Children,” McKay H, Sinisterra L, McKay A, Gomez H, Lloreda P. Science 200(4339), April 1978, pp. 270–278.

“Long-Term Effects of Food Supplementation and Psychosocial Intervention on the Physical Growth of Colombian Infants at Risk of Malnutrition,” Super CM, Herrera MG, Mora JO. Child Development 61(1), February 1990, pp. 29–49.

“Nutritional Supplementation, Psychosocial Stimulation, and Mental Development of Stunted Children: The Jamaican Study,” Grantham-McGregor SM, Powell CA, Walker SP, Himes JH. Lancet 338(758), July 1991, pp. 1–5.

“Labor Market Returns to an Early Childhood Stimulation Intervention in Jamaica,” Gertler P, Heckman J, Pinto R, Zanolini A, Vermeersch C, Walker S, Chang SM, Grantham-McGregor S. Science 344(6187), May 2014, pp. 998–1001.

“The Reach Up Parenting Program, Child Development, and Maternal Depression: A Meta-analysis,” Jervis P, Coore-Hall J, Pitchik HO, Arnold CD, Grantham-McGregor S, Rubio-Codina M, Baker-Henningham H, Fernald LCH, Hamadani J, Smith JA, Trias J, Walker SP. Pediatrics 151(Supplement 2), May 2023.

“Estimating the Production Function for Human Capital: Results from a Randomized Control Trial in Colombia,” Attanasio O, Cattan S, Fitzsimons E, Meghir C, Rubio-Codina M. NBER Working Paper 20965, May 2019, and American Economic Review 110(1), January 2020, pp. 48–85.

“From Quantity to Quality: Delivering a Home-Based Parenting Intervention Through China’s Family Planning Cadres,” Sylvia S, Warrinnier N, Luo R, Yue A, Attanasio O, Medina A, Rozelle S. The Economic Journal 131(635), April 2021, pp. 1365–1400.

“Comparing China REACH and the Jamaica Home Visiting Program,” Zhou J, Heckman JJ, Liu B, Lu M, Chang SM, Grantham-McGregor S. NBER Working Paper 30529, October 2022, and Pediatrics 151(Supplement 2), May 2023.

“Early Stimulation and Enhanced Preschool: A Randomized Trial,” Meghir C, Attanasio O, Jervis P, Day M, Makkar P, Behrman J, Gupta P, Pal R, Phimister A, Vernekar N, Grantham-McGregor S. Pediatrics 151(Supplement 2), May 2023.

“Impacts 2 Years After a Scalable Early Childhood Development Intervention to Increase Psychosocial Stimulation in the Home: A Follow-Up of a Cluster Randomised Controlled Trial in Colombia,” Andrew A, Attanasio O, Fitzsimons E, Grantham-McGregor S, Meghir C, Rubio-Codina M. PLOS Medicine 15(4), April 2018.

Meghir C, Attanasio O, Jervis P, Day M, Makkar P, Behrman J, Gupta P, Pal R, Phimister A, Vernekar N, Grantham-McGregor S, ibid.

“Early Childhood Intervention for the Poor: Long Term Outcomes,” Andrew A, Attanasio O, Augsburg B, Cardona-Sosa L, Day M, Giannola M, Grantham-McGregor S, Jervis P, Meghir C, Rubio-Codina M. NBER Working Paper 32165, February 2024.

“Six-Year Follow-up of Childhood Stimulation on Development of Children With and Without Anemia,” Jamal Hossain S, Tofail F, Fardina Mehrin S, Hamadani JD. Pediatrics 151(Supplement 2), May 2023.

“Estimating the Technology of Cognitive and Noncognitive Skill Formation,” Cunha F, Heckman J, Schennach S. Econometrica 78(3), May 2010, pp. 883–931.

“Child Development in the Early Years: Parental Investment and the Changing Dynamics of Different Dimensions,” Attanasio O, Bernal R, Giannola M, Nores M. NBER Working Paper 27812, September 2020.

Unequal Childhoods: Class, Race, and Family Life, Lareau A. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2011. Our Kids: The American Dream in Crisis, Putnam RD. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2016.

“Subjective Parental Beliefs: Their Measurement and Role,” Attanasio O, Cunha F, Jervis P. NBER Working Paper 26516, August 2024.

“You Are What Your Parents Expect: Height and Local Reference Points,” Wang F, Puentes E, Behrman JR, Cunha F. Journal of Econometrics 243(1-2), July 2024, Article 105269.

“Maternal Subjective Expectations about the Technology of Skill Formation Predict Investments in Children One Year Later,” Cunha F, Elo I, Culhane J. Journal of Econometrics 231(1), November 2022, pp. 3–32.

“Why Don’t Poor Families Move? A Spatial Equilibrium Analysis of Parental Decisions with Social Learning,” Bellue S. CREST Working Paper Series, March 2024.

“Economics and Measurement: New Measures to Model Decision Making,” Almås I, Attanasio OP, and Jervis P. NBER Working Paper 30839, January 2023, and Econometrica 92(4), July 2024, pp. 979–985.

“Parental Investments and Intra-household Inequality in Child Human Capital: Evidence from a Survey Experiment,” Giannola M. The Economics Journal 134(658), February 2024, pp. 671–727.

“Imagine Your Life at 25: Gender Conformity and Later-Life Outcomes,” Ayyar S, Bolt U, French E, O’Dea C. NBER Working Paper 32789, August 2024.

“Public Childcare, Labor Market Outcomes of Caregivers, and Child Development: Experimental Evidence from Brazil,” Attanasio O, Paes de Barros R, Carneiro P, Evans DK, Lima L, Olinto P, Schady N. NBER Working Paper 30653, June 2024.

“Preschool Quality and Child Development,” Andrew A, Attanasio O, Bernal R, Cardona-Sosa L, Krutikova S, Rubio-Codina M. NBER Working Paper 26191, May 2022, and Journal of Political Economy 132(7), July 2024, pp. 2304–2345.

“Longitudinal Causal Impacts of Preschool Teacher Training on Ghanaian Children’s School Readiness: Evidence for Persistence and Fade-Out,” Wolf S, Aber JL, Behrman JR, Peele M. Developmental Science 22(5), September 2019.

“Starting Strong: Medium- and Longer-run Benefits of Mexico’s Universal Preschool Mandate,” Behrman JR, Gomez-Carrera R, Parker SW, Todd PE, Zhang W. Working paper, University of Maryland, June 2024.