Program Report: Children and Families

On July 1, the Program on Children was renamed the Program on Children and Families. This change, which better captures the range of research carried out by its 171 affiliates, in part marks a return to the program’s roots. In 1993, the late Alan Krueger launched an NBER project on the Economics of Families and Children. It subsequently became a program and has been known as the Program on Children since 1997.1 Broadening the program name recognizes the complex web of interactions, economic and otherwise, that involve children. Economic and other forces that affect families can have important effects on children, and developments involving children in turn have significant influence on the wellbeing of adult family members.

In the eight years since our last program report, scholars affiliated with the program have authored 919 working papers on a wide array of topics. We begin this report with a sampling of their continuing research in core areas, such as the long-term consequences of early-life conditions and the effects of public programs affecting children. We then summarize studies on a number of issues that are attracting growing attention, including gun violence, mental health, access to abortion services, and the long-lived effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Consequences of Early-Life Conditions and Policies

It is now well established that events in early life, including in utero, can have both immediate and lasting impacts on children and, therefore, on families. Douglas Almond, Janet Currie, and Valentina Duque review some of the literature and conclude that even relatively mild adverse shocks in early life can have substantial negative impacts. These effects are heterogeneous, reflecting differences in children’s endowments, family budget constraints, and the technologies of production.2 This observation has inspired work investigating how the social safety net influences child health and wellbeing.

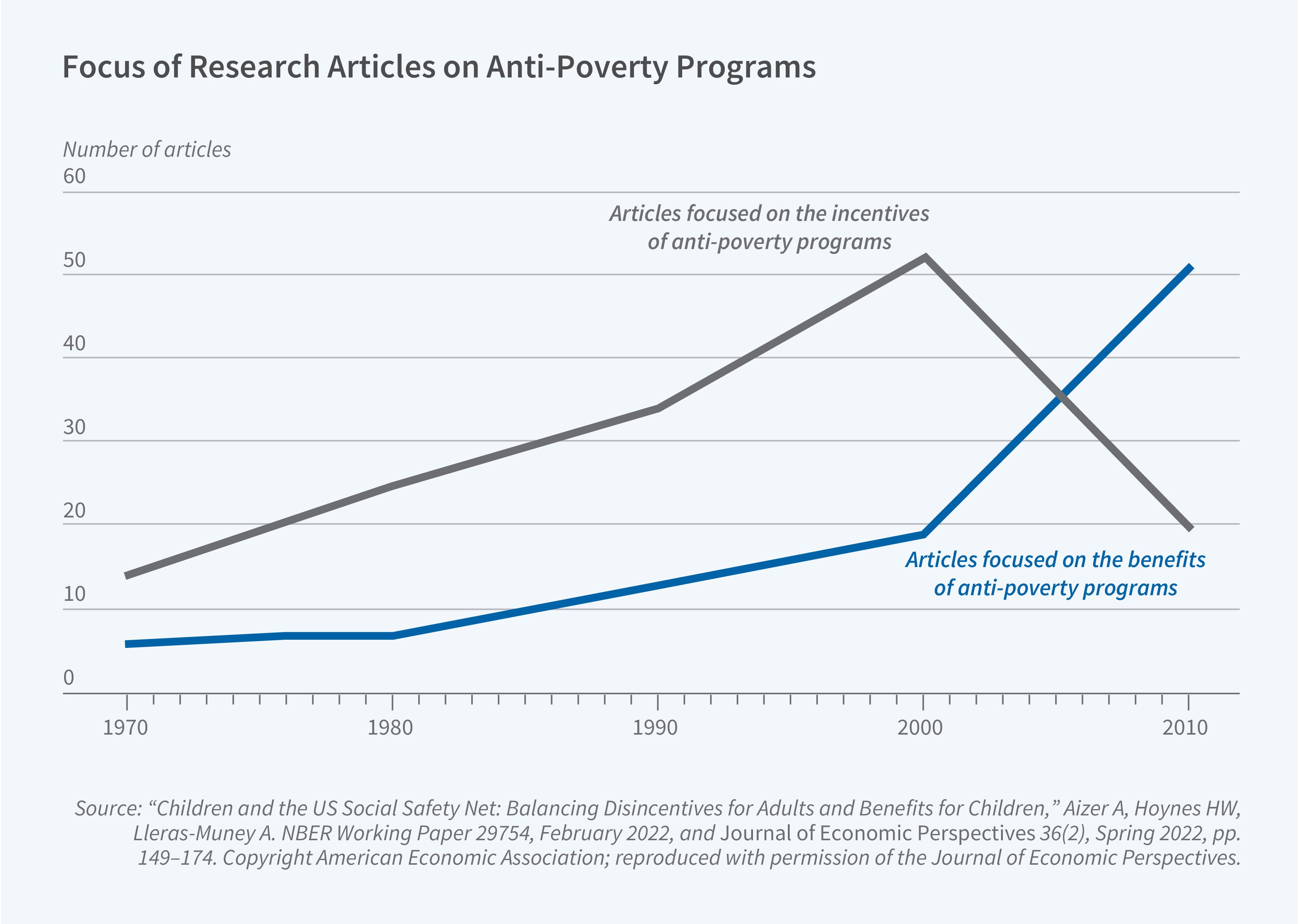

Historically, much of the economic research on the safety net focused on how unconditional assistance to low-income families might affect parental behavior. It was thought that by reducing labor supply and marriage, safety net programs might sustain poverty rather than alleviate it. However, as Anna Aizer, Hilary Hoynes, and Adriana Lleras-Muney show, recent research on the impact of the safety net for children and families has focused more on its impact on child outcomes, as shown in Figure 1.3 This shift in research emphasis roughly coincides with the launch of the NBER research program.

The newer work has shown significant positive effects of safety net programs on short-run child outcomes, as well as on longer-term measures. For example, the Supplemental Security Income (SSI) program is an important safety net program that began to serve larger numbers of children after 1990. Manasi Deshpande and Michael Mueller-Smith find that removing children from the SSI program at age 18 increased the likelihood of criminal charges and incarceration for crimes associated with income generation by 60 percent.4

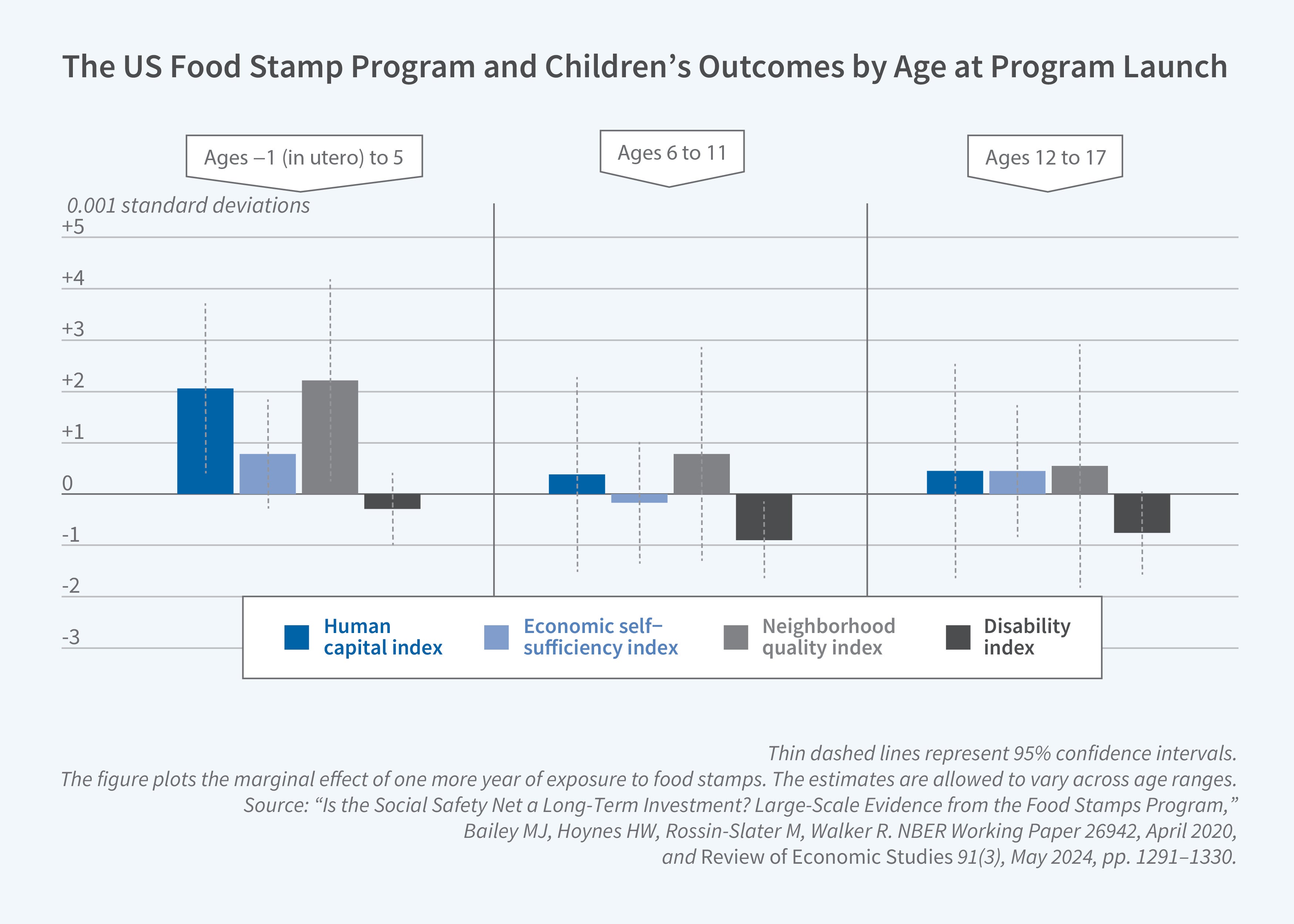

Research on the social safety net has increasingly focused on the long-term impact of initiatives such as the Food Stamp Program rolled out in the US in the 1960s. Martha Bailey, Maya Rossin-Slater, Reed Walker, and Hoynes document significant increases in adult human capital, economic self-sufficiency, and longevity among children exposed to the program early in life, as shown in Figure 2.5

Researchers continue to explore the impact of the safety net on parental behavior. Many papers find little effect of safety net programs on labor supply and marriage rates. These include work by Elizabeth Ananat, Benjamin Glasner, Christal Hamilton, and Zachary Parolin;6 Shari Eli, Aizer, and Lleras-Muney;7 and Jason Cook and Chloe East.8 However, Kevin Corinth, Bruce Meyer, Matthew Stadnicki, and Derek Wu conduct simulations and find that an unconditional child allowance could reduce employment, thus offsetting some of the effects of the allowance in alleviating child poverty.9 Concerns about these effects have contributed to a change in the structure of the US safety net after 1990 so that spending goes increasingly to families with earners who are more likely to have incomes above the poverty line, as documented by Diane Whitmore Schanzenbach and Hoynes.10

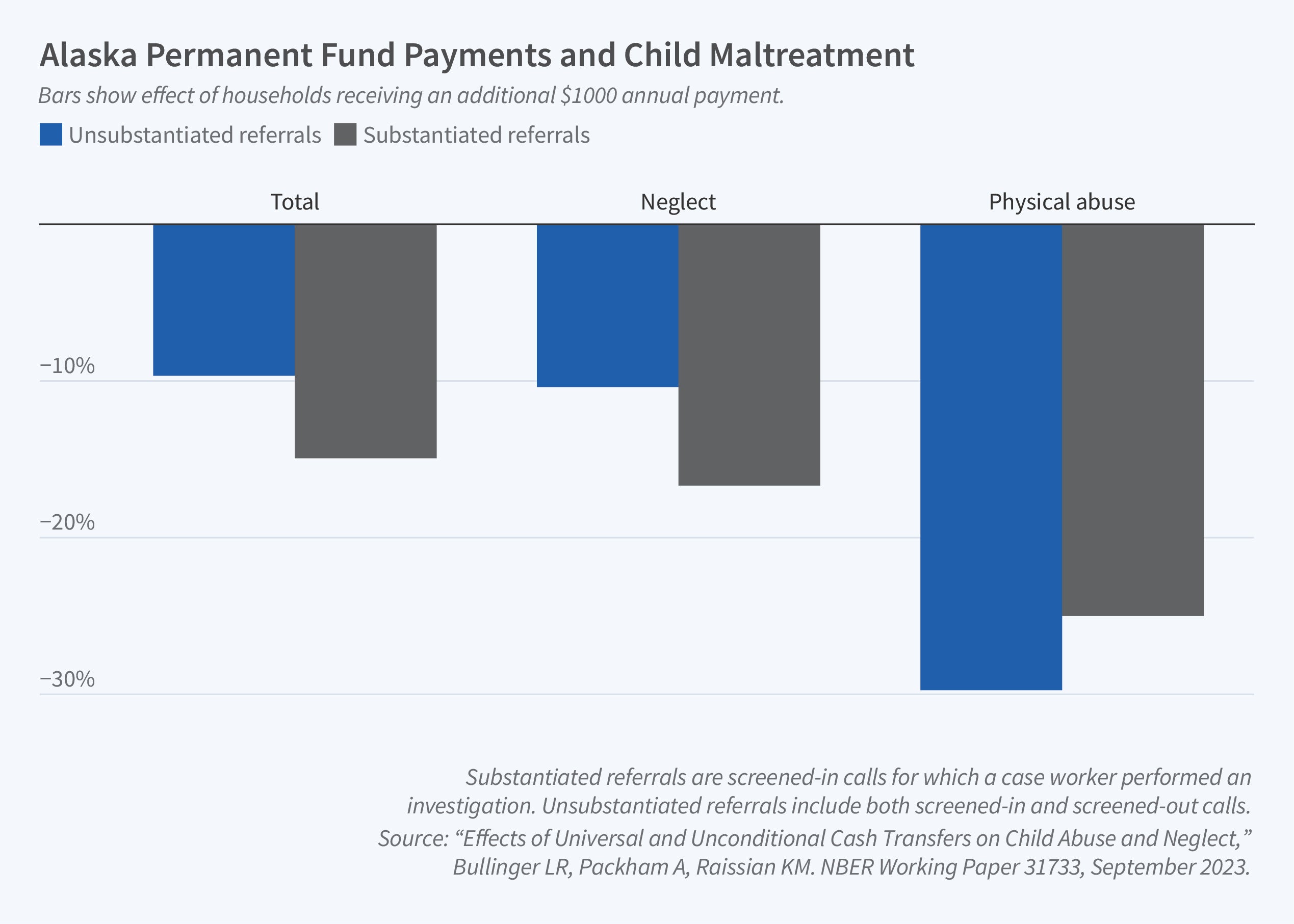

Researchers continue to find large positive effects of cash transfers on children, in part through effects on parental behavior. For example, Lindsey Bullinger, Analisa Packham, and Kerri Raissian show that unconditional cash payments from the Alaska Permanent Fund reduced child maltreatment in that state, as seen in Figure 3.11 The effects of cash transfers on family functioning could potentially be more important than any documented effects on labor supply.

The social safety net can potentially improve parents’ mental health, which may be a pathway for improvements in child outcomes. Lucie Schmidt, Lara Shore-Sheppard, and Tara Watson show in a simulation that a $1,000 increase in cash and food benefits reduced severe psychological distress by 8.4 percent.12 These effects were most pronounced for single mothers with low levels of education. Manudeep Bhuller, Gordon Dahl, Katrine Loken, and Magne Mogstad link parental distress with child wellbeing: A domestic violence incident leads to a 30 percent increase in mental health visits among adult victims and a 19 percent increase in such visits among victims’ children.13

Early Childhood Education

Promising results from two model programs implemented in the US in the 1960s helped to generate significant interest in early childhood education. Work by Jorge Luis García, James Heckman, and Victor Ronda documents the lasting effects of one such program for African American participants and their children. They find that both parents and children completed more schooling and were more likely to be employed later in life.14

Since the first evaluations of these small model programs, other work examining the impact of the Head Start program, which now serves nearly 800,000 children, has also documented significant long-term benefits. Shuqiao Sun, Breden Timpe, and Bailey use restricted linked census data and the roll-out of Head Start across counties to estimate that access to Head Start led to a half-year increase in schooling and a 40 percent increase in college completion.15

While evaluations of small model programs and Head Start suggest positive and long-lasting gains, some other early childhood programs have smaller benefits. Elizabeth Cascio reviews the research and concludes that the effectiveness of early childhood education depends on the quality of the program and the environment that children would have spent time in absent the program.16 Greg Duncan, Ariel Kalil, Mari Rege, and Mogstad explore the heterogeneity in estimated impacts and conclude that investments in skill-specific curricula may be especially important.17

Variation in the quality of early childcare environments can have implications for inequality and social mobility. Sarah Flood, Joel McMurry, Aaron Sojourner, and Matthew Wiswall find that children from families with higher socioeconomic status (SES) are more likely to receive high-quality care which may exacerbate inequalities.18 Jonathan Borowsky, Jessica Brown, Elizabeth David, Chloe Gibbes, Chris Herbst, Sojourner, Erdal Tekin, and Wiswall model the implications of expanding childcare subsidies for low-income families and conclude that it would increase maternal employment and shift more low-income children into high-quality care.19

Health Insurance and Healthcare

Several recent studies find positive impacts of access to medical care, especially for historically marginalized Black children. Esra Kose, Siobhan O’Keefe, and Maria Rosales-Rueda demonstrate that increasing access to medical care via the rollout of community health centers improved birth outcomes.20 Despite the demonstrated benefits of public health insurance coverage during pregnancy, undocumented women remain largely ineligible in the United States. Work by Sarah Miller, Laura Wherry, and Gloria Aldano shows that Medicaid coverage of undocumented women increases prenatal care, with positive impacts on birth weight.21

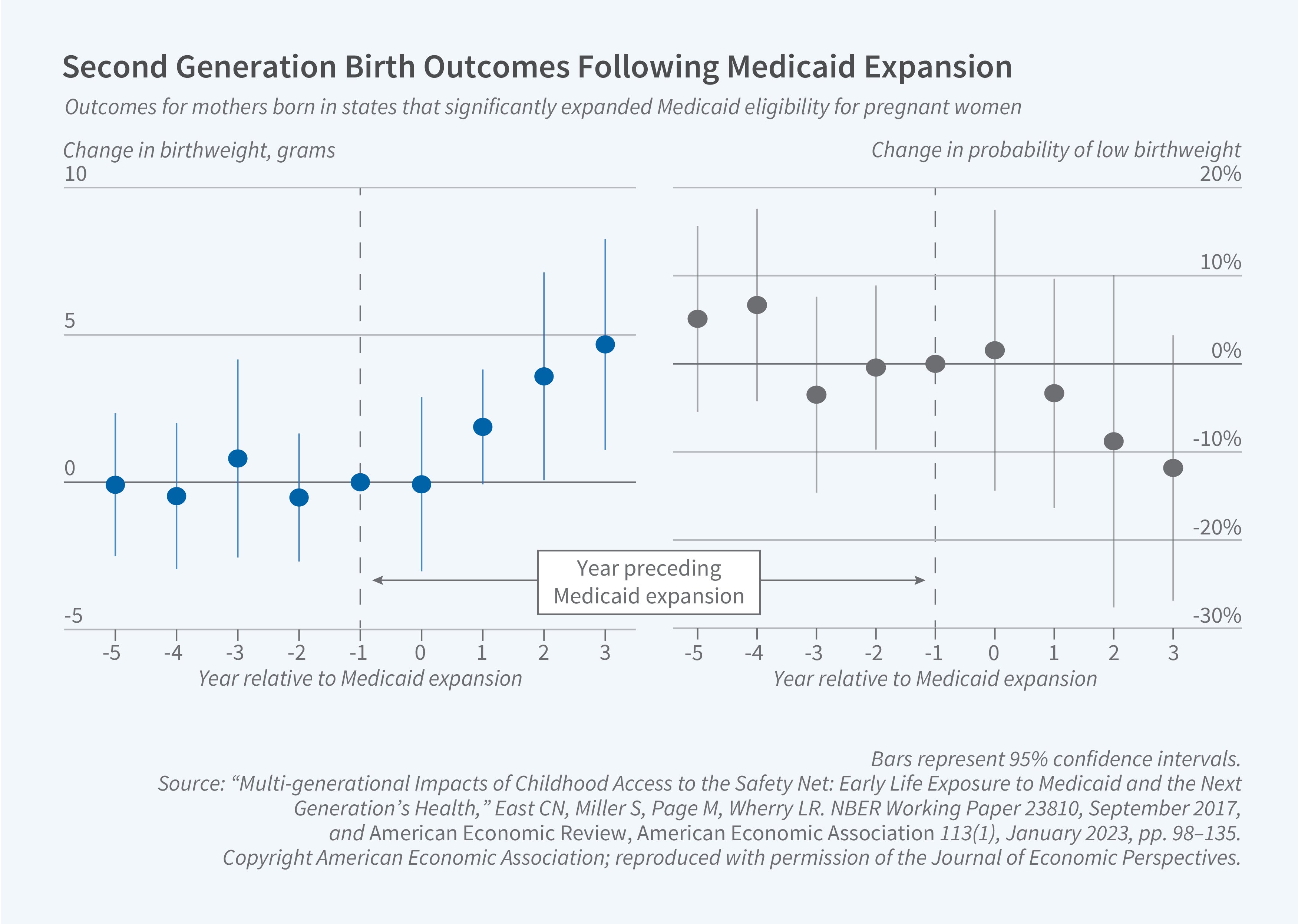

Expansions in Medicaid access can even have intergenerational impacts. East, Marianne Page, Wherry, and Miller estimate the intergenerational impact of Medicaid expansions in utero and in early life. They document that the offspring of children exposed to Medicaid expansions early in life are themselves born healthier, as shown in Figure 4.22

Despite Medicaid’s benefits, many eligible children are not enrolled. Iris Arbogast, Anna Chorniy, and Currie show that regulations increasing the administrative burden of enrollment reduce health insurance coverage among children by six percent in the six months following a new regulation. These effects were especially pronounced among Hispanic children.23

Intergenerational Effects

The growing availability of large datasets that allow linkages across generations has enabled researchers to explore the intergenerational effects of childhood events. Krzysztof Karbownik and Anthony Wray link childhood hospitalizations in 1870–1902 London with later outcomes.24 Boys admitted to the hospital before the age of 12 were three percentage points more likely to experience downward occupational mobility than their brothers, explaining 11 percent of the downward occupational mobility in England at this time. Using historical data on US Civil War veterans linked with that of their children and grandchildren, Dora Costa documents that the grandchildren of men who experienced severe conditions including nutritional deprivation as prisoners of war (POWs)— lost roughly a year of life at age 45 compared to grandsons of veterans who were not POWs.25

Finally, Gordon Dahl and Anne Gielen study a Dutch reform of disability insurance that resulted in an increase in employment and earnings. They find that children of affected adults had increased schooling attainment and better health and labor market outcomes.26

Parental Investments

What explains the intergenerational persistence of shocks to health and wellbeing? One potential mediator is parental investment behavior. García, Frederik Bennhoff, and Duncan Leaf document that a child’s participation in a model early childhood program has spillover benefits to siblings.27 They show that the program affects parental decision-making and likely increases parental investments in all children in the household. Susan Mayer, William Delgado, Lisa Gennetian, and Kalil focus on differences in time investments in children by maternal education. They find that college-educated mothers spend more time, even though they do not appear to place a high value on the time spent.28

There are often important differences in parental investment decisions within families. Rebecca Dizon-Ross and Seema Jayachandran ask how mothers and fathers differ in their propensity to invest in their sons and daughters in Uganda.29 They find that differences in spending across siblings are driven by fathers spending less on daughters.

The opioid epidemic severely disrupted many parents’ capacity to invest in their children. Building on research showing that the epidemic was initially caused by lax prescribing, Kasey Buckles, William Evans, and Ethan Lieber ask how variation across states in the ease with which doctors could prescribe opioids relates to overdose death rates. They conclude that the epidemic led to an additional 1.5 million children living apart from a parent and in a household headed by a grandparent.30

Parents with more resources invest more in their children, but how do parents respond to reductions in household resources? Marianne Bitler, Krista Ruffini, Lisa Schulkind, Barton Willage, Currie, and Hoynes find that when household benefits fall as a result of children aging out of the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children at age 5, the caloric intake of adult women in the household falls but that of children does not, suggesting that mothers protect their children.31

Adolescence

Adolescence is increasingly understood to be a crucial period of growth and development. A number of studies highlight the impact of interventions during this period. Sara Heller evaluates two experiments that provided summer jobs to youth and finds large declines in criminal violence. There was little heterogeneity across implementations of the programs but significant heterogeneity across individual youths: those with the highest probability of negative outcomes benefitted the most.32 Keyoung Lee, Aizer, Eli, and Lleras-Muney study the Great Depression-era Civilian Conservation Corps and find it had significant positive effects on longevity, lifetime earnings, and disability, even though there was little short-term effect on employment or wages.33 Jonathan Guryan et al. find that high-impact tutoring during adolescence can increase test scores by 15–37 percent of a standard deviation, which is comparable to successful early childhood interventions.34 Some recent studies have focused on adolescent girls in developing countries. Eric Edmonds, Benjamin Feigenberg, and Jessica Leight show that teaching life skills to girls in Indian schools reduced drop out.35 Manisha Shah, Jennifer Seager, Joao Montalvao, and Markus Goldstein find that an intervention focused on goal setting reduced intimate partner violence among adolescent girls in sub-Saharan Africa.36

Emerging Areas

Emerging areas of research among program affiliates include child mental health, abortion access, gun violence, and the impact of COVID-19 on families and children.

Mental Health

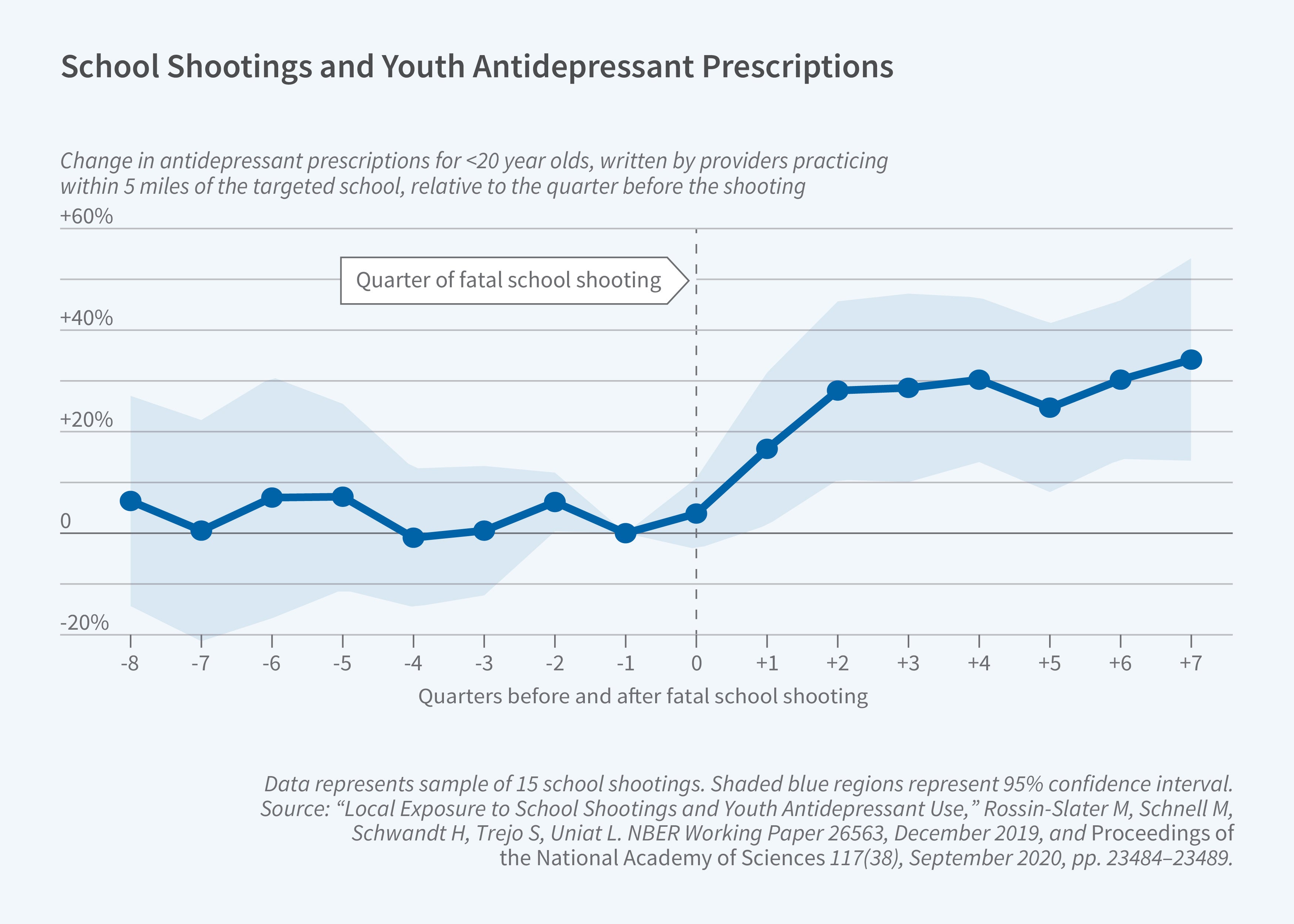

The mental health of children is critical to their wellbeing. Rossin-Slater, Molly Schnell, Hannes Schwandt, Sam Trejo, and Lindsey Uniat find that exposure to school shootings led to an increase in youth antidepressant prescriptions, as shown in Figure 5.37 In follow-up work, Marika Cabral, Bokyoung Kim, Rossin-Slater, Schnell, and Schwandt link exposure to school shootings in Texas to lower educational attainment and worse economic outcomes at age 25.38 This work underscores an important link between violence, mental health, and future economic outcomes.

Monica Deza, Thanh Lu, and Johanna Catherine Maclean use a county-level, two-way fixed effects analysis to show that higher availability of office-based mental healthcare is associated with fewer juvenile arrests.39 But even conditional on access, there are significant SES differences in the types of mental healthcare that children receive. Paul Kurdyak, Jonathan Zhang, and Currie find that among Canadian children with the same health insurance coverage and the same mental health diagnoses, low SES children are more likely to be prescribed drugs with dangerous side effects.40 One way to improve mental health treatment is to encourage adherence to treatment guidelines. Emily Cuddy and Currie show that treating adolescents with mental health conditions in a way that is consistent with treatment guidelines improves health outcomes.41

Perhaps unsurprisingly, there are strong intergenerational correlations in mental health. Aline Bütikofer, Rita Ginja, Karbownik, and Fanny Landaud find that in Norway, a parental mental health diagnosis is associated with a 40 percent higher probability that a child has a mental health diagnosis.42 They also find that early childhood intervention for children whose parents have been diagnosed with a mental health condition can reduce the association between parental and child mental health diagnoses by almost half.

Abortion Access

A growing body of work has explored the ramifications of reduced access to abortion on families and children. Joanna Lahey and Marianne Wanamaker find that abortion restrictions in the late nineteenth century led to increased child mortality.43 Jason Lindo, Caitlin Myers, Andrew Schlosser, and Scott Cunningham show that recent abortion clinic closures in Texas have reduced geographic access and increased births.44 Stephanie Fischer, Heather Royer, and Corey White find that these clinic closures also have reduced take-up of family planning.45 Diana Green Foster, Miller, and Wherry study women who were denied an abortion because they just missed the maximum gestational age cutoff and find that these women experience a large increase in financial distress over the next several years.46

Gun Violence and Its Impacts

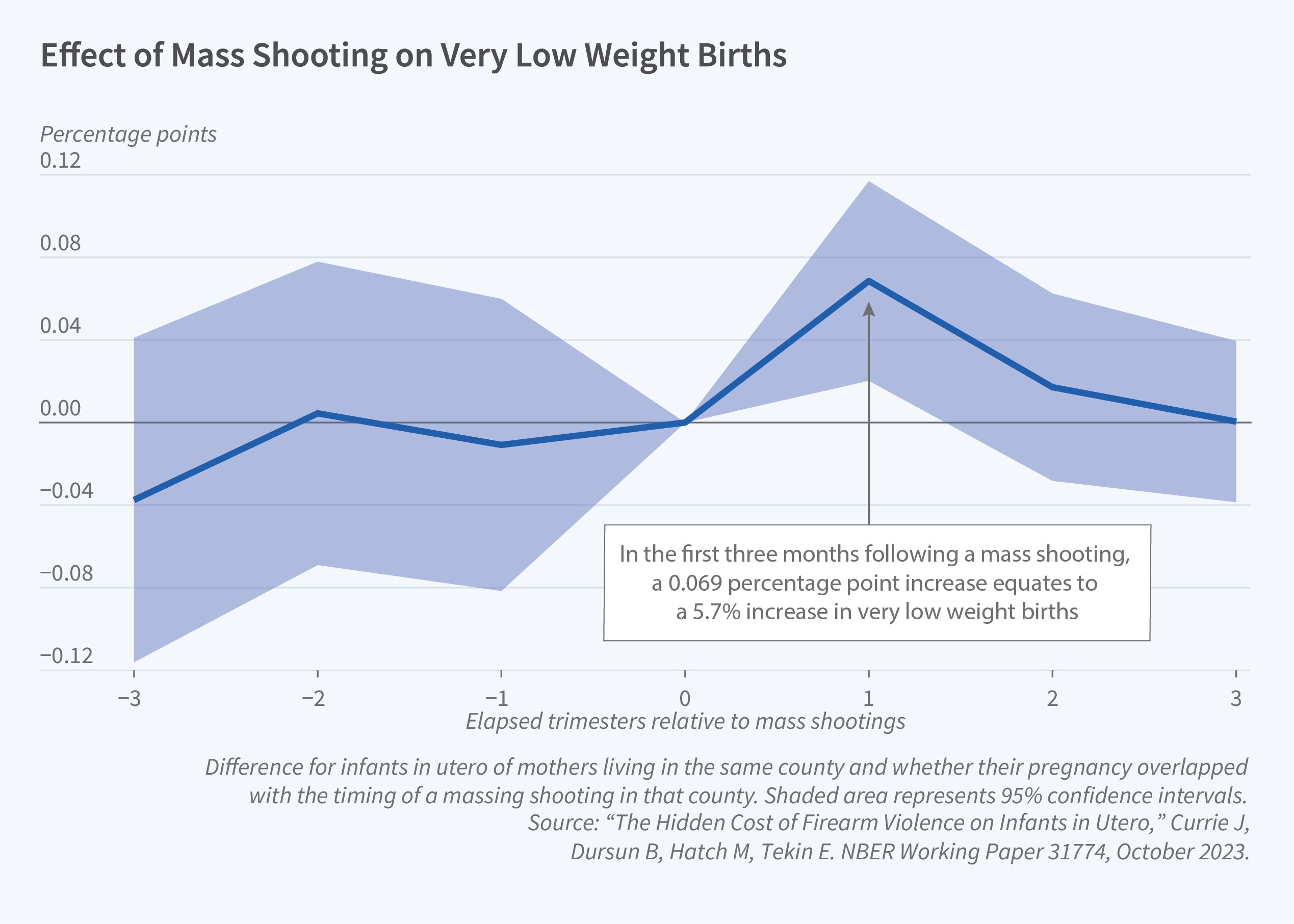

In 2023, deaths from firearms became the leading cause of child death in the US. Previously mentioned work documents the impact of school shootings on adolescent mental health and future economic outcomes. Bahadir Dursun, Michael Hatch, Tekin, and Currie demonstrate that exposure to the Beltway sniper attacks in utero negatively affected newborn health, as shown in Figure 6.47

What explains gun violence, and what can be done to reduce it? Evans, Craig Garthwaite, and Timothy Moore link gun violence today to the crack cocaine epidemic of the 1980s and 1990s, which especially ravaged Black communities. They show that murder rates for young Black males doubled in a city when the crack epidemic started and that it remained 70 percent higher 17 years later largely due to increased gun ownership. They show that today, gun violence explains 10 percent of the racial gap in male life expectancy.48 Monica Bhatt, Max Kapustin, Marianne Bertrand, Christopher Blattman, and Heller evaluate a program that provides paid employment combined with therapy and other social supports to at-risk, young, primarily Black men and find that it reduced shooting and homicide arrests by 65 percent.49

COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic significantly disrupted schooling, causing alarming declines in test scores as well as concerns about behavior and mental health. Clare Halloran, Claire Hug, Rebecca Jack, and Emily Oster find that during the 2021–22 school year, 20 percent of English test score losses and 37 percent of math losses were recovered.50 Anna Gassman-Pines, Ananat, John Fitz-Henley II, and Jane Leer use parent survey data to document that remotely schooled children experienced more disruption and displayed worse behavior.51 Benjamin Hansen, Joseph Sabia, and Jessamyn Schaller find that teen suicide rates plummeted in March 2020, when the pandemic closed schools, and rose when schools reopened.52

Multiple studies have measured the pandemic’s impact on fertility. Melissa Schettini Kearney and Phillip Levine document a drop of nearly 100,000 births between August 2020 and February 2021, followed by a rebound of about 30,000 births between March and September 2021.53 Bailey, Currie, and Schwandt show that 60 percent of the decline was driven by births to foreign-born mothers. Moreover, an initial decline of 30,000 in births to native-born mothers was more than offset by an increase of 71,000 births by 2021.54

Concluding Comments

Economists have long been interested in children and families, but research was scattered across subdisciplines. Development economists thought about stunting and malnutrition, labor economists researched education and discrimination, health economists focused on medical care, demographers studied fertility, and public economists emphasized transfer programs. The Program on Children and Families unites these perspectives and promotes cross-fertilization. The result can be seen in the increasing number of studies that examine multiple outcomes and in the growing internationalization of the field. This richness of perspectives has been complemented by remarkable new data combining information from multiple sources in order to enable research spanning decades, generations, and multiple outcomes. In the coming decade, these sources may facilitate research into vulnerable groups that have seldom been studied, including Native American children, children suffering homelessness, foster children, and the forcibly displaced.

Endnotes

In October 1993, Krueger convened an NBER meeting on “Economics of Families and Children” (https://www.nber.org/sites/default/files/2019-09/Winter%201993%284%29.pdf, page 20). Krueger was tapped for service at the US Department of Labor the next year, and in December 1994, Lawrence Katz organized a conference that gathered the researchers associated with an NBER grant-supported project on “The Well-Being of Children” (https://www.nber.org/sites/default/files/2019-09/reporter1995-01.pdf, page 43). Katz convened another such meeting in May 1995 (https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/62108/2/1995_summer.pdf, page 39). By November 1996, when the group met again, the project had become the “Program on the Well-Being of Children,” and Jonathan Gruber had been named program director (https://www.nber.org/sites/default/files/2019-09/reporter1997-01.pdf, page 39). Gruber was tapped for a role at the US Treasury shortly thereafter, and Janet Currie became the program director. She organized a November 1997 meeting of the “Program on Children” (https://www.nber.org/sites/default/files/2019-09/reporter1998-01.pdf, page 34). Gruber returned to academia, and to his role as program director, in 1998 and organized a November 1998 meeting of the “Program on Children” (https://www.nber.org/sites/default/files/2019-08/winter1998-1999_1.pdf, page 42).

“Childhood Circumstances and Adult Outcomes: Act II,” Almond D, Currie J, Duque V. NBER Working Paper 23017, January 2017, and Journal of Economic Literature 56(4), December 2018, pp. 1360–1446.

“Children and the US Social Safety Net: Balancing Disincentives for Adults and Benefits for Children” Aizer A, Hoynes HW, Lleras-Muney A. NBER Working Paper 29754, February 2022, and Journal of Economic Perspectives 36(2), Spring 2022, pp. 149–174.

Does Welfare Prevent Crime? The Criminal Justice Outcomes of Youth Removed from SSI,” Deshpande M, Muller-Smith MG. NBER Working Paper 29800, February 2022, and The Quarterly Journal of Economics 137(4), November 2022, pp. 2263–2307.

Is the Social Safety Net a Long-Term Investment? Large-Scale Evidence from the Food Stamps Program,” Bailey MJ, Hoynes HW, Rossin-Slater M, Walker R. NBER Working Paper 26942, April 2020, and The Review of Economic Studies 91(3), May 2024, pp. 1291–1330.

Effects of the Expanded Child Tax Credit on Employment Outcomes: Evidence from Real-World Data from April to December 2021,” Ananat E, Glasner B, Hamilton C, Parolin Z. NBER Working Paper 29823, March 2022.

The Incentive Effects of Cash Transfers to the Poor,” Aizer A, Eli S, Lleras-Muney A. NBER Working Paper 27523, July 2020.

The Effect of Means-Tested Transfers on Work: Evidence from Quasi-Randomly Assigned SNAP Caseworkers,” Cook JB, East CN. NBER Working Paper 31307, May 2024.

The Anti-Poverty, Targeting, and Labor Supply Effects of Replacing a Child Tax Credit with a Child Allowance,” Corinth K, Meyer BD, Stadnicki M, Wu D. NBER Working Paper 29366, March 2022.

Safety Net Investments in Children,” Hoynes HW, Schanzenback DW. NBER Working Paper 24594, May 2018.

Effects of Universal and Unconditional Cash Transfers on Child Abuse and Neglect,” Bullinger LR, Packham A, Raissian KM. NBER Working Paper 31733, September 2023.

The Effect of Safety Net Generosity on Maternal Mental Health and Risky Health Behaviors,” Schmidt L, Shore-Sheppard L, Watson T. NBER Working Paper 29258, January 2023, and Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 42(3), Summer 2023, pp. 706–736.

Domestic Violence and the Mental Health and Well-being of Victims and Their Children,” Bhuller M, Dahl GB, Loken KV, Mogstad M. NBER Working Paper 30792, December 2022, and The Journal of Human Resources 59(S), April 2024, pp. S152–S186.

The Lasting Effects of Early Childhood Education on Promoting the Skills and Social Mobility of Disadvantaged African Americans,” García JL, Heckman JJ, Ronda V. NBER Working Paper 29057, July 2021, and Journal of Political Economy 131(6), June 2023, pp. 1477–1506.

Prep School for Poor Kids: The Long-Run Impacts of Head Start on Human Capital and Economic Self-Sufficiency,” Bailey MJ, Sun S, Timpe BD. NBER Working Paper 28268, December 2020, and American Economic Review 111(12), December 2021, pp. 3963–4001.

“Early Childhood Education in the United States: What, When, Where, Who, How, and Why,” Cascio E. NBER Working Paper 28722, April 2021.

“Investing in Early Childhood Development in Preschool and at Home,” Duncan G, Kalil A, Mogstad M, Rege M. NBER Working Paper 29985, May 2022.

“Inequality in Early Care Experienced by US Children,” Flood S, McMurry JFS, Sojourner A, Wiswall MJ. NBER Working Paper 29249, September 2021, and Journal of Economic Perspectives 36(2), Spring 2022, pp. 199–222.

“An Equilibrium Model of the Impact of Increased Public Investment in Early Childhood Education,” Borowsky J, Brown JH, Davis EE, Gibbs C, Herbst CM, Sojourner A, Tekin E, Wisall MJ. NBER Working Paper 30140, June 2022.

“Does the Delivery of Primary Health Care Improve Birth Outcomes? Evidence from the Rollout of Community Health Centers,” Kose E, O’Keefe SM, Rosales-Rueda M. NBER Working Paper 30047, May 2022.

“Covering Undocumented Immigrants: The Effects of a Large-Scale Prenatal Care Intervention,” Miller S, Wherry L, Aldana G. NBER Working Paper 30299, July 2022.

“Multi-generational Impacts of Childhood Access to the Safety Net: Early Life Exposure to Medicaid and the Next Generation’s Health,” East CN, Miller S, Page M, Wherry LR. NBER Working Paper 23810, September 2017, and American Economic Review 113(1), January 2023, pp. 98–135.

“Administrative Burdens and Child Medicaid and CHIP Enrollments,” Arbogast I, Chorniy A, Currie J. NBER Working Paper 30580, April 2024, and American Journal of Health Economics 10(2), Spring 2024, pp. 237–271.

“Educational, Labor-market and Intergenerational Consequences of Poor Childhood Health,” Karbownik K, Wray A. NBER Working Paper 26368, February 2021.

“Health Shocks of the Father and Longevity of the Children’s Children,” Costa D. NBER Working Paper 29553, January 2024.

“Persistent Effects of Social Program Participation on the Third Generation,” Dahl GB, Gielen A. NBER Working Paper 32212, March 2024.

“The Dynastic Benefits of Early Childhood Education: Participant Benefits and Family Spillovers,” García JL, Bennhoff FH, Leaf DE. NBER Working Paper 31555, August 2023.

“Education Gradients in Parental Time Investment and Subjective Well-being,” Kalil A, Mayer S, Delgado W, Gennetian LA. NBER Working Paper 31712, September 2023.

“Dads and Daughters: Disentangling Altruism and Investment Motives for Spending on Children,” Dizon-Ross R, Jayachandran S. NBER Working Paper 29912, April 2022.

“The Drug Crisis and the Living Arrangements of Children,” Buckles K, Evans WN, Lieber EMJ. NBER Working Paper 27633, August 2020, and Journal of Health Economics 87, January 2023, Article 102723.

“Mothers as Insurance: Family Spillovers in WIC,” Bitler M, Currie J, Hoynes HW, Ruffini KJ, Schulkind L, Willage B. NBER Working Paper 30112, June 2022, and Journal of Health Economics 91, September 2023, Article 102784.

“When Scale and Replication Work: Learning from Summer Youth Employment Experiments,” Heller S. NBER Working Paper 28705, April 2021, and Journal of Public Economics 209, May 2022, Article 104617.

“Do Youth Employment Programs Work? Evidence from the New Deal,” Aizer A, Eli S, Lleras-Muney A, Lee K. NBER Working Paper 27103, July 2020.

“Not Too Late: Improving Academic Outcomes Among Adolescents,” Guryan J, Ludwig J, Bhatt MP, Cook PJ, Davis JMV, Dodge K, Farkas G, Fryer Jr RG, Mayer S, Pollack H, Steinberg L. NBER Working Paper 28531, March 2021, and American Economic Review 113(3), March 2023, pp. 738–765.

“Advancing the Agency of Adolescent Girls,” Edmonds EV, Feigenberg B, Leight J. NBER Working Paper 27513, July 2020, and The Review of Economics and Statistics 105(4), July 2023, pp. 852–866.

“Sex, Power, and Adolescence: Intimate Partner Violence and Sexual Behaviors,” Shah M, Seager J, Montalvao J, Goldstein M. NBER Working Paper 31624, November 2023.

“Local Exposure to School Shootings and Youth Antidepressant Use,” Rossin-Slater M, Schnell M, Schwandt H, Trejo S, Uniat LM. NBER Working Paper 26563, December 2019, and PNAS 117(38), September 2020, pp. 23484–23489.

“Trauma at School: The Impacts of Shootings on Students’ Human Capital and Economic Outcomes,” Cabral M, Kim B, Rossin-Slater M, Schnell M, Schwandt H. NBER Working Paper 28311, January 2021.

Office-Based Mental Healthcare and Juvenile Arrests,” Deza M, Lu T, Maclean JC. NBER Working Paper 29465, November 2021, and Health Economics 31(S2), August 2022, pp. 69–91.

“Socioeconomic Status and Access to Mental Health Care: The Case of Psychiatric Medications for Children in Ontario Canada,” Currie J, Kurdyak P, Zhang J. NBER Working Paper 30595, October 2022, and Journal of Health Economics 93, January 2024, Article 102841.

“Rules vs. Discretion: Treatment of Mental Illness in US Adolescents,” Cuddy E, Currie J. NBER Working Paper 27890, October 2020.

“(Breaking) Intergenerational Transmission of Mental Health,” Bütikofer A, Ginja R, Karbownik K, Landaud F. NBER Working Paper 31446, July 2023, and The Journal of Human Resources 59(S), April 2024, pp. S108–S151.

“Effects of Restrictive Abortion Legislation on Cohort Mortality Evidence from 19th Century Law Variation,” Lahey JN, Wanamaker MH. NBER Working Paper 30201, July 2022.

How Far Is Too Far? New Evidence on Abortion Clinic Closures, Access, and Abortions,” Lindo JM, Myers C, Schlosser A, Cunningham S. NBER Working Paper 23366, May 2017, and The Journal of Human Resources 55(4), October 2020, pp. 1137–1160.

“The Impacts of Reduced Access to Abortion and Family Planning Services on Abortion, Births, and Contraceptive Purchases,” Fischer S, Royer H, White C. NBER Working Paper 23634, July 2017, and Journal of Public Economics 167, November 2018, pp. 43–68.

“The Economic Consequences of Being Denied an Abortion,” Miller S, Wherry LR, Foster DG. NBER Working Paper 26662, January 2020, and American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 15(1), February 2023, pp. 394–437.

“The Hidden Cost of Firearm Violence on Infants In Utero,” Currie J, Dursun B, Hatch M, Tekin E. NBER Working 31774, March 2024.

“Guns and Violence: The Enduring Impact of Crack Cocaine Markets on Young Black Males,” Evans WN, Garthwaite C, Moore TJ. NBER Working Paper 24819, July 2018, and Journal of Public Economics 206, February 2022, Article 104581.

“Predicting and Preventing Gun Violence: An Experimental Evaluation of READI Chicago,” Bhatt MP, Heller SB, Kapustin M, Bertrand M, Blattman C. NBER Working Paper 30852, January 2023, and The Quarterly Journal of Economics 139(1), February 2024, pp. 1–56.

“Post COVID-19 Test Score Recovery: Initial Evidence from State Testing Data,” Halloran C, Hug CE, Jack R, Oster E. NBER Working Paper 31113, April 2023

“Effects of Daily School and Care Disruptions During the COVID-19 Pandemic on Child Mental Health,” Gassman-Pines A, Ananat E, Fitz-Henley II J, Leer J. NBER Working Paper 29659, January 2022.

“In-Person Schooling and Youth Suicide: Evidence from School Calendars and Pandemic School Closures,” Hansen B, Sabia JJ, Schaller J. NBER Working Paper 30795, December 2022, and The Journal of Human Resources 59(S), April 2024, pp. S227–S255.

“The US COVID-19 Baby Bust and Rebound,” Kearney MS, Levine PB. NBER Working Paper 30000, July 2023, and Journal of Population Economics 36, July 2023, pp. 2145–2168.

“The COVID-19 Baby Bump: The Unexpected Increase in US Fertility Rates in Response to the Pandemic,” Bailey MJ, Curie J, Schwandt H. NBER Working Paper 30569, August 2023.