Program Report: Political Economy, 2023

The mission of the NBER’s Political Economy Program is to provide a forum for the discussion and distribution of theoretical and empirical research that identifies and addresses political constraints on economic problems. The program flourished under the vision and leadership of founding director Alberto Alesina from its launch in 2006 until his untimely death in 2020. As codirectors, we are grateful to him for shaping it into the active research hub it is today. The program currently has 95 affiliates, who have produced more than 1,000 working papers since the last program report, in 2013.

Political Economy is a broad-tent program in terms of methodology, geography, time period, and topics covered. Members study not only what might be thought of as traditional political economy — the links between economics and politics, such as the study by Daron Acemoglu, Suresh Naidu, Pascual Restrepo, and James Robinson of how elections and institutions impact growth1 — but also investigate how forces like moral values and behavioral impulses impact politics and economics. Benjamin Enke’s investigation of morality and voting2 and Pietro Ortoleva and Erik Snowberg’s exploration of the role of overconfidence in political behavior3 are but two examples of the latter.

We cannot cover the full breadth of program affiliates’ output in the decade since the last report. We therefore will not revisit the four topics — institutions, diversity, US elections, and culture — that it highlighted, except to say that they are still highly researched. As one illustration, Alberto Bisin and Paola Giuliano convene a full-day meeting on cultural economics adjacent to the spring program meeting. We highlight instead three different topics on which program affiliates have focused their efforts: political polarization, state capacity, and conflict. All have large welfare significance.

Polarization

Extreme populist parties have gained strength across democratic nations in the years following the 2008–09 financial crisis, and alongside this phenomenon has grown researchers’ interest in polarization. In addition to studying diverging political views, Levi Boxell, Matthew Gentzkow, and Jesse Shapiro document a rise in affective polarization — negative attitudes toward nonmembers of one’s political party — in six of 12 OECD countries investigated, with the greatest increase in the United States.4 [Figure 1] Party identification now seems to operate as a key dimension of individual identity, with research demonstrating a connection between partisanship and a range of nonpolitical behaviors, from Gordon Dahl, Runjing Lu, and William Mullins’s study of fertility5 to Emanuele Collonnelli, Valdemar Pinho Neto, and Edoardo Teso’s look at hiring in Brazil.6

The central concern of the research on polarization is understanding the causes of its rise and underlying drivers. The bulk of the empirical analysis supports a role for three major causes: trade and globalization, ethnocentrism, and the media. Regarding trade, Cevat Aksoy, Sergei Guriev, and Daniel Treisman demonstrate that, across 118 countries, opinions of the incumbent politician diminish as imports increase.7 Moderates are driven out of office in the face of rising Chinese trade exposure, Christian Dippel, Robert Gold, and Stephan Heblich show for Germany;8 and David Autor, David Dorn, Gordon Hanson, and Kaveh Majlesi document for the US.9

Evidence of a role for ethnocentrism in the rise of populism is provided by, among others, Simone Moriconi, Giovanni Peri, and Riccardo Turati, who show that low-skilled immigration has driven nationalistic preferences across 12 European nations since 2007.10 Immigration also decreases support for redistributive policies, according to Alesina, Elie Murad, and Hillel Rapoport,11 contributing to a long literature that seeks to understand why inequality does not predict support for increased redistribution, a puzzle that has great relevance for our understanding of polarization. In fact, Alesina, Armando Miano, and Stefanie Stantcheva find that just having survey respondents think about immigration lowers support for redistribution.12 Jesper Akesson, Robert Hahn, Robert Metcalfe, and Itzhak Rasooly find similar effects for race.13

Outside of the connection with polarization, program affiliates remain interested in how racial, ethnic, religious, and gender identity impact political preferences, behavior, and, most of all, treatment received in the political sphere. Elizabeth Cascio and Na’ama Shenhav analyze 100 years of women’s voting in the United States.14 Across contexts, contributors are exploring how ethnic and religious concordance between representatives and voters impacts receipt of public goods. See, for example, Kaivan Munshi and Mark Rosenzweig on India15 and Brian Beach, Daniel B. Jones, Tate Twinam, and Randall Walsh on California.16 Researchers are also continuing to explore how voters’ voices are suppressed by race, as in Federico Ricca and Trebbi’s work on how endogenous political institutions keep minorities from voting in the present-day US17 and Enrico Cantoni and Vincent Pons’ analysis of voter ID laws.18

Returning to polarization, ethnocentrism and economic causes are not necessarily at odds: Jiwon Choi, Ilyana Kuziemko, Ebonya Washington, and Gavin Wright provide evidence for an interactive role for the two forces in political beliefs.19 Nor are they the only two explanations explored for increased polarization. Political economists have for quite some time been asking questions around how our biases impact how we take in media and how media further our biases. Ester Faia, Andreas Fuster, Vincenzo Pezone, and Basit Zafar study the former20 and Gregory J. Martin and Ali Yurukoglu the latter.21

Increasingly, the field of political economy, like the public’s attention, has also turned to social media and its role in furthering discord. Gene Grossman and Elhanan Helpman model how parties’ ability to push fake news to their supporters increases both policy divergence and suboptimal outcomes.22 Acemoglu, Asuman Ozdaglar, and James Siderius demonstrate platforms’ role in this process, showing that they are incentivized to create algorithms that amplify low-reliability content.23 But even outside of fake news, Renee Bowen, Danil Dmitriev, and Simone Galperti show that our sharing behavior furthers polarization.24 Rafael Di Tella, Ramiro Gálvez, and Ernesto Schargrodsky find that following a political event, in this case the 2019 Argentina presidential debate, only those inside the echo chamber became more polarized.25 On the other hand, intriguingly, Boxell, Gentzkow, and Shapiro describe how polarization has increased most in recent years among demographic groups least likely to use social media.26 Nonetheless, Thomas Fujiwara, Karsten Müller, and Carlo Schwarz find that social media affects vote shares in US elections.27

While there is no consensus on the role of social media in politics, and certainly not on whether social media enhance or diminish welfare more broadly, what is clear is that the role of new media in campaigns, information acquisition, and political movements will be exciting areas of future inquiry, both in relation to and outside of the impact on political polarization. The same is true of other potential drivers of polarization, such as income and wealth inequality.

State (In)Capacity

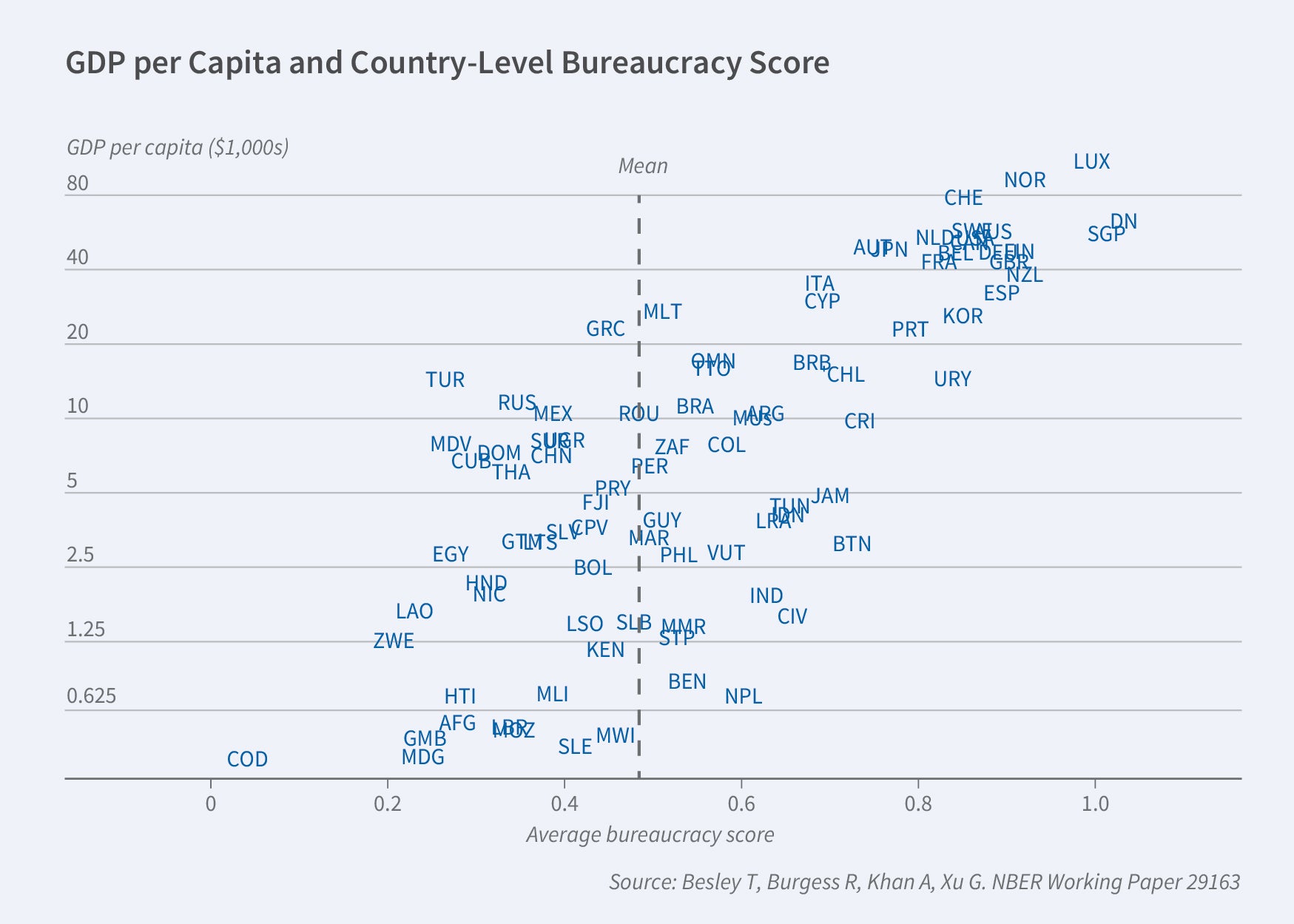

Over the past decade, program affiliates have sought to understand the emergence of weak versus capable states. Studies by Timothy Besley, Robin Burgess, Adnan Khan, and Guo Xu,28 who examine the cross-national relationship between per capita income and the level of government bureaucracy [Figure 2], and Acemoglu, Camilo García-Jimeno, and Robinson who look at the networks of Colombian municipalities are recent examples.29 The field has reached something of a consensus on the importance of strong states in long-run development, as Melissa Dell, Nathaniel Lane, and Pablo Querubin show for northern Vietnam30 and Charles Angelucci, Simone Meraglia, and Nico Voigtländer demonstrate for England.31

A strong state, however, is not necessarily a driver of welfare gains, particularly if the state is in the hands of powerful elites. State capture is therefore another interest, with empirical investigations ranging from Claudio Ferraz, Frederico Finan, and Monica Martinez-Bravo’s work on traditional elites in Brazil32 to Patrick Francois, Ilia Rainer, and Trebbi’s study of autocratic cabinet allocations to ethnic groups in sub-Saharan Africa.33

Another factor that can weaken state capacity is the misalignment of incentives of government officials. Raymond Fisman and Yongxiang Wang find heavy manipulation of accidental death data in China due precisely to this cause.34 Acemoglu, Leopoldo Fergusson, Robinson, Dario Romero, and Juan F. Vargas point to the perils of the lack of state capacity along critical dimensions when the incentives for representatives of the state are high powered.35

In addition to moral hazard, asymmetric information within the government can be a cause of weakness. Ernesto Dal Bó, Finan, Nicholas Li, and Laura Schechter provide experimental evidence of this issue for agricultural inspectors in Paraguay.36 Oriana Bandiera, Michael Carlos Best, Adnan Qadir Khan, and Andrea Prat show how improvements in efficiency arise from the delegation of authority to procurement officers in Pakistan.37

A final factor that can hobble state capacity is corruption, a huge topic of investigation. To provide two examples of its documentation, Fisman and Wang show that politically connected firms in China are allowed to get away with two to three times higher workplace fatality rates than unconnected firms.38 In the US, Filipe R. Campante and Quoc-Anh Do demonstrate that corruption tends to be higher in systems where the centers of political power are more geographically isolated from principals/voters, a finding that suggests that corruption matters to voters.39 Finan and Maurizio Mazzocco demonstrate this explicitly, showing that Brazil’s anti-corruption audits are highly valued by voters notwithstanding their costs.40 In Mexico, Eric Arias, Horacio Larreguy, John Marshall, and Pablo Querubin find that the frequency of malfeasance is important for electoral accountability.41

The most difficult questions about corruption revolve around how to stamp it out and what might be the unintended consequences of eliminating it. Raúl Sanchez de la Sierra, Kristof Titeca, Haoyang Xie, Albert Malukisa Nkuku, and Aimable Amani Lameke present a case study of the internal organization of the traffic police in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, where the effects of anti-corruption efforts are ambiguous and depend on the transfer schemes and quotas allocated between lower-ranked and higher-ranked police officers.42 In El Salvador, Zach Y. Brown, Eduardo Montero, Carlos Schmidt-Padilla, and Maria Micaela Sviatschi find that policies aimed at pacifying and reducing nonaggression among criminal gangs increased extortion.43 Lauren Cohen and Bo Li provide evidence that in the US the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, a statute aimed at curtailing foreign bribery, is misused strategically against foreign firms located in a senator’s state when the senator is up for reelection.44

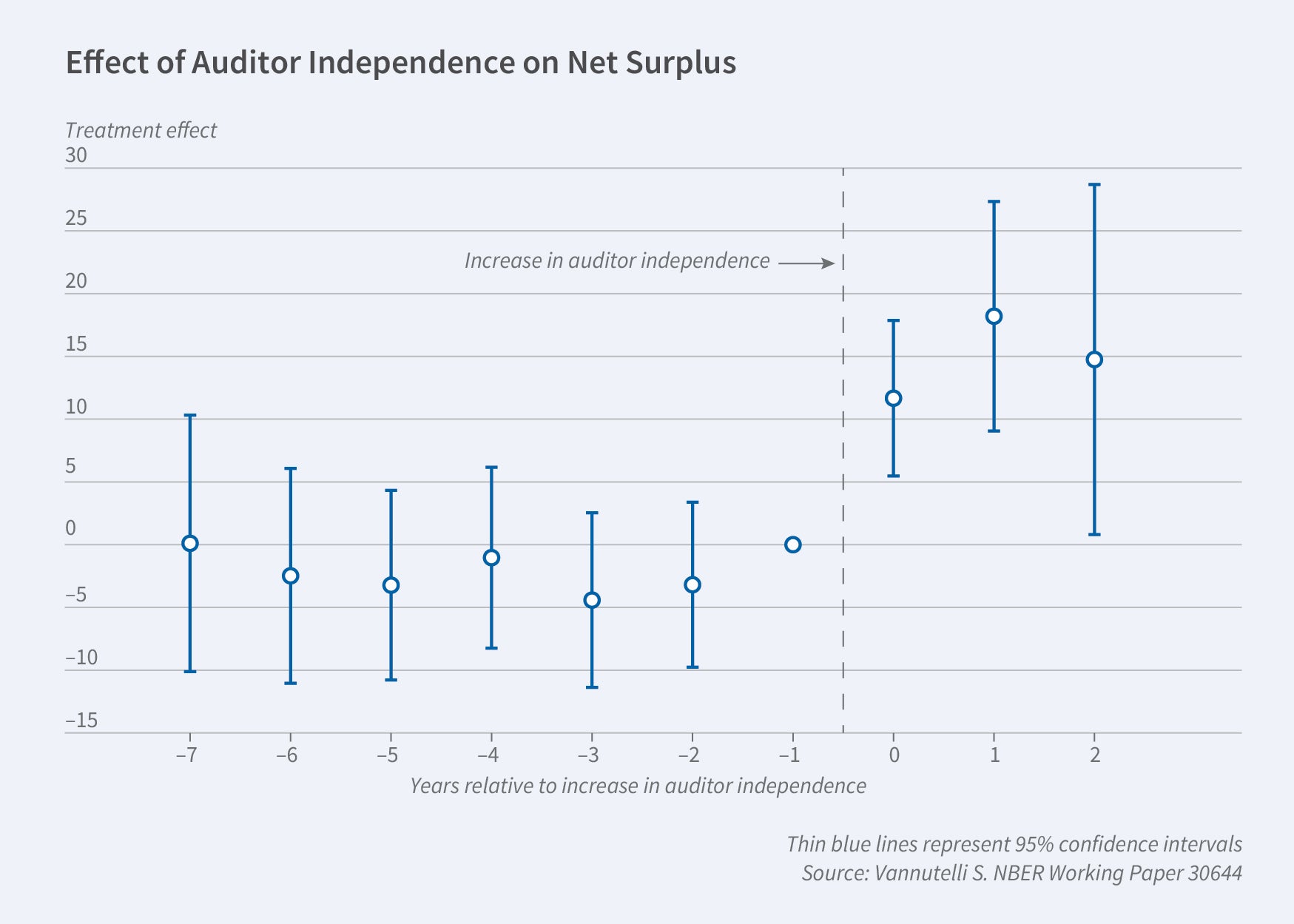

Political capture of public officials, a phenomenon often associated with corruption, has also received growing attention. Xu, Marianne Bertrand, and Burgess demonstrate that social proximity facilitates political capture of bureaucrats in India,45 while Silvia Vannutelli shows that removing the ability of Italian mayors to hire their own financial auditors yields municipal fiscal improvements.46 [Figure 3]

Increasing Conflict and Violence

Since 2013 the world has seen the rise and fall of the Islamic State in the Middle East, heightened conflict in Syria in the aftermath of the Arab Spring, insurgencies in Yemen, Afghanistan, and Nigeria, and Russian invasions of Ukraine, first in 2014 and then on a larger scale in 2022. All these conflicts have far-flung economic, social, and political consequences. Program affiliates have increasingly turned their attention to conflict, beginning with its origins. Acemoglu, Fergusson, and Simon Johnson47 and Cemal Eren Arbatli, Quamrul Ashraf, Oded Galor, and Marc Klemp48 investigate anthropological and economic origins from a broad historical perspective. Other researchers consider cultural origins, including Eoin McGuirk and Marshall Burke in the context of Africa,49 or institutional constraints, like Oendrila Dube and Naidu50 and Antonella Bandiera, Lelys Dinarte Diaz, Juan Miguel Jimenez, Sandra Rozo, and Sviatschi in Latin America.51

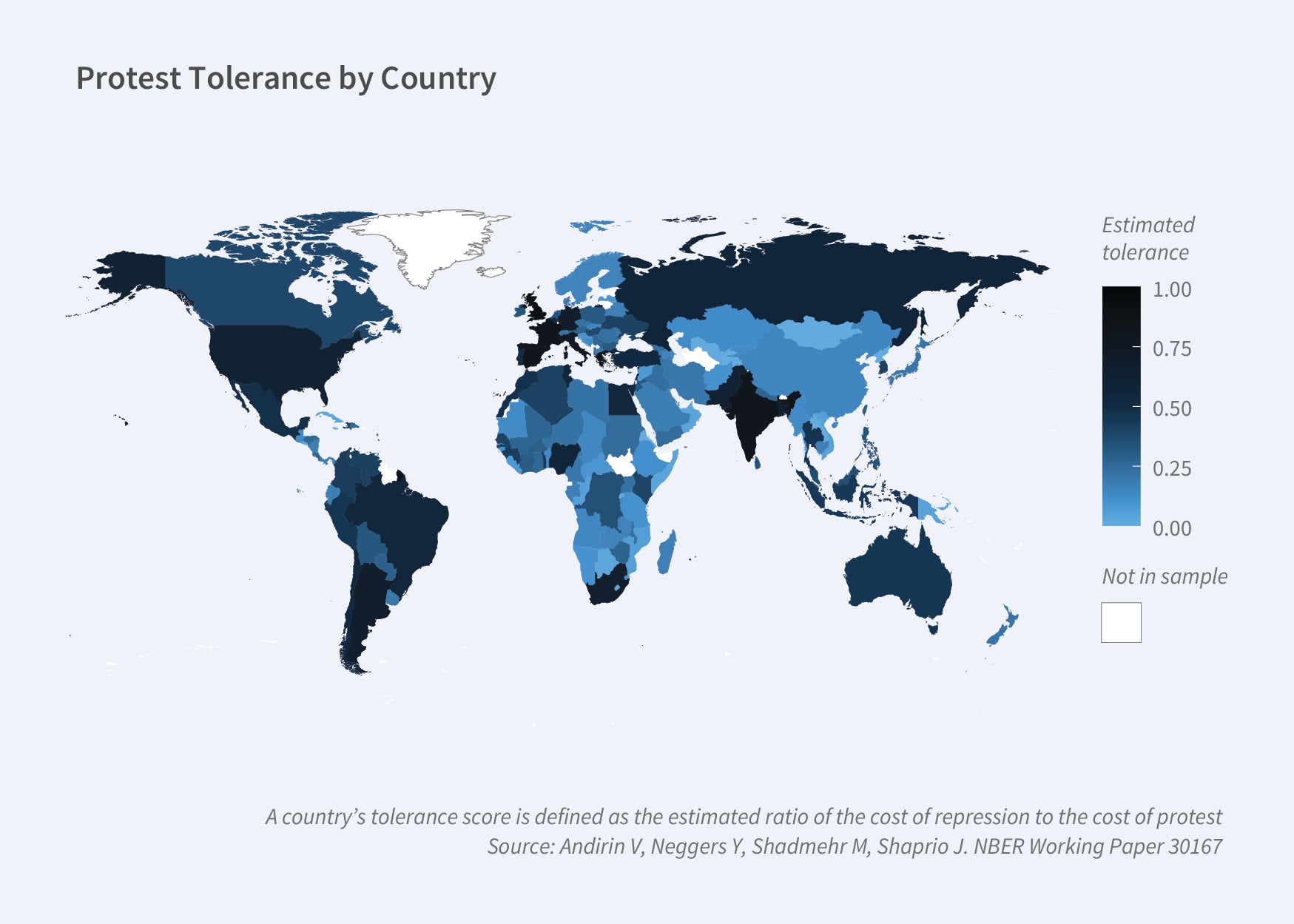

Researchers also seek to understand the incentives and strategies of the actors. Studies by Efraim Benmelech and Esteban Klor52 and Trebbi, Eric Weese, Austin L. Wright, and Andrew Shaver53 focus on the role of insurgent groups in Asia. Veli Andirin, Yusuf Neggers, Mehdi Shadmehr, and Shapiro estimate various regimes’ tolerance for citizen action by studying the frequency of political protests.54 [Figure 4]

Burke, Solomon Hsiang, and Edward Miguel outline the role of climate in conflict.55 Murat Iyigun, Nathan Nunn, and Nancy Qian take the long view, investigating the question empirically over five centuries of conflicts in Europe, North Africa, and the Near East, from 1400 to 1900.56

Increasing attention to the topic of violence has generated closer interactions between political economy and other subfields of economics, particularly development and economic history. Several of the studies cited above focus on developing countries. Similarly, Ying Bai, Ruixue Jia, and Jiaojiao Yang’s work on the role of Zeng Guofan in the Taiping Rebellion in nineteenth century China connects to both subfields.57 Leander Heldring, Robinson, and Parker Whitfill’s study of the political consequences of World War II bombings makes clear the link between political economy and economic history.58

Political economy connects economics to international relations. Nation building, nationalism, and war are at the core of work by Alesina, Bryony Reich, and Alessandro Riboni.59 Conflict studies also bridge the boundary to cultural anthropology. The long-run impact of conflict on cooperation is explored by Michal Bauer, Christopher Blattman, Julie Chytilová, Joseph Henrich, Miguel, and Tamar Mitts60 and Sarah Lowes and Montero61 among others. Dal Bó, Pablo Hernández, and Sebastián Mazzuca explore the trade-off between predation and production in proto-states.62 These linkages are evidence of the sort of interdisciplinary and cross-field conversations that the Political Economy Program has fostered since its launch.

Conclusion

In the words of Alesina and Roberto Perotti: “Political-economy models begin with the assertion that economic policy choices are not made by social planners, who live only in academic papers.” 63 From state polarization to state capacity to war to many of the other topics that we did not cover in this brief report, researchers in political economy have met complex big-picture questions of the last decade with analytical rigor. We anticipate that they will bring this same approach to the high-impact questions of the decades to come, reinforcing the real-world relevance of this field.

Endnotes

“Democracy Does Cause Growth,” Acemoglu D, Naidu S, Restrepo P, Robinson J. NBER Working Paper 20003, March 2014.

“Moral Values and Voting,” Enke B. NBER Working Paper 24268, October 2019.

“Overconfidence in Political Behavior,” Ortoleva P, Snowberg E. NBER Working Paper 19250, July 2013.

"Cross-Country Trends in Affective Polarization,” Boxell L, Gentzkow M, Shapiro J. NBER Working Paper 26669, November 2021.

“Partisan Fertility and Presidential Elections,” Dahl G, Lu R, Mullins W. NBER Working Paper 29058, December 2021.

“Politics at Work,” Colonnelli E, Pinho Neto V, Teso E. NBER Working Paper 30182, June 2022.

“Globalization, Government Popularity, and the Great Skill Divide,” Aksoy Cevat, Guriev S, Treisman D. NBER Working Paper 25062, September 2018.

“Globalization and Its (Dis-)Content: Trade Shocks and Voting Behavior,” Dippel C, Gold R, Heblich S. NBER Working Paper 21812, December 2015.

“Importing Political Polarization? The Electoral Consequences of Rising Trade Exposure,” Autor D, Dorn D, Hanson G, Majlesi K. NBER Working Paper 22637, December 2017.

“Skill of the Immigrants and Vote of the Natives: Immigration and Nationalism in European Elections 2007–2016,” Moriconi S, Peri G, Turati R. NBER Working Paper 25077, September 2018.

“Immigration and Preferences for Redistributioon in Europe,” Alesina A, Murard E, Rapoport H. NBER Working Paper 25562, February 2019.

“Immigration and Redistribution,” Alesina A, Miano A, Stantcheva S. NBER Working Paper 24733, March 2022.

"Race and Redistribution in the United States: An Experimental Analysis,” Akesson J, Hahn R, Metcalfe R, Rasolly I. NBER Working Paper 30426, September 2022.

"A Century of the American Woman Voter: Sex Gaps in Political Participation, Preferences, and Partisanship since Women’s Enfranchisement,” Cascio E, Shenhav N. NBER Working Paper 26709, January 2020.

“Insiders and Outsiders: Local Ethnic Politics and Public Goods Provision,” Munshi K, Rosenzweig M. NBER Working Paper 21720, November 2015.

“Minority Representation in Local Government,” Beach B, Jones D, Twinam T, Walsh R. NBER Working Paper 25192, September 2019.

“Minority Underrepresentation in U.S. Cities,” Ricca F, Trebbi F. NBER Working Paper 29738, February 2022.

“Strict ID Laws Don’t Stop Voters: Evidence from a U.S. Nationwide Panel, 2008–2018,” Cantoni E, Pons V. NBER Working Paper 25522, May 2021.

“Local Economic and Political Effects of Trade Deals: Evidence from NAFTA,” Choi J, Kuziemko I, Washington E, Wright G. NBER Working Paper 29525, November 2021.

“Biases in Information Selection and Processing: Survey Evidence from the Pandemic,” Faia E, Fuster A, Pezone V, Zafar B. NBER Working Paper 28484, February 2021.

“Bias in Cable News: Persuasion and Polarization,” Martin G, Yurukoglu A. NBER Working Paper 20798, June 2016.

“Electoral Competition with Fake News,” Grossman G, Helpman E. NBER Working Paper 26409, October 2019.

“A Model of Online Misinformation,” Acemoglu D, Ozdaglar A, Siderius J. NBER Working Paper 28884, January 2022.

"Learning from Shared News: When Abundant Information Leads to Belief Polarization,” Bowen R, Dmitriev D, Galperti S. NBER Working Paper 28465, March 2022.

“Does Social Media Cause Polarization? Evidence from Access to Twitter Echo Chambers during the 2019 Argentine Presidential Debate,” Di Tella R, Galvez R, Schargrodsky E. NBER Working Paper 29458, November 2021.

“Is the Internet Causing Political Polarization? Evidence from Demographics,” Boxell L, Gentzkow M, Shapiro J. NBER Working Paper 23258, March 2017.

“The Effect of Social Media on Elections: Evidence from the United States,” Fujiwara T, Muller K, Schwarz C. NBER Working Paper 28849, May 2021.

“Bureaucracy and Development,” Besley T, Burgess R, Khan A, Xu G. NBER Working Paper 29163, August 2021.

"State Capacity and Economic Development: A Network Approach,” Acemoglu D, Garcia-Jimeno C, Robinson J. NBER Working Paper 19813, January 2014.

“The Historical State, Local Collective Action, and Economic Development in Vietnam,” Dell M, Lane N, Querubin P. NBER Working Paper 23208, March 2017.

“How Merchant Towns Shaped Parliaments: From the Norman Conquest of England to the Great Reform Act,” Angelucci C, Meraglia S, Voigtländer N. NBER Working Paper 23606, July 2017.

“Political Power, Elite Control, and Long-Run Development: Evidence from Brazil,” Ferraz C, Finan F, Martinez-Bravo M. NBER Working Paper 27456, June 2020.

“The Dictator’s Inner Circle,” Francois P, Rainer I, Trebbi F. NBER Working Paper 20216, June 2014.

The Distortionary Effects of Incentives in Government: Evidence from China’s ‘Death Ceiling’ Program,” Fisman R, Wang Y. NBER Working Paper 23098, January 2017.

“The Perils of High-Powered Incentives: Evidence from Colombia’s False Positives,” Acemoglu D, Fergusson L, Robinson J, Romero D, Vargas J. NBER Working Paper 22617, March 2018.

“Government Decentralization under Changing State Capacity: Experimental Evidence from Paraguay,” Dal Bó E, Finan F, Li N, Schechter L. NBER Working Paper 24879, July 2019.

“The Allocation of Authority in Organizations: A Field Experiment with Bureaucrats,” Bandiera O, Best M, Khan A, Prat A. NBER Working Paper 26733, August 2021.

Return to Text

“The Mortality Cost of Political Connections,” Fisman R, Wang Y. NBER Working Paper 21266, August 2015.

“Isolated Capital Cities, Accountability and Corruption: Evidence from US States,” Campante F, Do Q. NBER Working Paper 19027, May 2013.

Combating Political Corruption with Policy Bundles,” Finan F, Mazzocco M. NBER Working Paper 28683, April 2021.

“Priors Rule: When Do Malfeasance Revelations Help or Hurt Incumbent Parties?” Arias E, Larreguy H, Marshall J, Querubin P. NBER Working Paper 24888, August 2018.

“The Real State: Inside the Congo’s Traffic Police Agency,” Sanchez de la Sierra R, Titeca K, Xie H, Nkuku A, Lameke A. NBER Working Paper 30258, July 2022.

“Market Structure and Extortion: Evidence from 50,000 Extortion Payments,” Brown Z, Montero E, Schmidt-Padilla C, Sviatschi M. NBER Working Paper 28299, February 2023.

“The Political Economy of Anti-Bribery Enforcement,” Cohen L, Li B. NBER Working Paper 29624, December 2021.

“Social Proximity and Bureaucrat Performance: Evidence from India,” Xu G, Bertrand M, Burgess R. NBER Working Paper 25389, October 2018.

“From Lapdogs to Watchdogs: Random Auditor Assignment and Municipal Fiscal Performance,” Vannutelli S. NBER Working Paper 30644, November 2022.

“Population and Civil War,” Acemoglu D, Fergusson L, Johnson S. NBER Working Paper 23322, April 2017.

“Diversity and Conflict,” Arbatli C, Ashrar Q, Galor O, Klemp M. NBER Working Paper 21079, September 2019.

"The Economic Origins of Conflict in Africa,” McGuirk E, Burke M. NBER Working Paper 23056, April 2020.

“Bases, Bullets and Ballots: The Effect of U.S. Military Aid on Political Conflict in Colombia,” Dube O, Naidu S. NBER Working Paper 20213, June 2014.

“Rebel Governance and Development: The Persistent Effects of Distrust in El Salvador,” Bandiera A, Dinarte Diaz L, Jimenez J, Rozo S, Sviatschi M. NBER Working Paper 30488, January 2023.

“What Explains the Flow of Foreign Fighters to ISIS?” Benmelech E, Klor E. NBER Working Paper 22190, April 2016.

“Insurgent Learning,” Trebbi F, Weese E, Wright A, Shaver A. NBER Working Paper 23475, June 2017.

“Measuring the Tolerance of the State: Theory and Application to Protest,” Andirin V, Neggers Y, Shadmehr M, Shapiro J. NBER Working Paper 30167, June 2022.

“Climate and Conflict,” Burke M, Hsiang S, Miguel E. NBER Working Paper 20598, October 2014.

“Winter Is Coming: The Long-Run Effects of Climate Change on Conflict, 1400–1900,” Iyigun M, Nunn N, Qian N. NBER Working Paper 23033, January 2017.

“Web of Power: How Elite Networks Shaped War and Politics in China,” Bai Y, Jia R, Yang J. NBER Working Paper 28667, August 2022.

“The Second World War, Inequality and the Social Contract in Britain,” Heldring L, Robinson J, Whitfill P. NBER Working Paper 29677, February 2022.

“Nation-Building, Nationalism and Wars,” Alesina A, Reich B, Riboni A. NBER Working Paper 23435, May 2017.

“Can War Foster Cooperation?” Bauer M, Blattman C, Chytilova J, Henrich J, Miguel E, Mitts T. NBER Working Paper 22312, June 2016.

“Concessions, Violence, and Indirect Rule: Evidence from the Congo Free State,” Lowes S, Montero E. NBER Working Paper 27893, October 2020.

“The Paradox of Civilization: Pre-Institutional Sources of Security and Prosperity,” Dal Bó E, Hernandez P, Mazzuca S. NBER Working Paper 21829, December 2015.

“The Political Economy of Growth: A Critical Survey of the Recent Literature,” Alesina A, Perotti R. The World Bank Economic Review 8(3), September 1994, pp. 351–371.