Life-Cycle Impacts of Graduating in a Recession

Young adults who enter the labor market during recessions can experience negative impacts to their economic, family, and health outcomes that endure into middle age and beyond. Those who join the workforce in a downturn have lower long-term earnings, higher rates of disability, fewer marriages, less successful spouses, and fewer children. In middle age they also have higher mortality due to lung, liver, and heart disease. The long-lasting effects of labor market shocks to young adults have important implications for assessing the costs of recessions and government interventions.

Young adulthood — the period from age 18 to 25 — is a time of profound changes that affect the entire life cycle. During this time, the vast majority of people transition from adolescent dependence to adult independence. They complete their education or training, enter the labor market, and start families. Economic theory and casual observation suggest that their early life-cycle decisions are highly interdependent and vulnerable to economic shocks. An increasing number of studies in medicine and psychology also show that early adulthood is a critical phase for neurological, social, and psychological development.

Large and recurring shocks like recessions can affect a significant share of young adults who are in this critical phase. A staggering 30 percent — 46 million — of prime-age workers in the US labor force in 2019 entered the market for the first time during a recession year. Business cycles are known to have strong contemporaneous impacts on young adults and their household decisions, including marriage, fertility, and homeownership.1

A growing body of research has shown that entering the labor market in a recession leads to losses in earnings, wages, and employment that persist for about 10 years, and that these losses are larger for less advantaged labor market entrants.2 Yet, recent analysis suggests that an unlucky start could have longer-term consequences. For example, Anna Aizer and coauthors suggests that the effect of economic interventions may last into middle age.3 A small number of studies indicate that some impacts on earnings and health can persist until age 40, and that economic conditions in youth and early adulthood may even affect mortality in middle age.4 Hence, it is important to extend the follow-up period of studying the effect of adverse labor market entry into middle age, and to analyze the effect on noneconomic outcomes.

Studying life-cycle and midlife effects comes with some challenges, however. It requires long follow-up periods and data on a broad range of economic, family, and health outcomes, as well as knowing where and when an individual entered the labor market. To be able to study a range of outcomes over the life cycle with sufficient precision, we develop a new method for harnessing large, repeated cross-sectional survey and vital statistics data. To analyze effects in middle age, we focus on cohorts entering the labor market in US states before, during, and after the 1982 recession — the largest postwar downturn before the Great Recession — from labor market entry until age 50.

Evidence from Recession Graduates

Economic models of career progression, family formation, and health predict that even short-term economic shocks can affect the entire life cycle into middle age. The theory also highlights how family, economic, and health outcomes can influence one another over the life cycle, and helps us understand why some groups may respond differently than others to an initial shock. While standard models of career progression suggest that entering the labor market in a recession has only temporary effects, models in which job search and human capital accumulation occur in sequence can imply long-lasting effects, especially if workers’ ability to adjust declines with age.

Models of marriage and fertility suggest that having fewer labor market opportunities may lead some individuals to start families earlier, especially if income losses are moderate. Marriages induced by unfavorable labor market conditions may be less stable, and persistently lower earnings are predicted to lead to an increase in divorces, lower marriage rates, and reduced fertility. In parallel, economic stress, family instability, and lasting reductions in earnings likely imply lower health investments throughout people’s lives. The cumulative effect on health will result in increasingly greater mortality during middle age, when death rates naturally increase. Poorer health and unstable families will, in turn, tend to depress productivity and are associated with a rise the incidence of work-related disability.

To measure a broad set of outcomes in a comparable fashion over a long period of time, we use National Vital Statistics System data from 1979 to 2016 and population estimates from the US Decennial Census and the American Community Survey (ACS) to compute mortality rates. Information on socioeconomic outcomes, including earnings, labor supply, marital status, divorce, and cohabitation, is derived from the Census, the ACS, and the Current Population Survey. Our mortality analysis is based on more than 900 million person-year observations and over 1.7 million deaths. The analysis of socioeconomic outcomes is based on 7.8 million survey observations.

Our analysis focuses on the impact of fluctuations in the state-level unemployment rate. This provides us with exogenous variation in local labor market conditions and allows us to net out ongoing trends for all cohorts at the national level. To further ensure that we only measure the effect of temporary initial conditions and not the ensuing evolution in regional economies, in an extensive robustness analysis we control for potentially confounding concurrent trends at the state and cohort levels.

One complication is that our cross-sectional data do not contain information on the state or the year in which an individual entered the labor market. Furthermore, people might migrate to a different state before graduating, or time their graduation in response to local economic conditions. These responses could bias the analysis even if we knew the location and time of graduation. To address these measurement and selection issues, we reweight unemployment rates to reflect the economic conditions a cohort would face at graduation if it had migration and education rates similar to those of surrounding cohorts.5 A key advantage of this approach is that it only requires information at the birth-state and birth-year levels and hence can be applied to Vital Statistics, Decennial Census, and ACS data, which otherwise could not be used to study the long-term effects of state-level labor market entry shocks.

Long-Term Impacts on Mortality, Earnings, and Family Lives

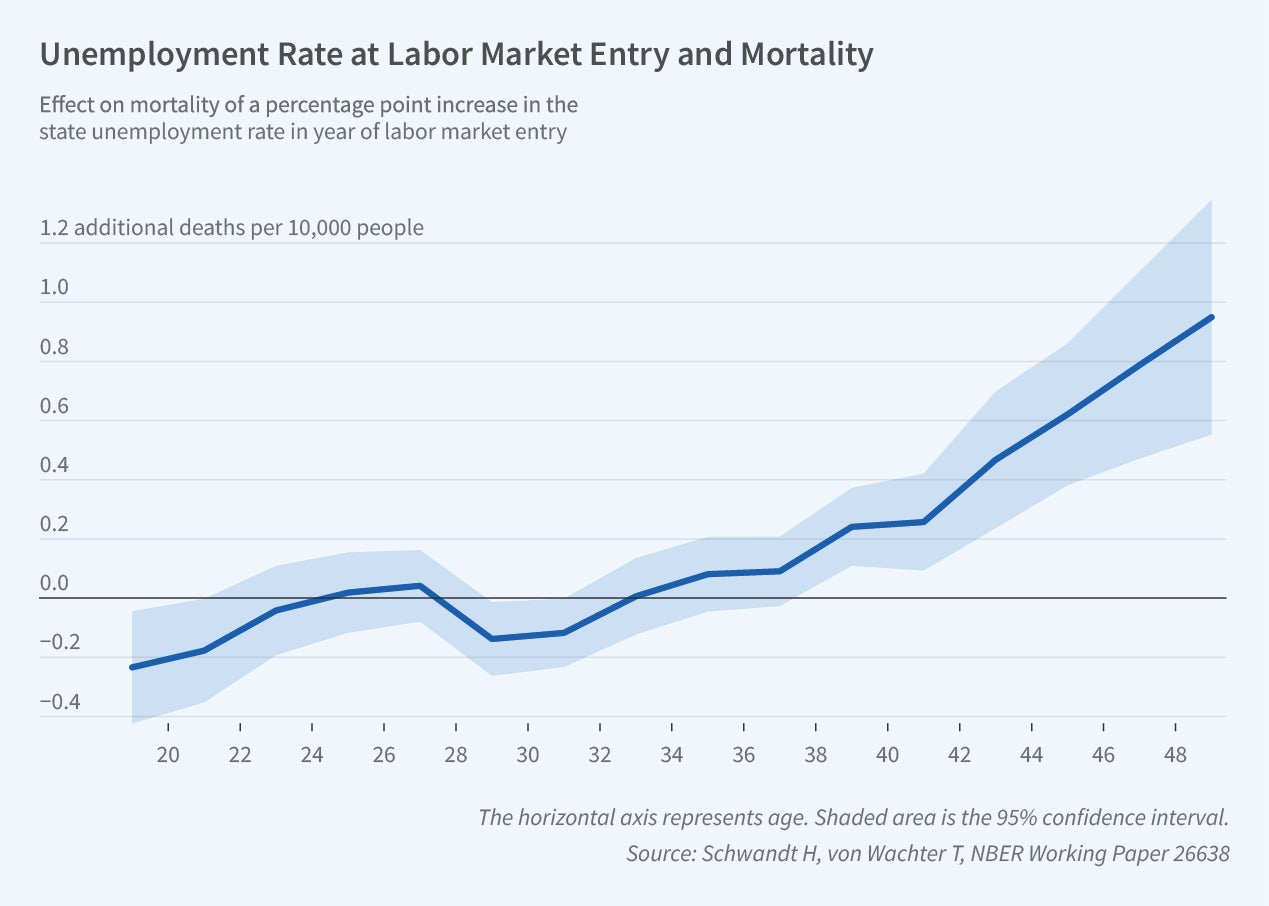

Our modeling approach allows us to display the effect of entering the labor market in a recession graphically. Our figures show the estimated changes in the life-cycle profile of several of our core outcomes due to a 1 percentage point higher unemployment rate at labor market entry. Our first main finding is that a temporarily higher state unemployment rate when young people enter the labor market leads to precisely estimated increases in their mortality in middle age. [Figure 1] The magnitude of these effects is meaningful — if sustained until the end of the cohorts’ lives, a 3.9 percentage point higher unemployment rate, as experienced by the 1982 graduation cohort, would lead to a decrease in life expectancy of six to nine months. Consistent with our findings of increased mortality, we also see a rise in morbidity as measured by a rise in the incidence of self-reported disability and receipt of federal disability insurance in middle age.

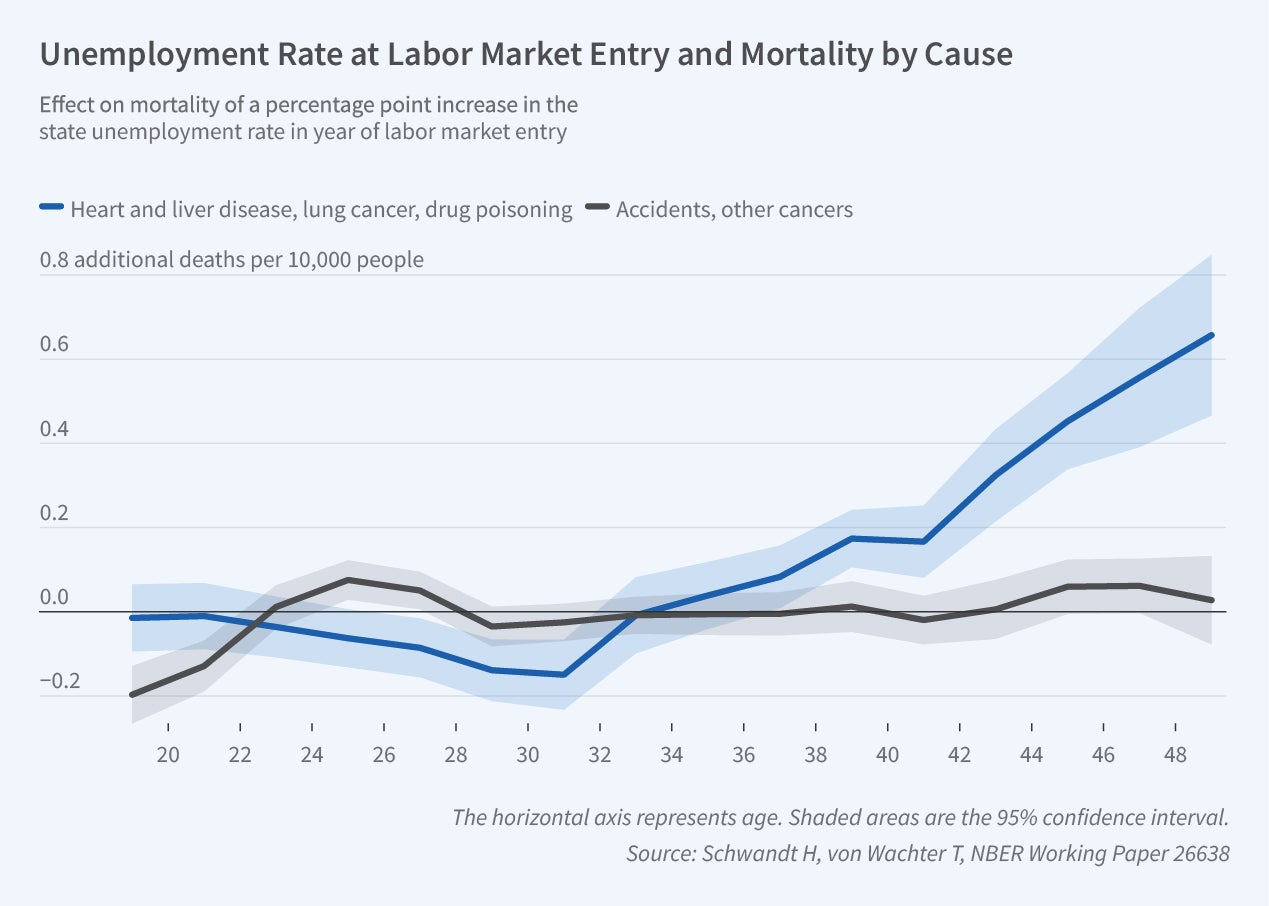

Our second main finding [Figure 2] is that these midlife mortality increases are driven to an important extent by increases in mortality from diseases related to lifestyle and health behaviors, such as lung cancer, liver disease, and drug overdoses. In contrast, we find no long-term effects on other causes of death, such as accidents or cancers other than lung cancer. Interestingly, we find that a recession at the time of labor market entry lowers the mortality of young workers immediately after graduation through a reduction in accidents.

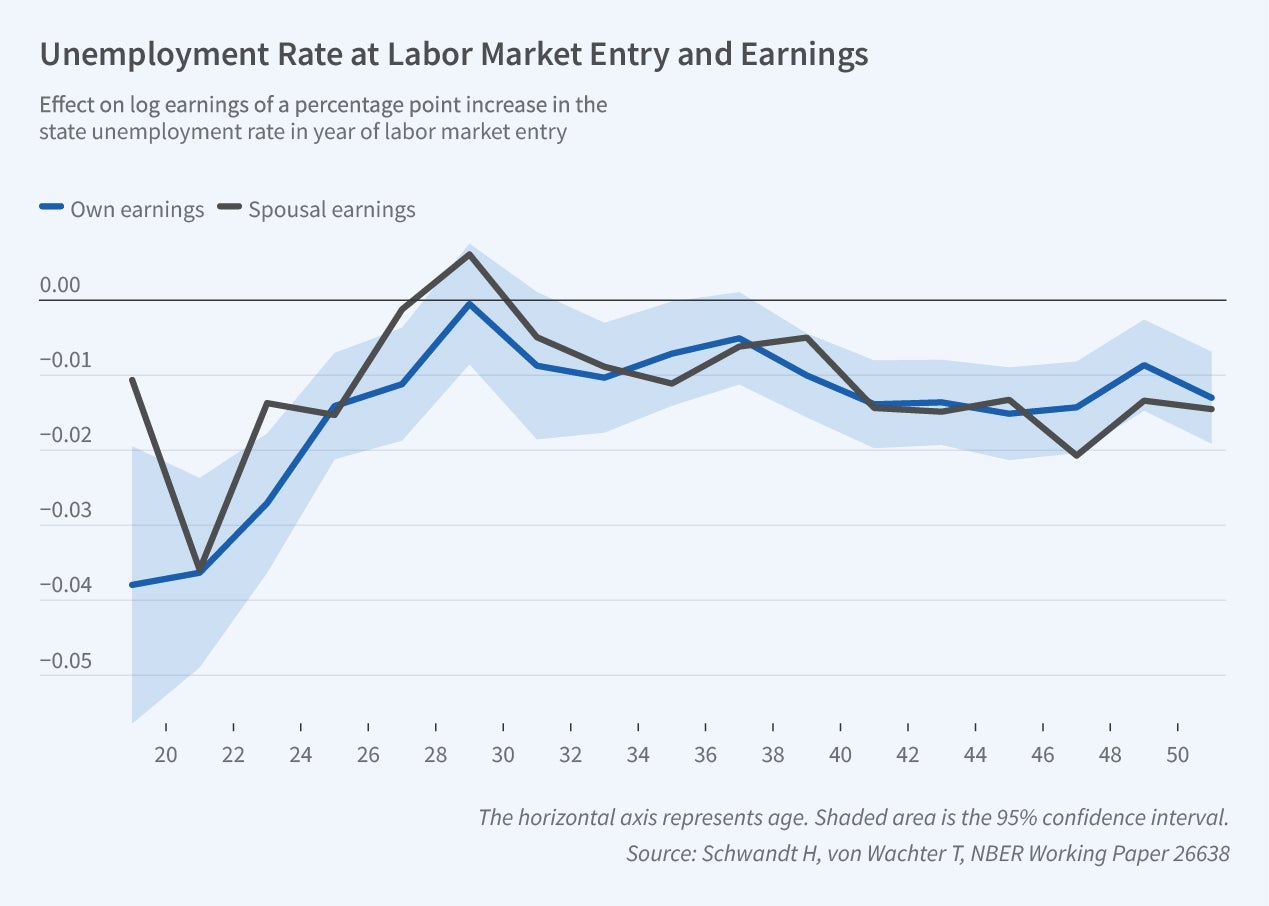

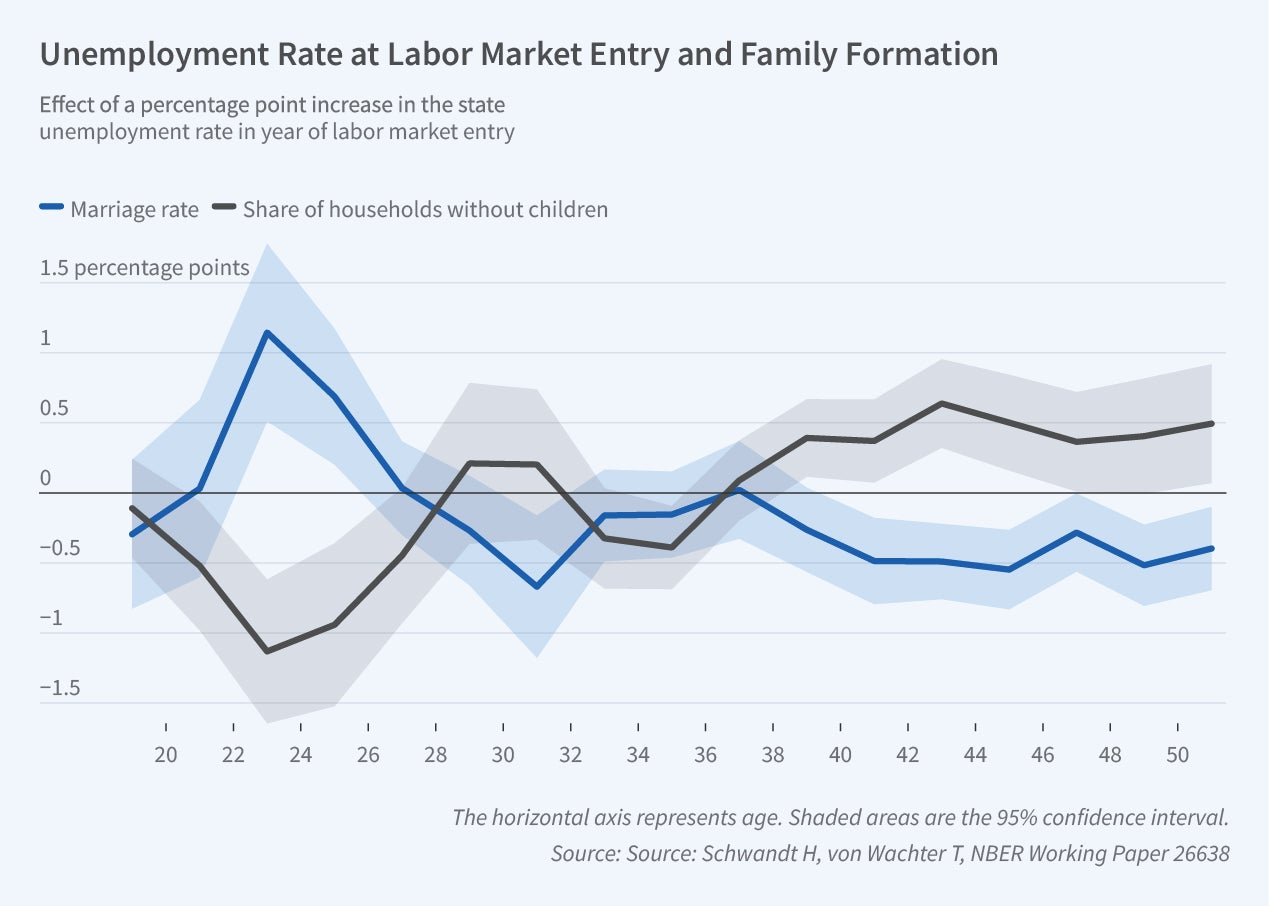

Our third main finding is that entering the labor market during a recession has substantial dynamic effects on key economic outcomes over the life cycle, including annual earnings [Figure 3], but also wages, employment, poverty, and receipt of income from government programs. We find that despite initial earnings recovery in their mid-30s, adversely affected entry cohorts suffer a reduction in annual earnings and hourly wages as they reach their mid-40s. Our fourth main finding [Figure 4] is that recession-entry cohorts tend to marry and have children earlier, then experience a rise in divorce, and in the long run see lower marriage rates, higher divorce rates, and smaller family sizes.

Our fifth main finding is that those who enter the labor market during a downturn tend to be married to spouses with slightly less education, and who have similar long-run income losses [Figure 3] and increased disability risk from adverse entry.

Our sixth main finding is that compared to White recession graduates, non-White individuals experience larger initial economic losses and mortality increases that appear earlier — during the first decade after joining the labor market. Non-White individuals also do not experience a short-term increase in family formation, suggesting that the stronger negative income may offset lowered opportunity costs. Across genders, on the other hand, effect patterns are similar in the short and medium run. But in the long run, both female and non–White recession graduates increase their labor force participation while experiencing smaller income losses. At the same time, they suffer greater mortality increases due to heart, liver, and lung disease in the long term.

Life-Cycle Impacts of Recessions Occur in Three Phases

Our results imply that the life-cycle impacts of adverse labor market entry occur in three phases. Shortly after the end of the recession, when the economy and employment have returned to normal for most workers, we see persistent but declining earnings reductions as predicted by most career models. In this phase, a rise in family formation and fertility occurs, suggesting that fewer labor market opportunities may lead some young individuals to invest time in marriage and child-rearing. Mortality is not significantly affected, as most young people’s health is far from the threshold leading to mortality.

In the medium run, roughly when workers are in their 30s, careers have settled at a better level: two-thirds of the earnings gap has faded. However, a rise in divorces occurs, likely due to lower-quality initial matches and possible chronic marital stress from lower wages, and fertility is depressed. During this phase, lower health investments and other stressors likely increase the latent health gap between lucky and unlucky cohorts, but with only small impacts on mortality.

In a third phase, when individuals reach midlife, ages 40 to 50, average health has declined enough that the health gap of unlucky graduates triggers increased mortality. At the same time, poorer health tends to further depress remarriage rates and earnings. Wages may start declining for healthy individuals as well, possibly because their slow start may have put them on the lower rungs of job or skill ladders. At the same time, these lower wages lead women and non-White individuals to increase their labor supply to make up for lost earnings. This chronic labor market stress might further depress marriage rates and harm health.

Implications for Social Insurance and Young Workers

Our findings cast new light on the ability of individuals to self-insure against temporary macroeconomic shocks early in their careers, as well as the role of public social insurance programs. Our results suggest that unlucky labor market entrants have some ability to recover their earnings losses through higher labor supply, but that this ability is limited by several factors. On average, only those not already working full time — notably women or non-White individuals who have lower mean employment rates in the cohort we study — can substantially offset losses through increased work. Yet even then the earnings gap is only closed temporarily, and initial and late-life earnings losses are never recovered. Furthermore, we find that this increased labor supply may come at a cost in terms of health.

More generally, the fact that an early shock has a comprehensive effect on economic, family, and health outcomes may mean it is hard to avoid these impacts without affecting some other dimension of lifetime outcomes. Our finding that unlucky individuals marry unlucky spouses within their cohort implies that within-family insurance may not be as effective in offsetting the effect of a weak labor market as it may be for buffering the effect of an individual job loss.

These findings put a spotlight on public social insurance mechanisms and the role of government interventions during recessions. Government programs targeted at lower-income people play some role in buffering these losses, mostly initially, but are unable to prevent long-lasting losses.6 Currently, only Social Security benefits and the progressive nature of income taxation are likely to help buffer some of the cross-cohort earnings variation due to recessions. New government programs keeping young people in education or employed could help to improve career outcomes and to prevent the potentially destabilizing impacts of anticipated family formation. Similarly, workers are only indirectly and imperfectly insured against adverse life-cycle effects on health. The increase in take-up of Social Security Disability Insurance benefits we find reflects one mechanism providing partial insurance. General health insurance such as Medicare or public funding of unpaid emergency room care could be another.

Our results imply that despite some available social insurance mechanisms, recessions lead to longer lasting and broader impacts on young workers than previously thought. This implies that monetary and fiscal policies aimed at avoiding or dampening downturns can play an important role in averting the long-term effects of adverse labor market entry.

Endnotes

"Socioeconomic Decline and Death: Midlife Impacts of Graduating in a Recession," Schwandt H and von Wachter T, NBER Working Paper 26638, January 2020; “Who Suffers during Recessions?” Hoynes H, Miller D, Schaller J. Journal of Economic Perspectives 26(3), Summer 2012, pp. 27–48.

“The Persistent Effects of Initial Labor Market Conditions for Young Adults and their Sources,” von Wachter T, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 34(4), 2020, pp. 168–194. “The Long-Term Labor Market Consequences of Graduating from College in a Bad Economy,” Kahn L. Labour Economics 17(2), 2010, pp. 303–316; “Initial Labor Market Conditions and Long-Term Outcomes for Economists,” Oyer P. Journal of Economic Perspectives 20(3), Summer 2006, pp. 143–160; “The Short- and Long-Term Career Effects of Graduating in a Recession,” Oreopoulos P, von Wachter T, Heisz A. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 4(1), January 2012, pp. 1–29; “Unlucky Cohorts: Estimating the Long-Term Effects of Entering the Labor Market in a Recession in Large Cross-Sectional Data Sets,” Schwandt H, von Wachter T. Journal of Labor Economics 37(S1), January 2019, pp. S161–S198; “The Lost Generation? Labor Market Outcomes for Post-Great Recession Entrants,” Rothstein J. Journal of Human Resources, online June 2021.

“Do Youth Employment Programs Work? Evidence from the New Deal,” Aizer A, Eli S, Lleras-Muney A, Lee K. NBER Working Paper 27103, July 2020.

“The Health Effects of Leaving School in a Bad Economy,” Maclean J. Journal of Health Economics 32(5), September 2013, pp. 951–964; “Economic Conditions and Mortality: Evidence from 200 Years of Data,” Cutler D, Huang W, Lleras-Muney A. NBER Working Paper 22690, September 2016.

“Unlucky Cohorts: Estimating the Long-Term Effects of Entering the Labor Market in a Recession in Large Cross-Sectional Data Sets,” Schwandt H, von Wachter T. Journal of Labor Economics 37(S1), January 2019, pp. S161–S198.

We find that SNAP and family welfare benefits (Aid to Families with Dependent Children and then Temporary Assistance for Needy Families) are initially elevated for non-White and lower-educated categories. However, these increases are not sufficient to offset a substantial decline in family income and a rise in poverty, or to prevent longer-term economic losses. The fact that the receipt of SNAP benefits among unlucky cohorts starts to increase again in middle age is a sign of social insurance at work.