International Tax Avoidance by Multinational Firms

A body of work documents profit-shifting behavior by multinational corporations. According to recent estimates, close to 40 percent of multinational profits — profits booked by firms outside of their headquarters’ country — are shifted to tax havens.1 US multinational companies appear to book a particularly large fraction of their foreign income in low-tax places.2

This phenomenon has attracted attention from economists and policymakers. In 2015, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the G20 launched the Inclusive Framework on Base Erosion and Profit Shifting, with the goal of curbing tax avoidance possibilities stemming from mismatches between different countries’ tax systems. In 2017, the United States reduced its corporate tax rate from 35 percent to 21 percent and introduced provisions to limit the erosion of the US tax base and tax some of the earnings booked by US multinationals abroad.

Recent research, however, suggests that these policies have so far made only a relatively small dent in profit shifting. More ambitious action — such as a coordinated minimum corporate income tax, to which more than 140 countries and territories committed in October 2021 — could reduce corporate profit shifting more significantly.

What Is the Scale of Global Profit Shifting?

Until recently, it was difficult to quantify global profit shifting due to a lack of data on the location of corporations’ profits. Companies are generally not required to publish their profits and tax payments on a country-by-country basis.

Thomas R. Tørsløv, Ludvig S. Wier, and I attempt to address this gap by leveraging macroeconomic data known as foreign affiliates statistics.3 These data record, among other information, the value added, wages, and profits of foreign firms — defined as firms more than 50 percent owned by foreign shareholders — in each country, including in the main tax havens. These are typically subsidiaries of foreign multinationals.

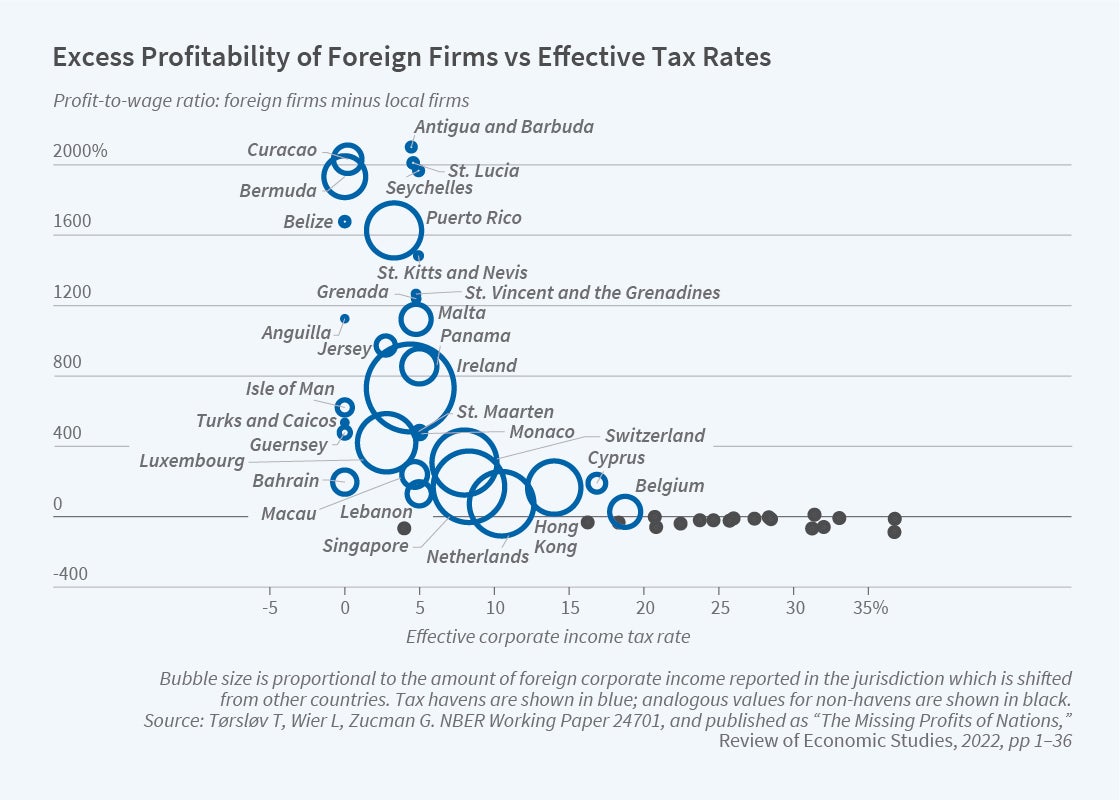

Using these data, we propose a simple method to infer profit shifting. By combining foreign affiliates statistics with national accounts data that cover foreign and local firms incorporated in each country, we estimate the profitability of foreign versus local firms in tax havens. Foreign firms turn out to be much more profitable than local firms in these territories. The ratio of pretax profits to wages is around 30 to 40 percent for local firms, but it is an order of magnitude larger for foreign firms — as high as 800 percent in Ireland. That is, for €1 of wages paid to Irish employees, foreign multinationals book €8 in pretax profits in Ireland, primarily reflecting profit shifting into the country.

Figure 1 shows that the excess profitability of foreign firms over local firms is specific to tax havens. The graph plots the difference between the profits-to-wages ratio of foreign and local firms against the country’s effective corporate income tax rate in 2015. Bubble sizes are proportional to the amount of profit which we estimate is shifted. In high-tax countries, foreign firms tend to be slightly less profitable than local firms, while in tax havens — shown in blue in the figure — foreign firms are abnormally profitable.

Leveraging this differential profitability, we estimate that 36 percent of multinational profits are shifted to tax havens globally. US multinationals appear to shift more than half of their multinational profits, compared with about a quarter of profits for corporations headquartered in other countries.

Did the Tax Cut and Jobs Act Reduce Profit Shifting by US Firms?

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, enacted at the end of 2017, dramatically changed the profit-shifting incentives of US corporations. The act lowered the US federal corporate income tax rate from 35 to 21 percent, reducing the gap between US and foreign rates. The US went from a worldwide tax system in which the foreign profits of US firms were, upon repatriation, subject to taxation in the United States, to a territorial tax system in which foreign profits are generally exempt from US taxes. The act also introduced three provisions to reduce incentives to shift profits to tax havens: a US tax on foreign income subject to low tax rates abroad; a reduced rate on foreign income derived from intangibles booked in the United States; and measures to limit the deductibility of certain payments that were suspected of being associated with strategies for shifting income out of the United States.

Javier Garcia-Bernardo, Petr Janský, and I study the effect of this reform on the international allocation of US firms’ profits.4 Has the amount of profit booked in tax havens declined? And if so, are more profits booked by US companies in the United States or in other relatively high-tax countries? To address these questions, we combine and reconcile the publicly available data on the location of US firms’ profits, including survey data from the US Bureau of Economic Analysis, balance of payments data, and the public financial statements of listed companies. Two main findings emerge.

First, consistent with incentives introduced in the law, US corporations booked a larger share of their profits in the United States after 2018 than before. This change, however, is relatively small: the share of profits booked domestically has increased by between 3 and 5 percentage points.

Second, the geographical allocation of the foreign profits of US multinationals does not appear to have been significantly affected by the act. The share of foreign profit booked in tax havens remained stable at around 50 percent between 2015 and 2020. Since the share of profits outside of the United States has only slightly declined — to about 27 percent for all US corporations — the share of total (domestic plus foreign) profits booked by US corporations in tax havens has remained between 13 and 15 percent, a historically high level, throughout the period [Figure 2].

This is not to say that the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act did not have any effect. Some firms changed their behavior, and in some cases the changes were dramatic. Six large listed companies — Alphabet, Microsoft, Facebook, Cisco, Qualcomm, and Nike — have decreased their declared foreign earnings by over 20 percentage points since 2018. A forensic analysis of these companies’ financial statements shows this decline to be related to changes in profit shifting, more precisely to repatriation of intellectual property to the United States. These large firms’ behaviors drive the macroeconomic decline in the share of US multinationals’ profit booked outside the United States.

Transfer-Pricing Regulation and Tax Planning Services

Under the leadership of the OECD, many countries have implemented standardized regulations that strengthen information reporting with a view to curbing profit shifting. Evaluating these regulations is difficult, both because their introduction is often gradual and because researchers lack access to the necessary data.

Sebastián Bustos, Dina Pomeranz, Juan Carlos Suárez Serrato, José Vila-Belda, and I attempt to overcome these limitations by evaluating the effect of the transfer-pricing regulations introduced by Chile in 2011.5 This reform expanded information reporting requirements on international transfers by multinationals, changed legislation to make it easier for the tax authority to enforce transfer-pricing rules, and increased resources devoted to the enforcement of these rules by the tax authority. It transformed Chile from a laggard to a leader in the implementation of OECD transfer-pricing standards.

Chile is a good laboratory to study the effect of transfer-pricing regulations because the Chilean authorities maintain detailed, high-quality administrative corporate tax data and customs data, which we were able to access for our analysis.

Our results suggest that the reform did not significantly reduce profit shifting. The propensity of multinationals to make tax-motivated payments to their foreign affiliates for intellectual property, interests, or services did not change. There is no evidence that the reform affected the prices of goods traded internally by multinational companies. Consistent with these results, corporate tax payments do not appear to have increased.

To better understand these results, we complement our quantitative analysis with in-depth interviews with transfer-pricing experts, including tax advisers from consulting firms and in-house accountants. These interviews reveal that the Chilean reform led to a surge in the demand for tax advisory services to comply with the new regulations. Providers of tax advisory services upsold clients additional tax planning services, leading to a boom in the employment of transfer-pricing experts in Chile. These results suggest that taking into account the supply of tax planning services is important for understanding the dynamic of tax compliance in general, and profit shifting in particular.

Changes Ahead?

Although recent policy initiatives do not appear to have had large effects on profit shifting, reforms that are currently being discussed may have more substantial effects. In October 2021, more than 140 countries and territories agreed to implement a minimum corporate income tax of 15 percent. Such an agreement — details of which are still being finalized — would mark a milestone because it would be the first international agreement constraining tax rates. Since the end of the 1990s, high-income countries have signed agreements to harmonize their corporate tax bases, but these agreements are silent regarding tax rates.

If well implemented, a minimum tax of this kind would remove incentives for countries to offer rates lower than 15 percent since these low rates would be offset by additional taxes owed in other countries, such as the headquarter country of a multinational company. This would reduce the incentive for firms to shift profits across national borders.

Some observers have noted that the proposed 15 percent rate is lower than what working-class and middle-class households typically pay in taxes in high-income countries. It is also lower than the average statutory rate that corporations face in those places. There is a chance that such a low reference point might trigger an additional reduction in statutory corporate tax rates, potentially reinforcing the race to the bottom with corporate taxation observed since the 1980s. Moreover, the agreement includes carveouts allowing corporations with sufficient activity in low-tax countries to be exempt from the minimum tax.

In an EU Tax Observatory report, Mona Barake, Paul-Emmanuel Chouc, Theresa Neef, and I show that the revenue potential of a minimum tax is large, but that revenues depend crucially on the rate chosen and on whether substantive carveouts are allowed.6 In the United States, the European Union, and the main developing countries combined, a 25 percent minimum tax without carveouts could generate $575 billion per year in additional corporate income tax revenues — about four times as much as the current 15 percent agreement.

About the Author(s)

Footnotes

“The Missing Profits of Nations,” Tørsløv T, Wier L, Zucman G. NBER Working Paper 24701, revised April 2020. Forthcoming in Review of Economic Studies.

“The Exorbitant Tax Privilege,” Wright T, Zucman G. NBER Working Paper 24983, September 2018.

“The Missing Profits of Nations, Tørsløv T, Wier L, Zucman G. NBER Working Paper 24701, revised April 2020. Forthcoming in Review of Economic Studies.

“Did the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act Reduce Profit Shifting by US Multinational Companies?” Garcia-Bernardo J, Janský P, Zucman G. NBER Working Paper 30086, May 2022.

“The Race between Tax Enforcement and Tax Planning: Evidence from a Natural Experiment in Chile,” Bustos S, Pomeranz D, Suárez Serrato JC, Vila-Belda J, Zucman G. NBER Working Paper 30114, June 2022.

“Collecting the Tax Deficit of Multinational Companies: Simulations for the European Union,” Barake M, Neef T, Chouc PE, Zucman G. EU Tax Observatory Report 1, January 2021.