Journey across a Century of Women

My talk will take us on a Journey across a Century of Women — a 120-year odyssey of generations of college-graduate women from a time when they were only able to have either a family or a career (sometimes a job), to now, when they anticipate having both a family and a career. More women than ever before are within striking distance of these goals.

Fully 45 percent of young American women today will eventually have a BA degree, and more than 20 percent of them will obtain an advanced degree above an MA. More than 80 percent of 45-year-old college-graduate women have children, either biological or adopted. More women than men graduate from college, and there is greater similarity in their ambitions and achievements than ever before. This should all make for a very pleasant ending to the journey. But that happy ending doesn’t seem to be happening. A few clarifications: my evidence concerns the United States and the history of its college-graduate men and women. I will focus on college-graduate women because they have the greatest opportunities to achieve “career.” Career is achieved over time, as the etymology of the word — meaning to run a race — would imply. A career generally involves advancement and persistence and is a long-lasting, sought-after employment, the type of work — writer, teacher, doctor, accountant, religious leader — which often shapes one’s identity. A career needn’t begin right after the highest educational degree; it can emerge later in life. A career is different from a job. Jobs generally do not become part of one’s identity or life’s purpose. They are often solely taken for generating income and generally do not have a clear set of milestones.

I recently finished most of a book on this century-long journey. But my book, like the Old Testament, was written in a BCE world — in this case, Before the Corona Era. Many inequities have been exposed by the COVID-19 economy and society, most notably those concerning social justice and our criminal justice system. The COVID economy has also magnified gender differences at work and in the home. Women are essential workers, but cannot be that at home and at work simultaneously. The burden of school closings on working parents that will continue into the coming year could erase years of career gains by young women in a way we have rarely seen. That is where my talk will take us. But first, we must journey to the beginning. I’ll begin the journey 120 years ago, when college-graduate women were faced with the stark choice of family or career (sometimes a job).

Five distinct groups of women can be discerned across the past 120 years, according to their changing aspirations and achievements. Group One graduated from college between 1900 and 1919 and achieved “Career or Family.” Group Two was a transition generation between Group One, which had few children, and Group Three, which had many. It achieved “Job then Family.” Group Three, the subject of Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique, graduated from college between 1946 and 1965 and achieved “Family then Job.” Group Four, my generation, graduated between 1966 and 1979 and attempted “Career then Family.” Group Five continues to today and desires “Career and Family.”

College-graduate women in Group One aspired to “Family or Career.” Few managed both. In fact, they split into two groups: 50 percent never bore a child, 32 percent never married. In the portion of Group One that had a family, just a small fraction ever worked for pay. More Group Two college women aspired to careers, but the Great Depression intervened, and this transitional generation got a job then family instead. As America was swept away in a tide of early marriages and a subsequent baby boom, Group Three college women shifted to planning for a family then a job. Just 9 percent of the group never married, and 18 percent never bore a child. Even though their labor force participation rates were low when they were young, they rose greatly — to 73 percent — when they and their children were older. But by the time these women entered the workplace, it was too late for them to develop their jobs into full-fledged careers.

“Career then Family” became a goal for many in Group Four. This group, aided by the Pill, delayed marriage and children to obtain more education and a promising professional trajectory. Consequently, the group had high employment rates when young. But the delay in having children led 27 percent to never have children. Now, for Group Five the goal is career and family, and although they are delaying marriage and childbirth even more than Group Four, just 21 percent don’t have children.

You may be thinking that, because of large increases in college graduation, most of the differences across the groups concern selection into who goes to and graduates from college. The surprising finding is that selection is not that important. I’ve tracked college entrance classes from the 1890s to the 1990s of women who have similar ability and parental resources. Their marriage ages and birth fractions track those of the total college- graduate group astoundingly well. Treatment, not selection, dominates.

College for Group One had a treatment effect by enabling women to be financially independent — they didn’t have to marry. After Group One, as women’s potential earnings rose and as substitutes for household goods became cheaper, husbands’ preferences, rather than necessarily changing, became more expensive. Though family came first for Group Three, college women planned their home confinement and their eventual escape. They trained to be teachers, nurses, social workers, librarians, and administrators after the kids were sufficiently grown. For Group Four, the Pill and its dissemination to young, single women enabled the delay of marriage and family and helped boost their investment in a career. But the biological clock ran out for many of these women. Group Five has pushed back marriage and family even further, but birth rates have risen, in part due to assisted reproductive technologies that have enabled this group to “beat the clock.”

The transition wasn’t swift and it wasn’t due mainly to dissent. Instead, it was often due to technological advances, increased earnings, and greater education.

Aspirations and achievements of college women greatly changed across the past century, with increased income, the mechanization of the household, and technological improvements in fertility control and assisted reproductive methods. But the structure of work and the persistence of social norms, no matter how much weaker they have become, have limited the success of college-graduate women in achieving career and family.

An important accompaniment to the transition across the Groups concerns changes in customs and norms. For the past 50 years, the General Social Survey has asked respondents whether they agree more or less strongly with the statement: “Preschool children are likely to suffer if their mother works.” The responses are depicted by the respondents’ birth years. As can be seen, agreement is always less for women than for men, and decreases for both men and women by birth cohort. It also increases with age, since earlier birth cohorts were generally older when interviewed than more recent birth cohorts. Norms became more expensive to sustain, and they changed. At the same time that the cost of not working rose, childcare became more available, more commonly used, and generally more acceptable.

To measure the degree of success at achieving both career and family that women in these groups achieved, I created definitions. Family means having a child, biological or adopted, but not necessarily a husband or partner. (Sorry, dogs do not count as surrogate children). Career is achieved by exceeding a level of income for three years in each five-year period where the income level is given by the income of a man of the same age and education at the 25th percentile of the male distribution. Several longitudinal datasets are used, namely the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (1979) and the Health and Retirement Study (HRS) linked to Social Security and tax data.

Interestingly, success at career and family for women increased both across and within cohorts. The success rate for women in their mid-50s is around 30 percent — half that for men — for the latest group that can be observed until that age. This is the group born between 1958 and 1965. But the success rate for that birth group of women was just 22 percent when they were in their late 30s, or 40 percent of the success rate for comparable men.

Even though a succession of women, group after group, advanced on this journey, women’s careers still often take a back seat to those of their husbands. The most recent group has expressed its disappointments and frustrations by focusing on issues such as bias, pay inequity, salary transparency, and sexual harassment.

But as each group progressed and passed the baton to the next, and as actual barriers fell and social norms changed, the real underlying problem that fuels differences in occupations, promotions, and pay has been revealed. Unquestionably, classic discrimination, bad actors, sexual harassment, and biased workers and supervisors exist. But most of the difference is due to something else.

To paraphrase Betty Friedan, the new “problem with no name” is the notion of Greedy Work — that there are large nonlinearities and convexities in pay. To have a family takes the time of at least one parent. There is no way to contract out all childcare, and one wouldn’t want to do that, or why have children in the first place? Parents have children to spend time with them. For college graduates, the gender gap in earnings is an indication and a symptom of career blockage.

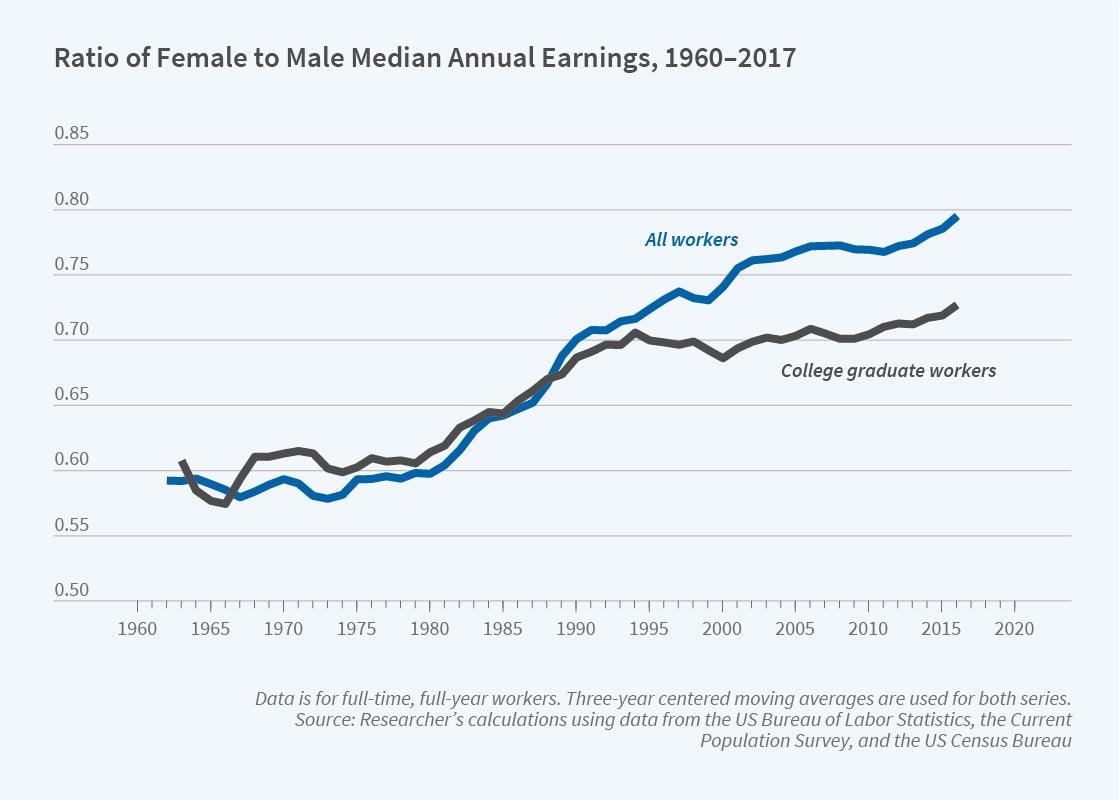

Women earn less than men, on average. The ratio of women’s earnings to men’s, often adjusted by hours of work, is referred to as the gender earnings gap, since it is often given as the log of the ratio. The ratio for all workers narrowed considerably from the early 1960s until today, but is still around 0.8. That for college-graduate women to college-graduate men followed a similar path until the late 1980s, when it flattened out. Some of the clues as to why the ratio is still substantial and why the ratio for college-graduate women to men became smaller than for the aggregate after the late 1980s are:

- The gender gap in earnings exists for both annual earnings and those on an hourly basis, so it is not just due to the fact that women work fewer hours.

- Women with children earn less than women without children.

- Earnings gaps increase with age up to a point, and they increase with joyous events like births and, often, marriage.

- Gaps are greater at the upper end of male earnings and education levels.

- The more unequal earnings are for an occupation, the lower are women’s earnings relative to men’s.

- The gender earnings gap is greater in occupations that have more demands on employee time and where face time and client relationships matter most.

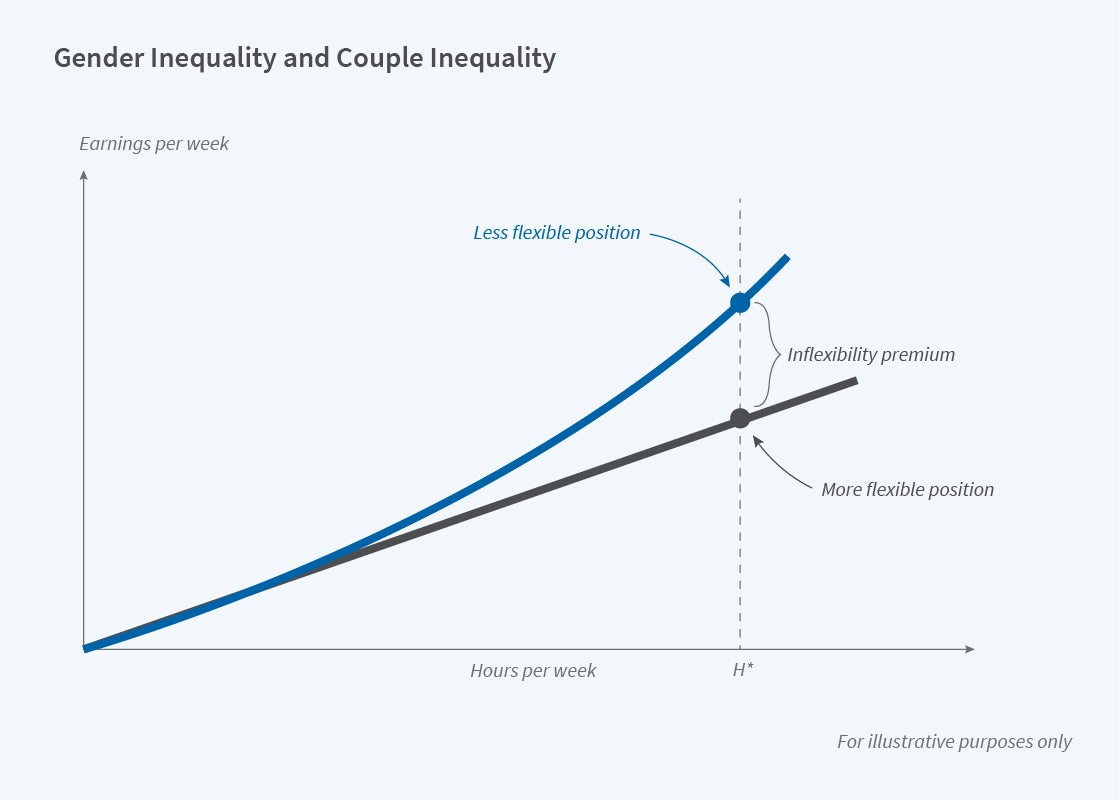

The flip side to gender inequality is couple inequity. Working mothers are on-call at home whereas working fathers are on-call at work. The reasons for both gender inequality and couple inequity are the same. The issues are the two sides of the problem mentioned above.

Many jobs, especially the higher-earning ones, pay far more on an hourly basis when the work is long, on-call, rush, evening, weekend, and unpredictable. And these time commitments interfere with family responsibilities. The problem is illustrated here.

One job (the gray line) is flexible and has a constant wage with respect to hours. The other job (blue line) is not so flexible and has a wage rate — the slope of the earnings curve — that rises with hours. A couple with children can’t both work at the blue dot. They could both work at the gray dot. But if they did, they would be leaving a lot of money on the table: for each of them it is given by the distance between the two dots. So one works the flexible, less remunerative job and the other works the less flexible, more remunerative job. More often than not, the man takes the less flexible, higher-paying job.

For many highly educated couples with children, she’s a professional who is also on-call at home. He’s a professional who is also on-call at the office. In consequence, he earns more than she does. That gives rise to a gender gap in earnings. It also produces couple inequity. If the flexible job were more productive, the difference would be smaller, and family equity would be cheaper to purchase. Couples would acquire it and reduce both the family and the aggregate gender gap. They would also enhance couple equity.

Note that even if these were same-sex couples, there could still be couple inequity without gender inequality. And even if couples wanted a 50-50 relationship, high earnings for the position that had less-controllable hours could entice them to engage in a new version of an old division of household labor.

What are the solutions? First off, any solution must involve lowering the cost of the amenity — temporal flexibility. The simplest is to create good substitutes. Clients could be handed off with no loss of information. Successfully deployed IT could be used to pass information with little loss in fidelity. Teams of substitutes, not teams of complements, could be created, as they have been in pediatrics, anesthesiology, veterinary medicine, personal banking, trust and estate law, software engineering, and primary care. The cheaper the amenity, the more linear total pay becomes by hours worked.

But the tale I have been telling has been set in a BCE world. In mid-March 2020, suddenly and swiftly, we descended into a DC (During Corona) world. Most workers sheltered in place and worked from home. Fortunate children had online schooling and at-home help. Less fortunate workers were deemed essential and often worked in unhealthful circumstances. Less fortunate children lost valuable schooling.

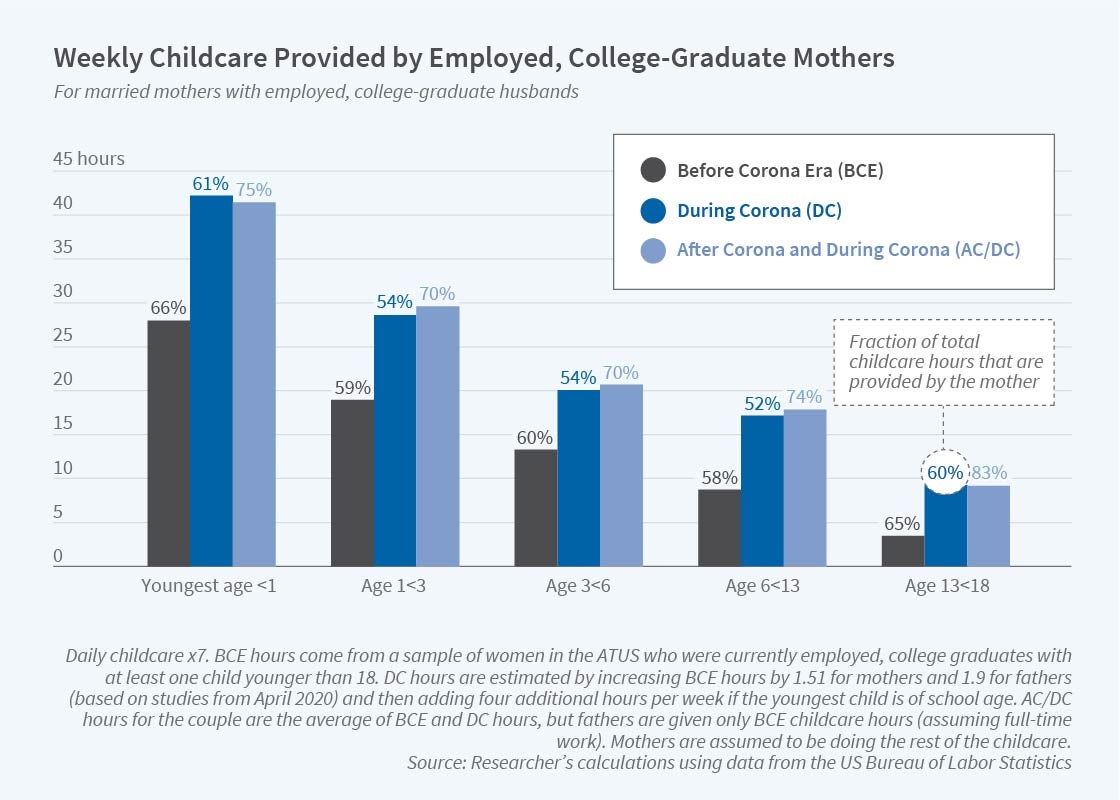

How does our understanding of the BCE world of career and family help us understand the impact of the new DC era, and what will come after? I will focus on college-graduate, employed adults and their families. These parents and their children are clearly in the more fortunate category. I use the American Time Use Survey (ATUS) from 2010 to 2019 to compute child-care hours of mothers and fathers by the age of their youngest child.

The child-care hours of the mothers in the BCE world are given by the dark gray bars, and the fraction of the total parental child-care hours is given above the bars. In the BCE world, college-graduate employed mothers with college-graduate employed husbands and school-aged children were working around 60 percent of total child-care hours. That fraction was higher for mothers with the youngest children and lowest for those with the oldest children.

The descent into the DC world almost doubled total child-care hours for working couples with children. The dark blue bars denote the hours that mothers contributed to child care and are derived from various surveys done in the United States and elsewhere in April 2020, together with many assumptions. (The ATUS was not administered in March and April 2020, and although it was restarted in May, those numbers won’t be available for some time.)

In mid-March 2020, almost 90 percent of school-aged children were not physically in a school, and most child-care facilities for younger children were shuttered. Many families temporarily furloughed care workers who had worked in their homes. That greatly increased the child-care demands on mothers. But there was also more parental sharing, since many households had both parents at home full time. Consequently, the fraction of child care performed by women fell, even as the absolute number of hours greatly increased. For those with sick relatives, other care hours also increased, and for single mothers, care hours must have been overwhelming.

We are now moving to an entirely new AC/DC (After Corona/During Corona) world. Draconian pandemic restrictions have been partially lifted in some schools and daycare facilities. Daycare centers opened in most states by the early summer. There will probably be full-time in-place schooling in smaller school districts, part-time schooling together with part-time virtual at-home schooling in most of the larger, urban districts, and entirely virtual at-home schooling in other districts.

But full-time work has returned to many offices, stores, workplaces, construction sites, factories, and elsewhere. What can we expect to happen to the child-care and home-schooling burdens placed on parents? For most mothers, the AC/DC world will be the BCE world on steroids.

Here, I must go even further out on a data limb since, even though the first day of school is imminent as I am writing this, districts are still debating what they will do. One possible scenario is that in the AC/DC world, total child-care and home-schooling hours will be halfway between what existed in the BCE and DC worlds. That makes sense if schools and child care are available half the week. But because of nonlinearities in work, one member of the couple will go back to work full time and the other will work part-time from home and take care of the kids whenever in-person school is out and virtual school is in.

If history is any guide, men will go back to work full time and revert to their BCE childcare levels. Women will take up the slack and do a greater share of the total.

The bottom line may be that there will be no net gains for working women in the AC/DC world. What they gain from minimal school and daycare openings, they lose from less parental help at home. Because of convex hourly pay, couple equity remains expensive for the family unit. That expense persists from the BCE world, and the careers of many young women will take a back seat on this journey.

The corrective in the BCE world was to change the workplace by driving down the price of flexibility. The corrective in the AC/DC world must change the care place by driving down the cost of child care and other family demands. But how can one do that safely and equitably?

When public and free elementary schools spread in the United States in the 19th century, and when they expanded during the high school movement of the early 20th century, a coordinated equilibrium was provided by good governments. Good government today could do the same thing. We need to find safe ways to have classes for children — for their futures and for their parents’.

As in the Great Depression, we have unemployed labor. Today, many of the unemployed are highly educated recent college graduates and gap-year college students with little to do. They could be harnessed in a new Works Progress Administration manner and put to work educating children, especially those from lower-income families. They could free parents, especially women, to return to work. I’ll repurpose a name and call them the “Civilian College Corps” — a new CCC.

Some of the Corps’ educational work could be done remotely. The Corps could support beleaguered parents too exhausted to correct their children’s essays and too confused to help their children with algebra. Other Corps members could be in the classroom, helping districts cope with having fewer teachers because some older teachers don’t want to return to a school building. The Corps could employ those without jobs, meaning, and direction and give them something worthy to do: educate the next generation and help women go back to work full time, either in their homes or on-site.

In the BCE world, if the cost of flexibility were much lower, we would solve the problem of Greedy Work and achieve both gender equality and couple equity. In the AC/DC world, we must also reduce the cost to parents of educating and caring for children of all ages. The original journey was from career or family to career and family. The Journey continues.