Program Report: Public Economics, 2020

Public economics is the study of government intervention in the market economy, designed to move outcomes away from the market equilibrium. The two primary motivations for such interventions are improving market efficiency and redistributing resources across populations. The field is principally concerned with analyzing the effects of various tools — such as tax policies and social insurance programs — that are designed to achieve these aims.

The NBER Public Economics Program has made significant progress in understanding these issues during the eight years since the last program report. Between January 1, 2012 and the present — the time period covered by the current report — there were almost 2,000 NBER working papers in public economics. Much of this work has been fueled by the availability of new data sources that permit researchers to study longstanding questions with unprecedented precision and granularity.

Rather than attempting to summarize this entire corpus of work, this report focuses on two areas of research: Determinants of the take-up of government programs and the impacts of these programs on behavior and economic outcomes. These examples are not meant to be exhaustive; they focus on a limited, and admittedly somewhat arbitrary, subset of the exciting research being undertaken by program affiliates. However, they illustrate some of the main themes and richness in analysis that have emerged from recent work. All of the recent working papers by program affiliates may be found here.

Take-up and Targeting of Government Programs

A natural assumption when designing government programs — one made in much of the theoretical literature in public finance for decades — is that everyone who is eligible for the program in question participates. But enrollment in social safety net programs is typically not automatic: individuals must apply for the programs and demonstrate eligibility. Often, eligibility rules are complicated, application forms long, and documentation requirements substantial. Perhaps as a result, many people who are eligible for social safety net programs do not participate. Common hypotheses for this “incomplete take-up puzzle” include lack of information about eligibility, transaction costs associated with enrollment, and stigma associated with applying for or enrolling in the programs.

Recent research has examined two empirical questions that relate to take-up: identifying barriers to take-up and estimating how those barriers affect the characteristics of applicants and enrollment, known as the “targeting” property of the barrier. Economists have posited very different hypotheses for what kinds of eligible individuals are deterred from enrolling. Drawing on neoclassical theory, some have argued that those deterred might be the least needy among the eligible, while recent work in behavioral economics has suggested that deterrent ordeals may have exactly the opposite targeting effect, discouraging precisely those applicants the social planner would most like to enroll.

This ambiguity about whether targeting tends to exclude the most or the least needy potential beneficiaries has made empirical work on the topic all the more important. Much of this empirical work has been conducted in the form of randomized controlled trials of particular interventions, their impact on take-up, and the characteristics of those who take up, but there have also been important quasi-experimental papers. We summarize findings from selected papers in what follows.1

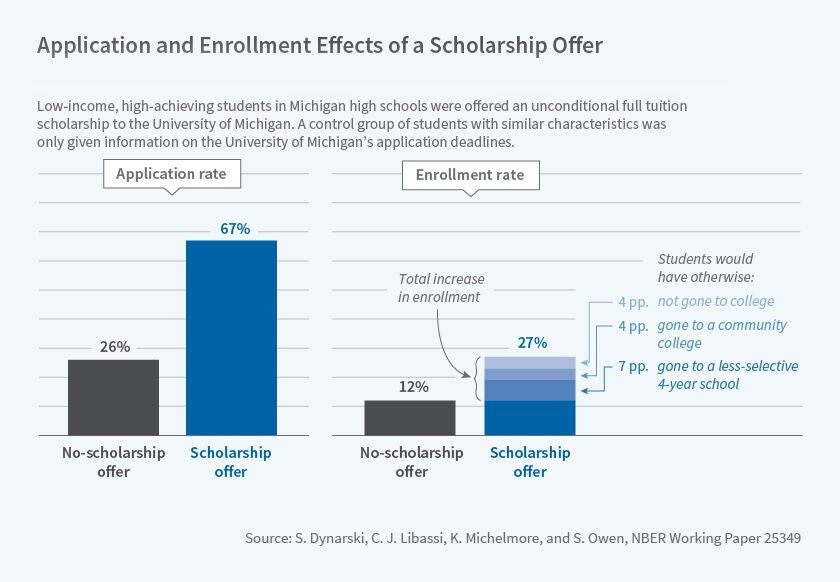

Reductions in informational barriers have been found to be quantitatively important in generating take-up in some contexts but not in others. In a recent series of randomized interventions aimed at increasing take-up of the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) among likely eligible individuals, Dayanand Manoli and co-authors have found that take-up is highly sensitive to both the frequency and nature of reminder letters sent by the Internal Revenue Service, although the effects of the reminder do not persist into the following year when the individuals would have to sign up again.2 Likewise, Susan Dynarski and collaborators find that an information intervention that informed high-achieving students about a tuition-free college scholarship increased enrollment at a flagship state university.3 There is also quasi-experimental evidence that information is an important barrier to take-up of post-secondary enrollment among unemployment insurance recipients.4 However, Hunt Allcott and Michael Greenstone find in a randomized evaluation of informational interventions that lack of awareness is not a contributor to low take-up of home energy efficiency audits.5

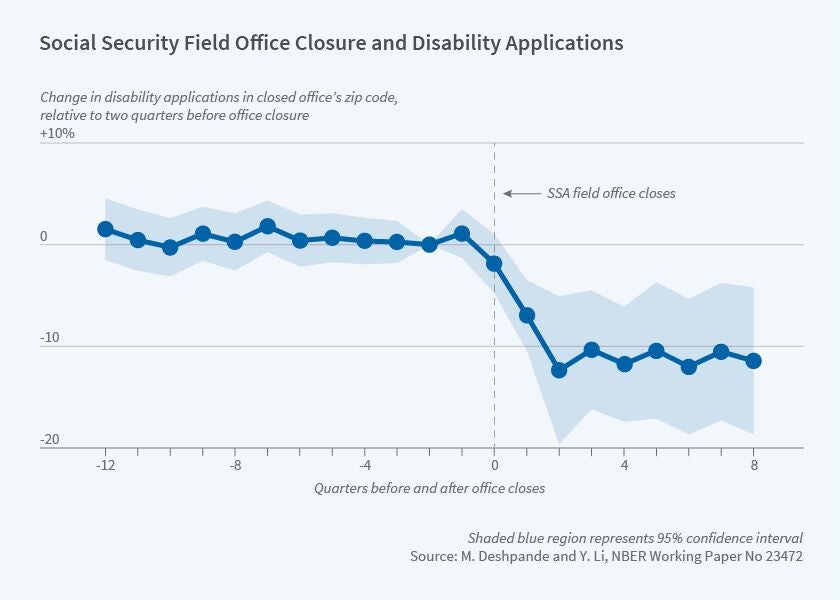

Reductions in transactional barriers have been found to be important for increasing enrollment in several different programs. Amy Finkelstein and Matthew Notowidigdo find that for elderly individuals eligible for the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), information alone can have an effect on take-up, but that pairing it with assistance doubles the impact.6 Manasi Deshpande and Yue Li find that the closing of local field offices where Social Security Disability Insurance and Supplemental Security Income applications can be submitted substantially reduces both applications and enrollment.7 Vivi Alatas and co-authors present evidence from a randomized evaluation across Indonesian villages that increasing the transaction cost of applying for a conditional cash transfer program reduces enrollment.8

In addition to investigating how barriers to enrollment affect take-up rates, recent research has focused on how these barriers may affect the characteristics of applicants and enrollees. From information interventions, there is evidence that complexity disproportionately deters EITC enrollment of lower-income potential recipients, and that, due at least in part to a lack of insurance literacy, some lower-income employees choose health insurance plans which, while more expensive than other options, do not offer any additional coverage.9 Information about eligibility disproportionately encourages enrollment among eligible, relatively higher socioeconomic status applicants in the SNAP program.10

Studies have found that making it more burdensome to access benefits — that is, imposing transaction costs — increases targeting on some but not all dimensions. Alatas et al. find that introducing transaction costs by requiring individuals to apply for a conditional cash transfer in Indonesian villages rather than have the government automatically screen the individuals for eligibility improves targeting; specifically, it results in enrolling substantially poorer people.11 However, marginally increasing the transaction costs does not further affect the characteristics of enrollees. Deshpande and Li find that increasing the transaction costs associated with US disability programs worsens targeting among applicants, as evidenced by an increase in the share of applicants with only moderately severe disabilities, but improves targeting among enrollees, as evidenced by a decrease in the share of enrollees with the least severe disabilities (conditional on being severe enough to be eligible).12 However, they also find that the increased transaction costs reduce the share of enrollees with low education levels and low pre-application earnings, suggesting a reduction in targeting. Finkelstein and Notowidigdo, in contrast, find that reducing transaction costs decreases targeting on all dimensions, and at all stages (application and enrollment).13

In summary, recent work has uncovered evidence not just of the importance of barriers to take-up in general, but on precisely how those barriers may vary across programs and subgroups. Although there are no universal lessons in terms of the determinants of take-up and targeting, these studies pave the way for further work that can be conducted by government agencies and practitioners to understand take-up in the context of the particular policy under consideration. The normative implications of different targeting properties are unclear and also remain an important and likely fruitful topic for further work.

Impacts of Government Programs and Tax Policies

Much as there has been great progress in understanding how take-up varies across government programs, the past eight years have seen tremendous progress in understanding program impacts. Much of this work has been fueled by the growing availability of population-level administrative tax data from the Department of the Treasury and the Census Bureau. Over these years, the Public Economics Program has fostered collaborative research between members of the group and members of government agencies such as the Office of Tax Analysis, the IRS, the Census Bureau, and others through an annual meeting on research using administrative tax data. Here, we summarize some examples of progress that has been made in understanding the causal effects of government programs using such data.

Several studies have analyzed how changes in tax incentives affect the behavior of individuals and corporations. For example, researchers have analyzed how local income and estate taxes affect the location of inventors, entrepreneurs, and wealthy individuals using modern administrative data sources. These studies have found that increases in top income tax rates and wealth taxes on the very wealthy induce significant migratory responses between states and even across countries.14 However, evidence on whether such tax increases induce “real” changes in aggregate business activity or innovation is more limited. Moreover, when inventors and entrepreneurs have strong ties to a research hub in a given area, their responsiveness to tax changes becomes much smaller.15

In a different vein, a series of studies have examined how affordable housing programs implemented by the government affect behavior and outcomes. Using methods ranging from randomized experiments to estimation of structural models, a series of studies have shown that there are large search frictions — a lack of information and support in the housing search process — that hamper low-income families’ ability to find affordable housing in neighborhoods that provide good opportunities for upward income mobility.16 Some well-designed affordable housing programs, in particular, those that provide customized search assistance, can be highly effective in helping families move to higher-opportunity neighborhoods. Focusing on a different program, Rebecca Diamond and Timothy McQuade show that the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit, a subsidy given to developers of affordable housing, revitalizes low-income neighborhoods by increasing property values and reducing crime rates, but has more negative effects in higher-income areas.17

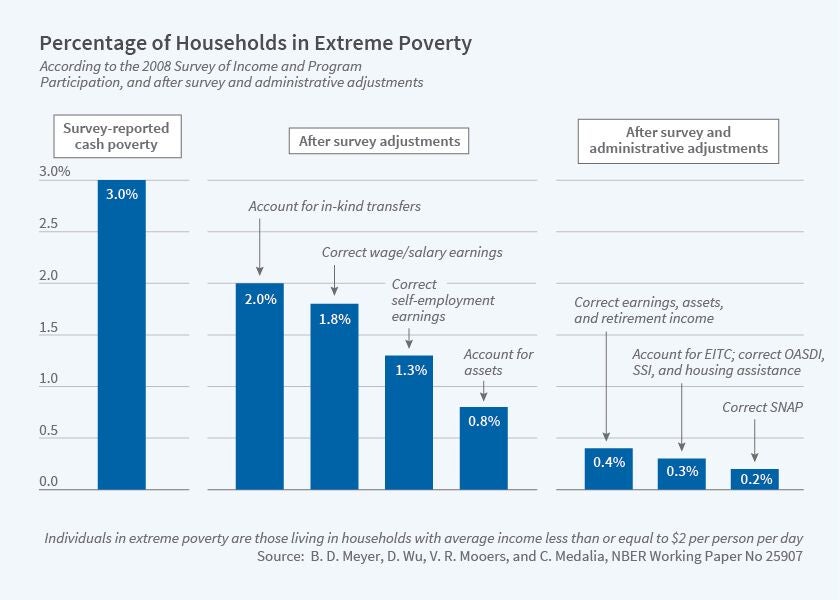

Finally, a third strand of research using administrative tax data has focused on improving measures of income, taking into account tax and transfer programs. Bruce Meyer and collaborators conducted a series of studies linking administrative data to survey data to show that surveys often understate income at the bottom of the income distribution because of underreporting of transfers, leading to an overstatement of the number of households living in extreme poverty.18 At the other end of the income distribution, recent studies have provided a more comprehensive picture of top income and wealth inequality, showing for instance that much of the wealth being accrued at the top comes from human capital rather than financial capital.19 Thomas Piketty, Emmanuel Saez, and Gabriel Zucman look across the entire income distribution and construct distributional national accounts that allocate GDP to income groups.20 These studies all examine income distributions at a single point in time. The growing availability of panel data has also enabled researchers to make progress in the measurement of income dynamics over time, documenting, for instance, that rates of intergenerational mobility vary sharply across geographic areas.21 These studies pave the way for further work understanding why income levels and mobility vary so sharply across areas and how government policies can influence mobility and growth.

No single unifying result about the causal effects of government programs emerges from these studies. Some tax policies induce large behavioral responses; others do not. In some cases, the same program has very different effects in different settings, depending upon how it is implemented.22

Perhaps the general lesson that public economists have learned in recent years is that there are important differences in the effect of public policies on households and firms. There may be no “one size fits all” answer to policy design questions. The context and specifics matter tremendously. Fortunately, the field is increasingly poised to tackle this richness and complexity, thanks to progress in data availability and empirical methods. This bodes well for the future of public economics, with much remaining to be discovered and the tools to do so now in hand.

Endnotes

“The Take Up of Social Benefits,” Currie J. NBER Working Paper 10488, May 2004, provides an overview of some of the earlier literature, while our review starts with working papers published in 2012.

“Psychological Frictions and the Incomplete Take-Up of Social Benefits: Evidence from an IRS Field Experiment,” Bhargava S, Manoli D. American Economic Review 105(11), November 2015, pp. 3489–3529; “Nudges and Learning: Evidence from Informational Interventions for Low-Income Taxpayers,” Manoli D, Turner N. NBER Working Paper 20718, November 2014, revised January 2016; “Reminders & Recidivism: Evidence from Tax Filing & EITC Participation among Low-Income Nonfilers,” Guyton J, Manoli D, Schafer B, Sebastiani M. NBER Working Paper 21904, January 2016.

“Closing the Gap: The Effect of a Targeted, Tuition-Free Promise on College Choices of High-Achieving, Low-Income Students,” Dynarski S, Libassi CJ, Michelmore K, Owen S. NBER Working Paper 25349, December 2018.

“A Letter and Encouragement: Does Information Increase Post-Secondary Enrollment of UI Recipients?” Barr A, Turner S. NBER Working Paper 23374, April 2017.

“Measuring the Welfare Effects of Residential Energy Efficiency Programs,” Allcott H, Greenstone M. NBER Working Paper 23386, May 2017.

Take-up and Targeting: Experimental Evidence from SNAP,” Finkelstein A, Notowidigdo MJ. NBER Working Paper 24652, May 2018.

“Who Is Screened Out? Application Costs and the Targeting of Disability Programs,” Deshpande M, Li Y. NBER Working Paper 23472, June 2017, revised October 2017.

“Ordeal Mechanisms in Targeting: Theory and Evidence from a Field Experiment in Indonesia,” Alatas V, Banerjee A, Hanna R, Olken BA, Purnamasari R, Wai-Poi M. NBER Working Paper 19127, June 2013.

“Psychological Frictions and the Incomplete Take-Up of Social Benefits: Evidence from an IRS Field Experiment,” Bhargava S, Manoli D. American Economic Review 105(11), November 2015, pp. 3489–3529; “Do Individuals Make Sensible Health Insurance Decisions? Evidence from a Menu with Dominated Options,” Bhargava S, Loewenstein G, Sydnor J. NBER Working Paper 21160, May 2015.

“Ordeal Mechanisms in Targeting: Theory and Evidence from a Field Experiment in Indonesia,” Alatas V, Banerjee A, Hanna R, Olken BA, Purnamasari R, Wai-Poi M. NBER Working Paper 19127, June 2013.

“Who Is Screened Out? Application Costs and the Targeting of Disability Programs,” Deshpande M, Li Y. NBER Working Paper 23472. June 2017, revised October 2017.

“Taxing Billionaires: Estate Taxes and the Geographical Location of the Ultra-Wealthy,” Moretti E, Wilson DJ. NBER Working Paper 26387, October 2019; “Behavioral Responses to State Income Taxation of High Earners: Evidence from California,” Rauh J, Shyu RJ. NBER Working Paper 26349, October 2019; “Taxation and the International Mobility of Inventors,” Akcigit U, Baslandze S, Stantcheva S. NBER Working Paper 21024, March 2015, revised October 2015.

“Taxation and Migration: Evidence and Policy Implications,” Kleven H, Landais C, Muñoz M, Stantcheva S. NBER Working Paper 25740, April 2019.

“Waiting for Affordable Housing in New York City,” Sieg H, Yoon C. NBER Working Paper 26015, June 2019; “Affordable Housing and City Welfare,” Favilukis J, Mabille P, Van Nieuwerburgh S. NBER Working Paper 25906, May 2019; “Creating Moves to Opportunity: Experimental Evidence on Barriers to Neighborhood Choice,” Bergman P, Chetty R, DeLuca S, Hendren N, Katz LF, Palmer C. NBER Working Paper 26164, August 2019.

“Who Wants Affordable Housing in their Backyard? An Equilibrium Analysis of Low Income Property Development,” Diamond R, McQuade T. NBER Working Paper 22204, April 2016.

“The Use and Misuse of Income Data and Extreme Poverty in the United States,” Meyer BD, Wu D, Mooers VR, Medalia C. NBER Working Paper 25907, May 2019.

“Capitalists in the Twenty-First Century,” Smith M, Yagan D, Zidar OM, Zwick E. NBER Working Paper 25442, January 2019, revised June 2019.

“Distributional National Accounts: Methods and Estimates for the United States,” Piketty T, Saez E, Zucman G. NBER Working Paper 22945, December 2016.

“The Opportunity Atlas: Mapping the Childhood Roots of Social Mobility,” Chetty R, Friedman JN, Hendren N, Jones MR, Porter SR. NBER Working Paper 25147, October 2018, revised February 2020; “Intergenerational Mobility of Immigrants in the US Over Two Centuries,” Abramitzky R, Boustan LP, Jácome E, Pérez S. NBER Working Paper 26408, October 2019.

“Site Selection Bias in Program Evaluation,” Allcott H. NBER Working Paper 18373, September 2012, revised September 2014.