The Labor Market for Financial Misconduct

Financial advisers in the United States manage over $30 trillion in investible assets, and plan the financial futures of roughly half of U.S. households. At the same time, trust in the financial sector remains near all-time lows. The 2018 Edelman Trust Barometer ranks financial services as the least trusted sector by consumers, finding that only 54 percent of consumers "trust the financial services sector to do what is right."1 The distrust of finance is perhaps not surprising in the wake of the recent financial crisis and several high-profile scandals that have dominated financial news. While it is clear that some egregious fraud occurs in the financial services sector, it is less clear whether misconduct is limited to a few scandals or is a pervasive feature of the industry. Moreover, if misconduct is pervasive, why can it survive in the marketplace, and conversely, which mechanisms constrain it from enveloping the entire industry?

This summary describes our research, which is joint work with Mark Egan, on these questions. We start by describing how we measure misconduct among all registered financial advisers in the U.S. We then turn to the role of labor markets in constraining misconduct, documenting that while some firms penalize misconduct through a sharp increase in job separations, other firms are willing to hire these advisers, recycling the bad apples in the industry. We then discuss evidence that suggests this phenomenon arises because of "matching on misconduct," in which advisers with misconduct records match with firms which specialize in misconduct, and that the presence of uninformed consumers may be critical to maintaining this equilibrium. We find that similar forces may also explain gender discrimination in the labor market of financial advisers, leading to a "gender punishment gap." We conclude by discussing how academic research may help guide evidence-based policy.

Measuring Misconduct

We began our research program by documenting the extent of misconduct in the financial advisory industry2 . To study misconduct by financial advisers, we construct a panel database of the universe of financial advisers (about 1.2 million) registered in the United States from 2005 to 2015, representing approximately 10 percent of total employment of the finance and insurance sector. Our data, which we have made available to other researchers, come from the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority's (FINRA) BrokerCheck website. The data contain advisers' complete employment history. Because the industry is heavily regulated, data on adviser qualifications provide a granular view of job tasks and roles in the industry. Central to our analysis, FINRA requires financial advisers to formally disclose all customer complaints, disciplinary events, and financial matters, which we use to construct a measure of misconduct.

We find that financial adviser misconduct is broader than a few heavily publicized scandals. Roughly one in 10 financial advisers who work with clients on a regular basis have a past record of misconduct. Common misconduct allegations include misrepresentation, unauthorized trading, and outright fraud— all events that could be interpreted as a conscious decision of the adviser. Adviser misconduct results in substantial costs: In our sample, the median settlement paid to consumers is $40,000, and the mean is $550,000. These settlements cost the financial industry almost half a billion dollars per year. A substantial number of financial advisers are repeat offenders. Past offenders are five times more likely to engage in misconduct than otherwise comparable advisers in the same firm, at the same location, at the same point in time. The large presence of repeat offenders suggests that consumers could avoid a substantial amount of misconduct by avoiding advisers with misconduct records.

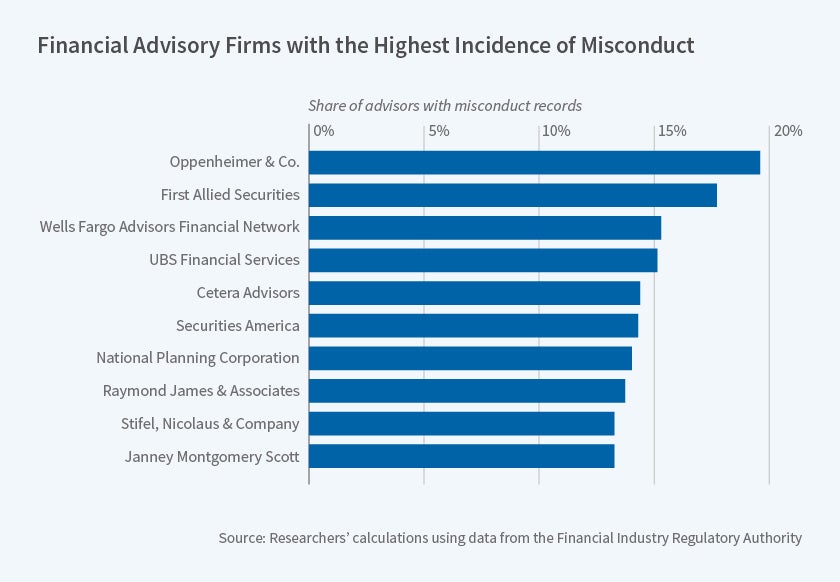

Moreover, misconduct is not randomly allocated across firms. We find large differences in misconduct across some of the largest and best-known financial advisory firms in the U.S. Figure 1 displays the top 10 firms with the highest share of advisers that have a record of misconduct. Almost one in five financial advisers at Oppenheimer & Co. had a record of misconduct. Conversely, at USAA Financial Advisors, the ratio was less than one in 36.

These simple statistics lead to two direct questions. First, given the presence of repeat offenders, why do market forces and regulators not drive these bad apples from the industry? Second, why can advisers and firms that consistently engage in misconduct coexist in the market with firms and advisers with clean records?

Labor Market Discipline

One would expect labor markets to discipline misconduct. In fact, one might expect that firms, wanting to protect their reputation for honest dealing, would fire advisers who engage in misconduct. Other firms would have the same reputation concerns and would not hire such advisers. In this scenario, advisers would be purged from the industry immediately following misconduct, and only advisers with a clean record would survive in equilibrium. Under this benchmark, punishment is extreme. There is an alternative scenario, however, in which misconduct is tolerated by firms. Firms do not fire advisers who engage in misconduct, and they tolerate a misconduct record in employing new advisers. In this case, tolerance of misconduct is extreme. Our results suggest that labor market behavior departs from these benchmarks in an interesting way: while some firms fire advisers who engage in misconduct, other firms hire these advisers, recycling bad apples in the market.

In fact, the average firm is relatively strict in disciplining misconduct. Following misconduct, roughly half of advisers do not keep their job in the subsequent year. The job turnover rate among advisers with recent misconduct is 48 percent per year— 29 percentage points higher than among advisers without recent misconduct. Firms account for the severity of misconduct when doling out punishments. Advisers whose misconduct results in higher monetary costs or those with more egregious misconduct such as fraud and forgery are more likely to lose their jobs following misconduct.

Although firms are strict in disciplining misconduct, the industry as a whole undoes some of the discipline by recycling advisers with past records of misconduct. Roughly half of advisers who lose a job after engaging in misconduct find new employment in the industry within a year. In total, roughly 75 percent of those advisers who engage in misconduct remain active and employed in the industry the following year. Industry reemployment helps explain why recidivism is so high, even though the average firm is strict in disciplining misconduct.

Critical to understanding the phenomenon of recycling bad apples is firm and employee "matching on misconduct." Advisers with past records of misconduct tend to move to firms whose current employees are more likely to be actively engaging in misconduct, and which punish misconduct less severely. The willingness to recycle advisers with past misconduct, and the "matching on misconduct," undermines discipline in the financial advisory industry.

Figure 1

Misconduct in Equilibrium: Why Does Misconduct Survive?

Why can firms that employ advisers who engage in misconduct survive in equilibrium with firms that do not engage in this activity? One would expect consumer demand to reflect the reputation for misconduct in the product market. Eugene Fama, in one paper, and Fama and Michael Jensen in another, argue that competition should lead to career punishments in labor markets.3 Then advisers who engage in misconduct and the firms that employ them, would not survive in the market for long. Which frictions prevent the market from achieving this outcome? This fact is even more puzzling when considering that the information on misconduct is publicly available.

We find evidence that the presence of unsophisticated consumers is one of the central frictions enabling misconduct. Even though misconduct records are public information, such unsophisticated customers do not know either that such disclosures exist, or how to interpret them. Differences in sophistication lead to market segmentation. Some firms "specialize" in misconduct and attract unsophisticated customers, and others cater to more sophisticated customers who recognize misconduct. We find evidence consistent with the idea that markets are segmented along dimensions of consumer sophistication. Misconduct is more common among financial advisers who deal with customers who are deemed less sophisticated by regulators. The type of compensation firms charge to clients is correlated with misconduct. Advisory firms that charge based either on assets under management or commissions tend to have higher rates of misconduct than firms that charge based on performance.

The geographic distribution of advisory firms is also consistent with market segmentation along the lines of investor sophistication. We find evidence that rates of misconduct are 19 percent higher, on average, in regions with the most vulnerable populations — those counties below the national averages in terms of household incomes and college education rates.

To summarize, unsophisticated consumers contribute to the existence and survival of firms that consistently engage in misconduct. By rehiring advisers with misconduct records, high-misconduct firms blunt the market discipline of low-misconduct firms.

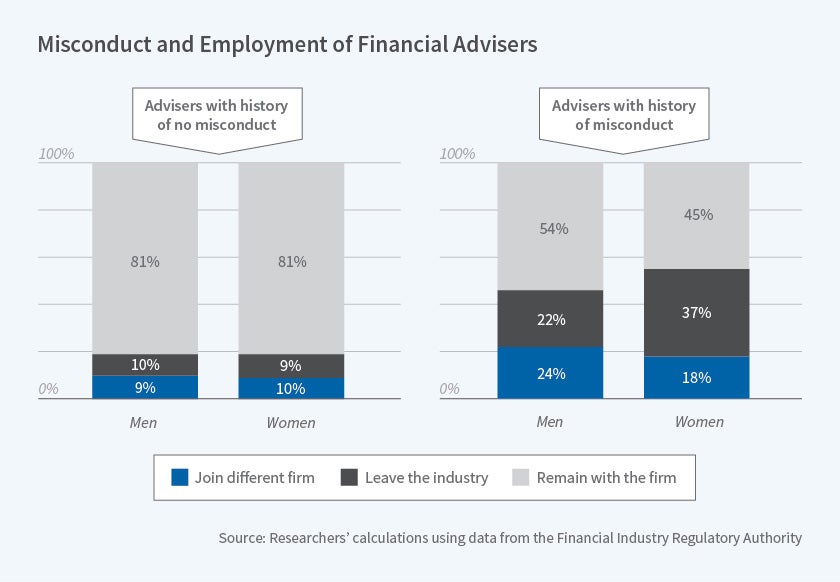

Figure 2

The Gender Punishment Gap

In addition to finding that the labor market for financial advisers recycles bad apples and results in matching on misconduct, we also find evidence of a "gender punishment gap."4 Following an incident of misconduct, female advisers are 9 percentage points more likely to lose their jobs than their male counterparts. Figure 2 [following page] displays job turnover in the financial advisory industry for male and female advisers with and without misconduct records. After engaging in misconduct, 54 percent of male advisers retain their jobs the following year while only 45 percent of female advisers retain their jobs, despite no differences in turnover rates for male and female advisers without misconduct records (19 percent). The gender punishment gap extends beyond the firm at which misconduct took place to other reemployment opportunities in the industry. While half of male advisers find new employment after losing their jobs following misconduct, only a third of female advisers find new employment.

We find no evidence that occupational segregation drives this gap. Because of the incredible richness of our regulatory data, we are able to compare the career outcomes of male and female advisers who are working at the same firm, in the same location, at the same point in time, and in the same job role. Differences in production, or the nature of misconduct, do not explain the gap. If anything, misconduct by female advisers is on average substantially less costly for firms.

The gender punishment gap increases in firms with a larger share of male managers at the firm and branch levels. For example, we find no evidence of a punishment gap at firms with an equal representation of men and women at the executive level. Conversely, at firms with no female representation at the executive level, women are 32 percentage points more likely to lose their jobs following misconduct than are their male counterparts. We extend our analysis to men with names that are relatively common in minority groups and find that the punishment gap and patterns of in-group tolerance extend to them as well. These results also suggest that the in-group tolerance we observe is not driven solely by gender-specific factors. In addition, we find no evidence that male minority managers decrease the gender punishment gap. In other words, managers only alleviate the punishment gap within their gender and ethnic group. This evidence is important because it rules out several potential alternatives, under which firms with female or minority male executives attract a pool of individuals with selected misconduct propensities. The gender punishment gap we identify is a potentially less salient form of discrimination that may limit the careers of women working in a high human capital, well-paid industry.

Our findings imply that too many female advisers with untarnished records are purged from the industry while too many fraudulent male advisers remain in the market, resulting in more misconduct. Gary Becker suggested that markets combat discrimination because discriminators are harmed with lower profits.5 However, misconduct-tolerant firms that have male advisers with records of misconduct can survive in equilibrium due to the presence of unsophisticated consumers. In other words, the product market equilibrium with unsophisticated consumers may make it easier to discriminate against female advisers.

Policy Response

Our results suggest that financial firms and regulators may want to pay close attention to "high-risk" financial advisers with misconduct records who are recycled across firms in the industry. Since our research findings were first circulated, there have been several policy initiatives in this direction. The Office of Compliance Inspections and Examinations with the Securities and Exchange Commission, the Massachusetts Securities Division, FINRA, and the Financial Stability Board have added hiring and employment of high-risk and recidivist brokers to their examination priorities.

Our work also suggests that unsophisticated consumers are essential to the survival of misconduct in this market. Increasing market transparency and providing consumers with access to more information could reduce the number of unsophisticated consumers. FINRA's promotion of its BrokerCheck website is a step in this direction. We have also constructed a new website (www.eganmatvosseru.com) to help raise awareness of adviser fraud and to provide resources for policymakers, practitioners, and researchers

Endnotes

2018 Edelman Trust Barometer, Global Report; M. Egan, G. Matvos, and A. Seru, "The Market for Financial Adviser Misconduct," NBER Working Paper No. 22050, February 2016.

E. Fama, "Agency Problems and the Theory of the Firm," Journal of Political Economy, 88(2), 1980, pp. 288–307; E. Fama and M. Jensen, "Agency Problems and Residual Claims," the Journal of Law and Economics, 26(2), 1983, pp. 327–49.