Do Government Grants to Charities Crowd Private Donations Out or In?

The basic hypothesis of crowding out is simple: Suppose individuals care only about their own private consumption and the charity's capacity to spend. In particular, they are indifferent to whether their own gift is voluntary or is involuntarily paid through taxes. As a result, any effort by policymakers to support this charity through more involuntary taxes would be met with equal reductions of voluntary gifts as donors work to reestablish their optimal total contributions. The net effect is that the government support for the charity completely crowds out private giving.

When confronted with more realistic theory, the basic hypothesis of crowding out quickly falls apart. First, complete crowding requires that donors be "pure altruists," that is, they engage in consequentialist reasoning.1 If individuals have other motives for giving, such as private benefits of a "warm glow," or social motives like image or pride, then complete crowd-out may not hold.2 Notice too that without impurely altruistic motives for giving there is also little use for fundraisers. Yet charities have very sophisticated and active fundraising operations. This leads us to questions such as: How does fundraising attract donations? What are the objectives of fundraisers? How do government grants affect both donors and fundraisers?

To examine these questions empirically, we first need to observe how donors respond to changes in government grants to the charities they support. In doing so, we must recognize an important source of bias. If there is a natural disaster, for example, then both the donors and the government will want to give more money for the Red Cross. This will make it appear that donations and grants to the Red Cross are positively correlated, thus biasing estimates toward crowding in.

In an important and early paper that recognized this bias, Abigail Payne estimated crowding out of about 50 percent; private charitable giving to an organization fell by about half the amount of government transfers to it.3 Her paper, like the previous literature, did not treat charities as active participants in the market for donations. My recent empirical work on crowding out, much of it done jointly with Payne, aims to look directly at the mechanism of crowding out. We do this by including charities as strategic players in a game with donors and the government.

Strategic Charities

One key question related to the link between receipt of a government grant and a charity's total resources is how the charity's fundraising activities will respond. In particular, are charitable fundraisers net revenue maximizers? It is useful here to follow the distinction that non-profits make between continuing campaigns and capital campaigns.

The goal of continuing campaigns is typically to raise enough money to continue meeting the ongoing needs of the charity. This means that most charities will set a funding goal for the year and, roughly speaking, stop raising money when the goal is reached. Managers of such charities are said to be satisficers rather than maximizers. The consequence of this is that charities will stop actively raising money even though the marginal return of the last dollar of fundraising effort is still greater than a dollar.4 Moreover, a common measure of the quality of a charity used by watchdog groups like Charity Navigator is "fundraising efficiency," defined as the fundraising expenses divided by total contributions. This may further discourage charitable organizations from pursuing revenue maximization.

Capital campaigns, by contrast, are typically about expanding the size or scope of the charity. They often involve significant fixed costs, such as new buildings or offices, and may create situations where the managers, and some donors, have more information than others about the quality of the planned expansions. It is difficult for the charity or an informed donor to credibly convey this quality, as both have an incentive to mislead others to believe the charity's quality is high.

If no single donor can pay all the fixed costs associated with the capital campaign, then there is always a zero-equilibrium in which no one contributes. Interestingly, a rule of thumb for fundraising in a capital campaign is to raise about 30 percent of the ultimate goal from a handful of large donors before even announcing the campaign. By coordinating gifts among a limited number of large donors — typically called "leadership givers" — fundraisers can provide the assurance that the fixed costs will be met, and thus eliminate the zero-equilibrium. Moreover, a government grant — often called a "seed grant" — can double as a leadership gift. These large gifts and grants can rule out the zero-equilibrium. The effect could be either to crowd out or crowd in private donations, depending on the scale of the capital investment.5 Leadership givers can also signal information about the quality of a charity. A leadership giver can provide a credible signal of high quality by giving a sufficiently large gift. Winning a government grant can have the same effect.6

New Estimates of Crowding Out

Payne and I have explored the strategic role of charities in several ways. First, we ask whether government grants crowd out giving directly, or work indirectly by causing a reduction in fundraising.7 We focus our analysis on social services organizations and arts organizations. Social services rely heavily on government grants, while the arts do not. We demonstrate that increases in government funding significantly decrease fundraising efforts, especially for organizations that rely on grants more heavily.

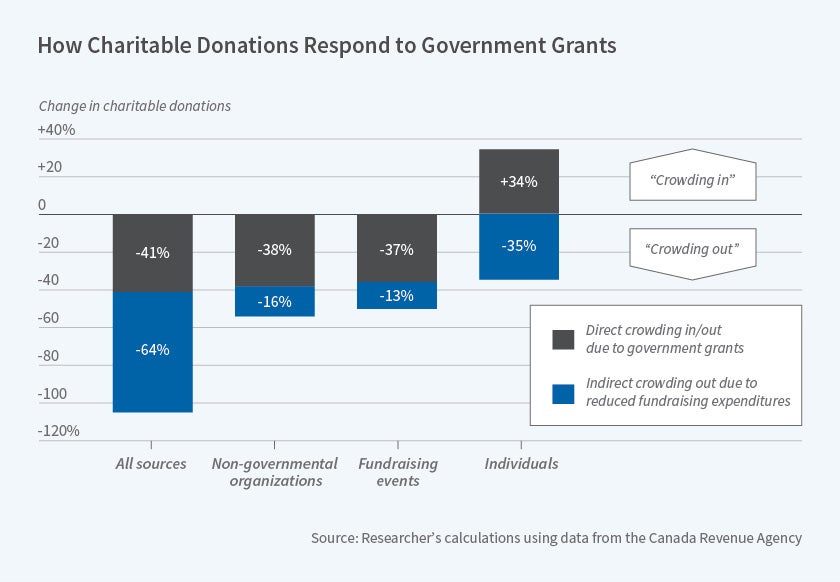

In a second study, we analyze data on more than 8,000 charities operating in the United States.8 We measure an overall level of crowding out of about 75 percent: private donations fall by about three quarters of the amount of government grants. The bulk of the crowding out, 70 percent, is due to a change in fundraising. In fact, donors may be crowded in, as predicted by the informational role of grants as signals of quality. In a related study, we analyze more than 13,000 Canadian charities over more than 15 years.9 In this dataset, we are able to measure whether individuals gave directly, or through participation in fundraising events such as gala dinners. The results are reported in Figure 1. For overall private giving, we measure crowding out of close to 100 percent of government grant amounts. Similar to our study using U.S. data, 64 percent of this crowding out is attributable to changes in fundraising efforts of charities. However, the Canadian data reveal a surprising new finding: Individuals who give directly are crowded in by government grants, not crowded out. This is consistent with government funding being a signal of quality. Crowding out of individual giving is entirely attributable to a decline in revenues from fundraising events.

Finally, in joint research with Sarah Smith, we study the UK lottery grant program.10 The UK requires that 28 percent of all revenues of the National Lottery be set aside for distribution to UK charities. Eighty percent of all the money available is distributed through a program called Grants for Large Projects. Large projects are those requiring over £60,000 (about $90,000 at the time). We analyze over 5,000 applications to this program made between 2002 and 2005. Importantly, all applications are reviewed by a panel of citizens who first assign a score to each qualified applicant. The panel then meets publicly to discuss the proposals and select the grant recipients. Our data include cases where two charities have similar scores, but the charity with the inferior score receives the grant while the other does not.

We use a difference-in-differences approach to identify the effect of grant funding on donations to the charity, in which we compare the change in donations before and after the funding decision across successful and unsuccessful charities. We find that receiving a grant has a positive and significant effect on a charity's total income. In other words, these grants do not completely crowd out other funding sources. Indeed, the data again point to crowding in. We then analyze the effects separately for different-sized charities. We find smaller charities, those with incomes less than £1 million per year, show the strongest evidence of crowding in. Moreover, the positive effect of a grant persists well beyond the year of the award. Finally, we observe that grant applications typically request funds for distinct, well-defined activities that extend the current mission of the charity. This is consistent with the idea that seed funding can crowd in other income.

Figure 1

Is Fundraising Making Us Worse Off?

Inherent in many studies of fundraising is an often-unstated premise that more funds raised means a better society. A revealed preference argument supports this: If donors were not made better off by giving, then they wouldn't give. But this ignores an important social aspect of fundraising: Individuals rarely give without having been asked first. Fundraisers often refer to this as the power of asking — asking is often a powerful percipient of a gift. What does this mean for the behavior of both charities and donors?

One can imagine two ways of framing this question. First, people like to give. Being asked simply reduces the transaction costs, making it easier to realize the joy of giving. Second, in a more subtle analysis, people with big hearts must exert self-control on their giving. There are far too many good causes in the world than a single person could possibly give to, meaning lines must be drawn somewhere. Then the question becomes: Can people stick within these lines, even if they are directly asked to give? Or, will they find more giving too tempting? A clever self-control strategy for such a donor is simply to avoid being asked — if the charity will let them.

A recent field experiment explored these questions by using the familiar Salvation Army Red Kettle campaigns. The Salvation Army allowed Hanna Trachtman, Justin Rao, and me to place bell ringers experimentally at one of the two main entrances of a suburban grocery store, making them easy to avoid, or at both entrances, making avoidance difficult. The bell ringers were either silent as people passed (although the ringing bells clearly signaled their receptivity to a gift), or simply said to those who passed by, "Please give today."11 When the bell ringers were silent, and only one door covered, we found no effect on traffic in and out of the store. When the bell ringers asked shoppers to please give today, however, traffic through the other door rose by 30 percent. When both doors were covered, the verbal ask nearly doubled giving. This means that those avoiding the bell ringers were not avoiding saying no, but rather were avoiding saying yes and giving. This is an important distinction. It suggests that the fundraisers in this case were causing people to give by making a social interaction with them difficult to avoid.

Another way to see the givers' dilemma is that they face contradictory desires: a temptation to say yes to a fundraiser, and a personal preference to avoid actual giving. This opens a new strategy for fundraisers to exploit: Ask people to decide now to give later. If maintaining social image is more tempting than saving money, even a very short delay in paying for the gift could have significant effects.

Marta Serra-Garcia and I explored this question in a lab experiment.12 We found that asking people now to commit to make a donation within one week resulted in a 50 percent increase in donations over asking for a gift today. This provides support for time-inconsistent preferences as described above. With a series of follow-up experiments, we learned more about the tension underlying individual behavior, focusing on the internal struggle between appearing generous to others and watching one's own budget. This finding raises deep and interesting questions about the welfare consequences of fundraising and more generally of a shift away from government, and toward private charities, as a means of solving social problems.

Endnotes

J. Andreoni, D. Aydin, B. Barton, D. Bernheim, and J. Naecker, "When Fair Isn't Fair: Understanding Choice Reversals Involving Social Preferences," NBER Working Paper No. 25257, November 2018, and forthcoming in the Journal of Political Economy, shows that non-consequentialism in social preferences is essential.

J. Andreoni, "Impure Altruism and Donations to Public Goods: A Theory of Warm-Glow Giving," The Economic Journal, 100(401), 1990, pp. 464–77. The term "warm-glow" is slightly pejorative. The intent is to remind readers that, although the reduced form may help answer many questions, there is still much to learn by unlocking the ways warm-glow comes about. See also J. Andreoni, "Giving with Impure Altruism: Applications to Charity and Ricardian Equivalence," Journal of Political Economy, 97(6), 1989, pp. 1447–58. On social-image in unselfish behavior, see J. Andreoni and B.D. Bernheim, "Social Image and the 50–50 Norm: A Theoretical and Experimental Analysis of Audience Effects," Econometrica 77(5), 2009, pp.1607–36.

A. Payne, "Does the Government Crowd Out Private Donations? New Evidence From a Sample of Non-Profit Firms," Journal of Public Economics, 69(3), 1998, pp. 323–45.

This conclusion can also be reached by invoking the non-distribution constraint imposed on non-profits: Charity managers are accepting as part of their compensation the personal satisfaction of doing good works, not simply engaging in onerous fundraising. Another way to motivate fundraising is to assume that charities vary qualitatively — two disaster relief organizations can be imperfect substitutes if one provides mostly food aid while the other specializes in medical aid. Suppose donors differ by how much they favor food over medical aid. If both charities approach a donor, the donor will give to the charity that represents her preferences best. If only one charity calls to ask for a donation, then the donor will give, but will give less the further the charity is from the donor's ideal quality. Thus, charities setting fundraising expenditures face both extensive and intensive motivations for seeking donations. This model is developed in J. Andreoni and A. Payne, "Do Government Grants to Private Charities Crowd Out Giving or Fund-raising?" American Economic Review, 93(3), 2003, pp. 792–812.

This result is due to J. Andreoni, "Toward a Theory of Charitable Fund-raising," Journal of Political Economy, 106(6), 1998, pp. 1186–213. The theory was tested and confirmed in a field experiment by J. List and D. Lucking-Reiley, "The Effects of Seed Money and Refunds on Charitable Giving: Experimental Evidence from a University Capital Campaign," Journal of Political Economy, 110(1), 2002, pp. 215–33.

J. Andreoni, "Leadership Giving in Charitable Fund-Raising," Journal of Public Economic Theory, 8(1), 2006, pp. 1–22. For a related model, see L. Vesterlund, "The Informational Value of Sequential Fundraising," Journal of Public Economics, 87(3-4), 2003, pp. 627–57, and tests of these ideas by A. Bracha, M. Menietti, and L. Vesterlund, "Seeds to Succeed: Sequential Giving to Public Projects," Journal of Public Economics, 95(5-6), 2011, pp. 416–27.

J. Andreoni and A. Payne, "Is Crowding Out Due Entirely to Fundraising? Evidence From a Panel of Charities," NBER Working Paper No. 16372, September 2010, and Journal of Public Economics, 95(5–6), 2011, pp. 334–43.

J. Andreoni and A. Payne, "Crowding-Out Charitable Contributions in Canada: New Knowledge From the North," NBER Working Paper No. 17635, December 2011.

J. Andreoni, A. Payne, and S. Smith, "Do Grants to Charities Crowd Out Other Income? Evidence from the UK," NBER Working Paper No. 18998, April 2013, and Journal of Public Economics, 114, 2014, pp. 75–86.

J. Andreoni, J. Rao, and H. Trachtman, "Avoiding the Ask: A Field Experiment on Altruism, Empathy, and Charitable Giving," NBER Working Paper No. 17648, December 2011, and Journal of Political Economy 125(3), 2017, pp. 625–53.

J. Andreoni and M. Serra-Garcia, "Time-Inconsistent Charitable Giving," NBER Working Paper No. 22824, November 2016.