Colleges Vary Widely in Promoting Upward Mobility

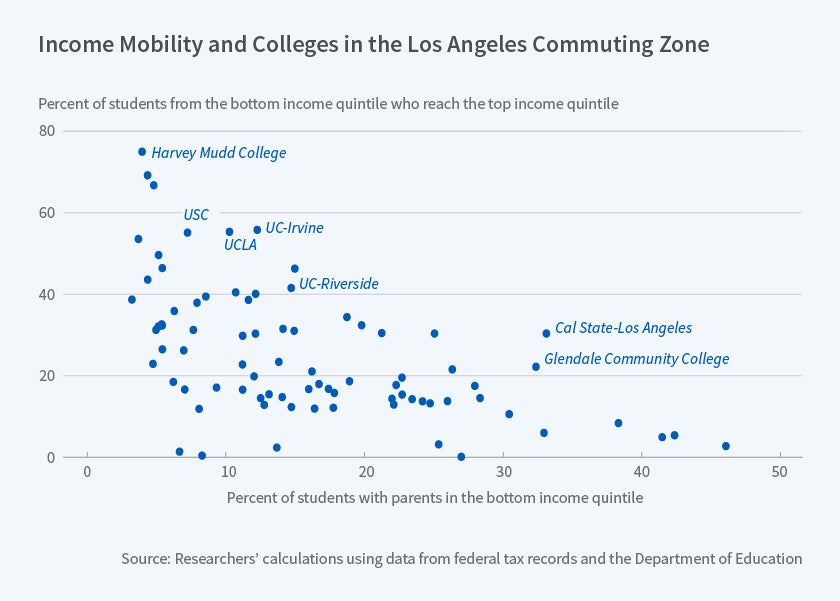

Mid-tier public institutions are most likely to enroll low-income students and successfully prepare them for high-earning careers.

In Mobility Report Cards: The Role of Colleges in Inter-generational Mobility (NBER Working Paper No. 23618), Raj Chetty, John N. Friedman, Emmanuel Saez, Nicholas Turner, and Danny Yagan explore the differences across colleges in the extent to which they advance the economic fortunes of students from low-income backgrounds. They find that, on average, students from affluent and disadvantaged backgrounds at a given college experience similar post-college earnings outcomes. Colleges vary widely, however, in their admission of low-income students.

"[T]he degree of income segregation across colleges is comparable to the degree of income segregation across neighborhoods in the average American city," the researchers report. "These findings challenge the common perception that colleges foster greater interaction between children from diverse socioeconomic backgrounds than the environments in which they grow up."

The researchers calculate a measure for each college that they call its mobility rate, defined as the product of the percentage of students at the college who are drawn from the lowest quintile of income distribution and the percentage of those students who went on to careers that placed them in the top quintile of the distribution. The mobility rate represents the fraction of a school's entire student body who are bottom-to-top success stories, in that they come from low-income parents and make it into the top of the income distribution. Many of the colleges receiving the highest scores are mid-tier public institutions, including many campuses of the City University of New York, several California colleges and several campuses of the University of Texas.

Ivy League and other elite colleges have lower mobility rates. While their graduates from low-income backgrounds earn higher incomes, on average, than students from low-income backgrounds who attend less-prestigious schools, students from families in the bottom income quintile make up a relatively small portion of their student bodies.

The researchers analyze data on college attendance from 1999 through 2013. They focus on individuals who were born from 1980 through 1982, track their college experience, and measure their earnings in 2014, when they were between the ages of 32 and 34. As a case study, the paper contrasts Columbia University with the State University of New York at Stony Brook. Five percent of the Columbia students who were tracked came from the bottom quintile. Of these, 61 percent ended up in the top quintile of earners, leading to a bottom-to-top mobility rate of 3.1 percent. Of Stony Brook students tracked, 16.4 percent came from the lowest quintile; of these, 51 percent wound up in the top quintile, resulting in a mobility rate of 8.4 percent.

However, if the measure of success is reaching the top 1 percent of earnings, Columbia is by far the winner: 15 percent of bottom quintile students at Columbia entered that exclusive club, compared with just 2 percent at Stony Brook.

The researchers note that the colleges with the highest mobility rates are not necessarily those with the highest expenditure per student. For example, mean instructional expenditure at the Ivy-plus colleges is $54,000 per student, compared with $8,000 per student at colleges ranked in the top 10 percent by mobility rate. The researchers note that at high-mobility colleges the share of the student population from low-income families declined during the first decade of this century, perhaps because of budget cuts that raised tuition and reduced financial assistance at these schools.

— Steve Maas